By Briann Greenfield and David Corrigan for Connecticut Explored

From the colonial period into the early 19th century, Connecticut’s foreign trade consisted of exporting lumber, livestock, and agricultural products destined almost entirely for the West Indies. Later, in the state’s industrial infancy, Connecticut-made products such as clocks, brass buckets, coffee mills, buttons, and a host of other so-called “Yankee notions” were consumed domestically, carried by Connecticut-based peddlers north and south along their routes and sold to customers in towns from Maine to Arkansas.

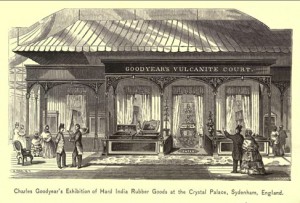

Goodyear’s exhibit at the Crystal Palace Exhibition, London, 1851 from Trials of an Inventor: Life and Discoveries of Charles Goodyear by Bradford K. Pierce

Connecticut Goods Go Abroad

Bristol clockmaker Chauncey Jerome, in his autobiographical History of the American Clock Business (F.C. Dayton, New Haven, 1860) reported that Connecticut manufacturers, like those in other states, had been able to sell their products only domestically because European merchants were prejudiced against all American-made goods. Jerome had almost single-handedly dismantled this prejudice when, in 1842, he sent the first shipment of his low-priced one-day brass clocks to England. The British customs agents questioned the shipment’s declared value, disbelieving that the clocks could possibly be made and sold for the low price of $1.50, but they ultimately allowed the goods to enter the country. Jerome boasted in 1860 that he had penetrated not only the British market but other markets across the globe, as millions of his clocks had been exported to Europe, Asia, South America, Australia, Palestine, Egypt, Jerusalem, the Sandwich Islands (now Hawaii), “and, in fact, to every part of the world.”

In 1851 Samuel Colt introduced another quintessential Connecticut product to Great Britain with a display of his patented repeating firearms at the famous Crystal Palace Exhibition in London, one of the earliest venues for the exhibition of the industrial, artistic, and agricultural products of many of the world’s nations. Colt set a precedent for Connecticut manufacturers who would show their wares at European expositions and fairs. He also dominated the firearms exhibition, winning over many British critics who were loathe to accept that an American, machine-made firearm could outperform a similar weapon manufactured according to the long-entrenched British guild system, under which all the parts of each single weapon were made and assembled by a single craftsman.

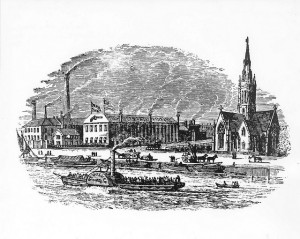

Samuel Colt’s London factory on the banks of the Thames River, London, 1853 – Connecticut State Library,State Archives, PG 460, Colt Patent Fire Arms Manufacturing Company

Colt also understood the value of word-of-mouth testimonials in creating an international market for his firearms. Throughout the 1850s, he presented elaborately cased and engraved samples to many foreign military and political leaders, most of whom likely had never encountered an American-made product before. Recipients included General José Rufino Echenique, the president of Peru, Benito Juárez, president of Mexico, Saʿīd Pasha, viceroy of India, and S.P. Pawarendrramesr, the second king of Siam. Colt also recognized the importance of winning the gold medals awarded at American and international fairs and expositions, noting that “These medals we must get and I must have them with me in Europe to help make up the reputation of my arms…these things go a great ways in Europe.”

Partly as a result of his success at the Crystal Palace, Colt was spurred to establish a London factory in 1851, sending both workers and machines from Hartford to ensure that the London-made firearms would conform to his production and quality standards. Colt’s London factory appears to be the first overseas factory established by a 19th-century American manufacturer.

Companies in Bridgeport, Canton, and Elsewhere in State Tap International Markets

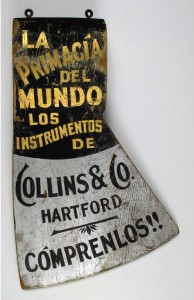

Wooden trade sign, Collins Co., Hartford, late 19th century – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Online

The Collins Company was also a pioneer in the foreign trade. As early as the 1840s, Hartford shipping merchants began to include Collins axes in cargoes bound for plantations in the West Indies that were worked with enslaved labor. Collins soon developed machetes and specialty edge tools, many adapted from workers’ own designs, for use on sugar, cocoa, coffee, and other plantations throughout Latin America and the Caribbean both before and after the abolition of slavery. With an extensive line of agricultural and forestry tools, Collins found ready buyers in South America, North America, Africa, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. But success brought imitation and thus unfair competition. An 1881 Hartford Daily Courant article detailed the company’s efforts to enforce international treaties and protect its trademark from English and German counterfeiters.

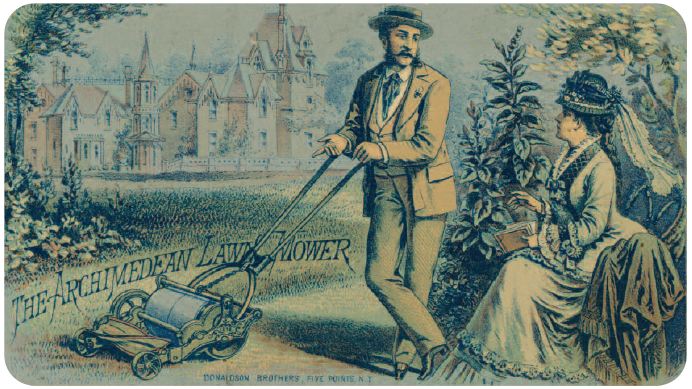

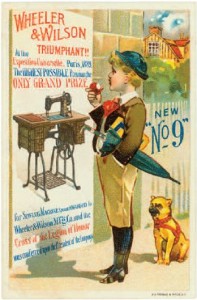

Declining shipping costs and the construction of the first transatlantic telegraph cable in 1851 prompted more Connecticut companies to pursue markets overseas. By 1867 the Wheeler and Wilson Mfg. Co. of Bridgeport was exporting sewing machines to Russia. And the Archimedean Lawn Mower Co. of Hartford described its product in an 1870s trade card as “The most beautiful and perfect Lawn Mower in the world. It stands to-day at the head of the list of Lawn Mowers in the United States and Europe.”

Connecticut Wares Displayed at World Expositions and Fairs

Trade card for Wheeler & Wilson Mfg. Co., Bridgeport, ca. 1890 – Museum of Connecticut History

Connecticut manufacturers continued to display their products at the expositions and fairs held in Europe and around the world in the 19th century. 1878 saw more than 25 Connecticut manufacturers, representing 13 cities and towns, showing their products in 21 different classes at the Exposition Universelle in Paris. In the mining and metallurgy section, which included hardware and other metal products, there were more exhibitors —including Russell & Erwin of New Britain, Mallory & Wheeler of New Haven, and Yale Lock Co. of Stamford—from Connecticut than from any other state. Leather power transmission belts by The Underwood Belting Co. of Tolland were used in the Exposition’s machinery hall.

By the end of the 19th century, many Connecticut manufacturers, in addition to exhibiting at expositions around the world, turned their eyes and interest toward the emerging markets in Central America and South America. Many opened sales offices in countries there, and some, such as P. & F. Corbin of New Britain, began printing full product line catalogues in Spanish.

Selling products abroad opened new markets for 19th-century Connecticut manufacturers and began the transformation of American small business into the large, multinational corporations that we know today.

Briann Greenfield is associate professor of history at Central Connecticut State University. David Corrigan is curator of the Museum of Connecticut History. Both are members of the Connecticut Explored editorial team and frequent contributors to the magazine.

© Connecticut Explored. All rights reserved. This article originally appeared in Connecticut Explored (formerly Hog River Journal) Vol.10/ No. 1, Winter 2011/2012.

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.