By Steve Thornton

In 1955, the most racially integrated public space in Connecticut may have been the rock and roll concerts at Hartford’s State Theater. Despite widespread discrimination against African Americans in jobs, housing, and schools, black and white kids came together here on common ground. Located at the intersection of Main, Morgan, and Village Streets, the State Theater featured a new musical genre that both revolutionized American culture and played a lesser-known, but significant role in the fight for racial justice.

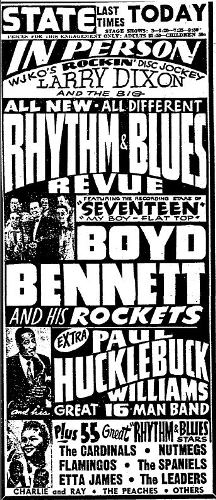

The first rock and roll performers to appear in Hartford were the Penguins, a black doo–wop quartet whose biggest hit, “Earth Angel,” had just reached the Billboard charts. The song was an early “cross-over” hit; its popularity breaking the barrier between black and white radio audiences. Bo Diddley, Etta James, Fats Domino, Frankie Lyman and the Teenagers, and dozens of other performers followed at the State, all with white acts such as Bill Haley and His Comets, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Buddy Holly on the same billing.

Racial Tensions on the Rise in 1955

Racial turmoil swelled that year; it was in 1955 that two white men lynched fourteen-year-old Emmett Till in Mississippi. It was also in 1955 that authorities arrested Rosa Parks in Montgomery, Alabama, sparking the famous bus boycott. On August 1, 1955, the Georgia Board of Education fired all teachers who held membership in the NAACP.

During this same period, the Connecticut state civil rights commission reported that it was “virtually impossible for a Negro to rent a home in a white neighborhood.” The state’s NAACP targeted banks that refused to grant housing loans to black families. Literacy tests for voting were still part of state law. Two skilled electricians, both African Americans, struggled for five years to join an all-white union in order to work at their trade. According to one poll, only 20 percent of Connecticut’s white population supported full integration of the races.

It was remarkable, then, that the local press did not identify black rock and rollers who came to town by their race. Instead, they described them by their particular musical style—both in paid advertisements and in concert reviews. In almost every other case, newspapers of that time labeled African American individuals as “colored” or “Negro,” especially when reporting a crime.

That is not to say Connecticut’s white majority was happy with early rock music. Racist press commentary was frequent, using not-too-subtle code words. Rock and roll was “jungle stuff” wrote one local critic. It was “cannibalistic” and “tribalistic” according to Dr. Francis Braceland, head of Hartford’s exclusive Institute for Living.

The first official crackdown on rock and roll took place on March 19, 1955. Police halted a New Haven festival “when it seemed the dancers were getting out of hand.” Concert goers were all over 21 and vendors legally sold beer, but it was the “uninhibited” and “touchy” dancing that really seemed to disturb the authorities. “There will be no more of that,” stated Chief Francis McManus. Bridgeport then banned all rock events, three of which promoters already scheduled for April. In contrast to these crackdowns, when Hartford’s police chief suggested banning rock and roll (after eight arrests at a concert for fighting) Councilman James Kinsella strongly denounced the proposal as “censorship.”

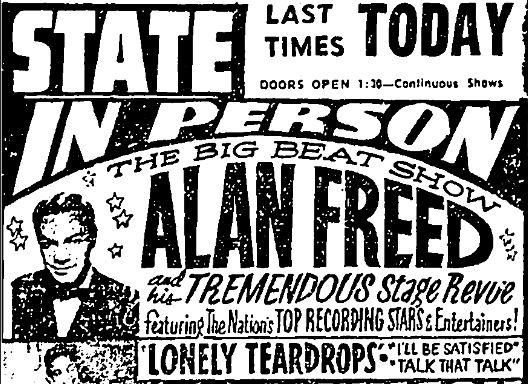

Alan Freed Helps Integrate Rock and Roll Audiences

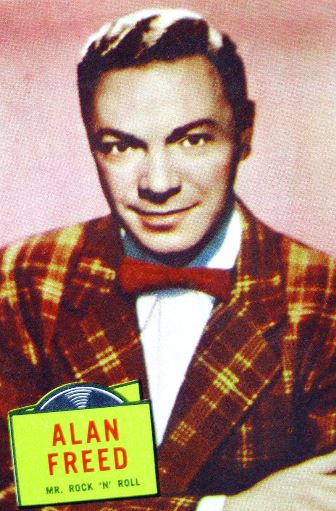

One man, more than any other, proved responsible for the integration of rock and roll audiences in Connecticut. Alan Freed, a Cleveland disc jockey, first played Rhythm & Blues (R & B, or “race music”) in 1951. Until that time, the music remained largely in the black community. Freed earned national attention for a huge integrated concert in New York just a few months before the first Hartford event. He was in Hartford frequently, acting as master of ceremonies at every concert he produced. “Mr. Rock and Roll” became as popular as the groups he promoted.

Many also credit Freed for coining the term “rock and roll.” While some critics called the music “noise,” Freed understood the historic roots of rock. The music “began on the levees and plantations,” he explained. “It took on folk songs and features blues and rhythm. It’s the rhythm that gets to the kids.” The controversial DJ is remembered today for his part in the payola scandal, a pay-for-play scheme with the record companies. But his legacy is really as the pioneer of rock and roll on radio, and his successful efforts to help integrate a new generation of youth.

The State Theater closed its doors in 1960 and workers demolished it two years later. Alan Freed died in 1965. He was among the first group of inductees—black and white—to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland.

Steve Thornton has been a labor union organizer for 35 years and writes on the history of working people. This article originally appeared on ShoeLeatherHistoryProject.com