By Richard DeLuca

For more than a century before the first heavier-than-air flight of the Wright Brothers in 1903, experiments in the new science of aeronautics focused on various lighter-than-air craft such as the gas-filled balloon, which essentially floated at some great height above the surface of the ground. Despite the air of carnival entertainment that surrounded many balloon ascensions, they were a natural first step in the history of manned flight. These events also exposed both balloonists and the general public to the possibility of human flight.

“A Grand and Pleasing Object”

The first balloon experiment in Connecticut took place in the spring of 1785, when Josiah Meigs, a former tutor at Yale College and the editor of the New Haven Gazette, constructed and flew several unmanned balloons above the town green in New Haven. According to the diary of Yale President Ezra Stiles, the third balloon Meigs sent aloft ascended three times higher than the earlier ones. This balloon is described as having been spherical, 11 feet in diameter, and decorated with the figure of an angel in flight holding a trumpet in one hand and the flag of the United States in the other. Whether by accident or as a result of gunfire from the local militia, the balloon exploded in mid-air, “being converted into a pyramid of Flame at its greatest Height” that became “a grand and pleasing object to the spectators.”

Following the Revolutionary War, balloon enthusiasts, like other inventors, took advantage of the Constitution’s patent law to turn their balloon experiments into money-making ventures. In the summer of 1800, The Connecticut Courant contained an interesting advertisement for ascensions in the “Federal Patented Balloons” of John Graham. Details of Graham’s operation are sketchy, but it appears that he operated with the permission of Moses McFarland, a Massachusetts man who the previous year had received the first federal balloon patent.

Graham balloon ascensions involved a mechanical winch by which Graham controlled the ascension of up to eight passengers in a balloon that was tethered to his machine. Advertisements for the ride noted that “healthy persons may experience pleasure and delight” while those less so “may regain their health by a sudden change of air and atmosphere, and a sudden revulsion of the blood and humors.” The cost of the ascension was nine pence per passenger.

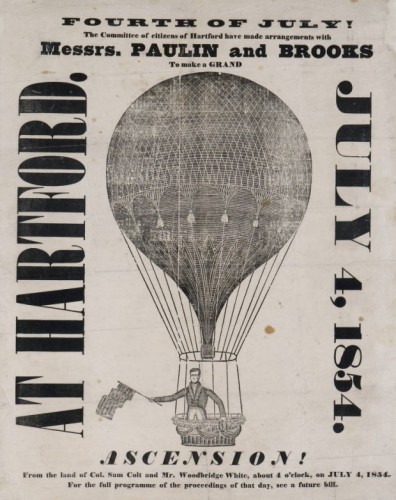

By the 1850s, manned balloon ascensions had become a somewhat common amusement, as aeronauts (as balloonists were called) made untethered ascensions at circus events and Fourth of July celebrations around the country. One of these balloonists, who came to be known far and wide for his ascensions, was Silas Brooks, a Plymouth native who began his career working for Connecticut’s preeminent showman, P.T. Barnum.

From Hoaxer to Aeronaut

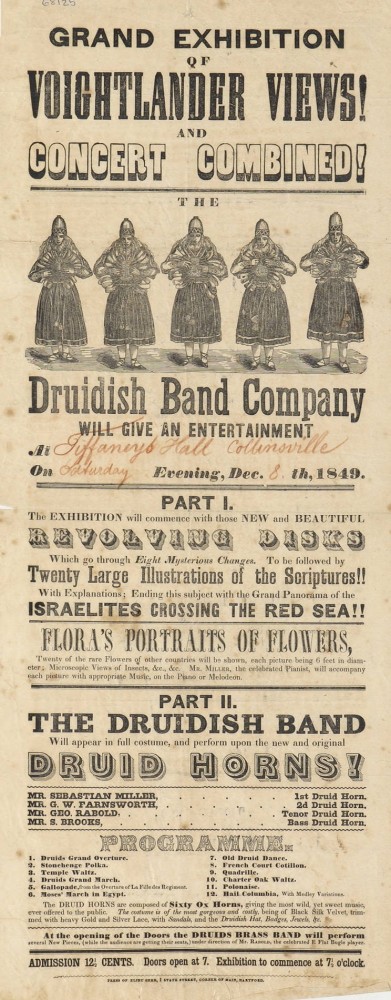

Druidish Band Company advertisement, 1849 – Connecticut Historical Society

Barnum used Brooks to create one of his more popular hoaxes, a band of so-called Druid musicians purported to be dressed in ancient ceremonial garb and playing authentic Druid musical instruments. Brooks fashioned the odd-looking horn-like instruments in a metal shop in Bridgeport. He then trained the five-man band, most of whom were German immigrants who spoke little English, in secret in a hotel room in Bristol.

The band debuted in 1849 and played for months to sell-out crowds at the Barnum’s American Museum in New York City. After touring with the band for several years, Brooks found his true calling. He formed a circus troupe in Cleveland that included aeronaut and balloon ascension as part of each performance. When his balloonist took ill one day, Brooks made the ascension in his place and never looked back.

During a career that spanned 40 years as an aeronaut, Brooks made nearly 200 balloon ascensions, many in his home state of Connecticut. At one event held at Cherry Hill Park in Collinsville on July 4, 1884, Brooks filled his balloon with hydrogen gas manufactured on the premises “in one of the greatest experiments ever witnessed.” He did this by combining in large vats 5,000 gallons of water, 2,400 pounds of sulfuric acid, and 2,000 pounds of iron turnings. With a keen sense of the public’s endless appetite for carnival stunts, Brooks took with him on that flight a small dog wearing a parachute—and then dropped the dog from the balloon at a height of several thousand feet.

Brooks made his last balloon ascension on July 4, 1894, at Bushnell Park in Hartford, but his airborne career ended on a discouraging note. No sooner had he begun the ascension when his balloon careened off nearby buildings and got tangled in the trees. Despite having made a good living as an aeronaut, Brooks died a pauper in 1906, three years after the first flight of the Wright Brothers. He is buried in Burlington, Connecticut.

Richard DeLuca is the author of Post Roads & Iron Horses: Transportation in Connecticut From Colonial Times to the Age of Steam, published by Wesleyan University Press, 2011.