By Steve Thornton

Brainard Field may well be the country’s first municipal airport. Located in a former cow pasture in southeast Hartford, Brainard opened in 1921. Among the facility’s claims to fame are visits by some of the early 20th century’s greatest aviators—including Amelia Earhart and Charles Lindbergh—who landed there to great acclaim.

For its first decade, officials limited the airfield’s use primarily to small passenger flights, but in 1933, as the Great Depression tightened its grip on Hartford (and the country), city officials opened Brainard to commercial traffic in order to spur the local economy. This required expanding Brainard’s facilities and replacing the grass airstrip runways with blacktop pavement.

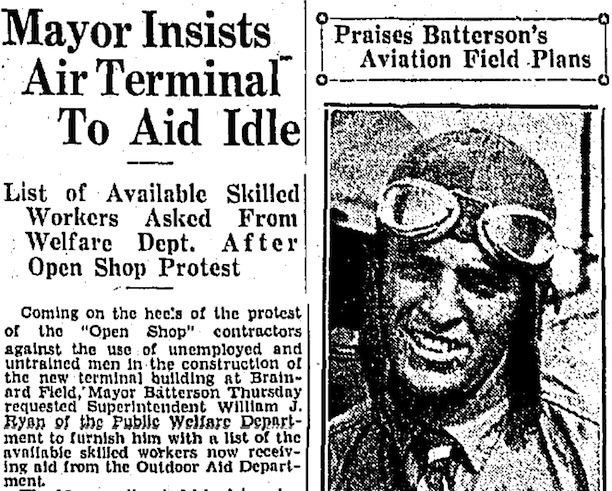

Looking for cheap sources of labor for the project, officials tapped into Hartford’s growing number of jobless. Project organizers hired one hundred workers—mostly family men, desperate for jobs and who previously worked in local factories as machinists, assemblers, laborers, and office clerks until victimized by a period of massive layoffs. Though the men anticipated being paid 40 cents per hour, wages only came in the form of food and partial rent subsidies. (Walter Batterson, mayor of Hartford from 1928 to 1931, suggested that if the men received wages, they would buy alcohol instead of providing for their families.)

Field scene, opening day, Brainard Field, Hartford, June 1921 – Connecticut Historical Society

Labor Pains at Brainard

The jobs were “compulsory,” announced Hartford welfare superintendent William J. Ryan. If any of the men hired for the Brainard project refused to work and then later attempted to apply for public assistance, they faced arrest for nonsupport. This program gave the men “the opportunity to regain their self respect,” Ryan declared, with no apparent irony.

The men had a different view. “I can’t work for nothing,” complained one. “I have to make payments on furniture.” Others spoke of insurance premiums to meet, doctor bills to pay, and kids’ clothing to buy. “Now all we need are a ball and chain,” observed one man.

The day after the project began, as word spread about the lack of available wages, dozens of men threw down their picks and shovels and went on strike. Former railroad man Morris Meaney, and an African American mechanic named Will Thomas, led the organized resistance. They received support from a multiracial committee and quickly met with Mayor Batterson. “We like to feel that no matter how small the wages, we have something to show for our work,” one committeeman told him.

The two sides settled the dispute after the mayor guaranteed not to arrest anyone for refusing the outdoor work. The men agreed to receive $1.00 a day plus food and rent assistance. Two buses from Main and and Gold Streets ultimately transported them to and from the job site each day.

Once assigned to the project, married men without children found themselves restricted to working a maximum of 2 1/2 days a week. Officials allowed men with four or more children to work 5 1/2 days a week. They told workers that if they did not have sufficient food to eat for lunch they should try to get a private charity to assist them.

Federal relief programs were still several years away. The popular theory was to make welfare as difficult to obtain as possible in order to discourage dependence. Handouts violated the American spirit of pride and self-sufficiency, according to policy makers. Most available welfare, as meager as it was, came from local sources.

The Hartford Association of the Unemployed Takes Up the Fight

The Hartford Association of the Unemployed (HAU) was formed in 1932 in response to “conscript labor” such as the original no-pay jobs found at Brainard airport. In addition, the group fought in protest of the scant meals and nutrition options available to those living in Connecticut’s capital.

HAU ultimately established seven chapters in Hartford, including one at Brainard Field. The members initiated free speech rights in order to publicly protest the conditions of poverty in which they lived. During this period, unemployed “hunger marchers” protested outside the Connecticut General Assembly, and thousands of army veterans descended on the nation’s capitol to build on the pressure begun by small efforts such as those initiated at Brainard Field.

Steve Thornton is a retired union organizer who writes for the Shoeleather History Project