By Nicole Sagullo

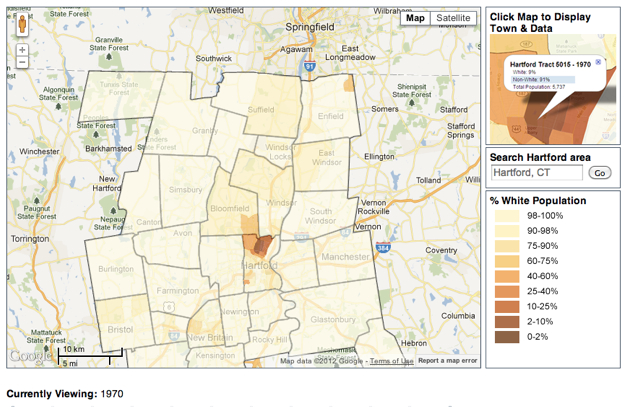

Over the past 50 years in Connecticut and elsewhere, discriminatory real estate practices known as steering and blockbusting have played a prominent role in creating racial segregation in housing. The impact of such once legal practices on the racial composition of the greater Hartford area can be seen in an interactive map documenting racial change in the region from 1900 to 2010. In the early decades of the 20th century, data shows a small, non-white population isolated in the city center of Hartford. Over the years, as migrants from the South and elsewhere came to the state, this population grew and a variety of factors determined where newcomers could settle.

Racial Change Map displaying the Non-White Population in 2010, Racial Change in the Hartford Region, 1900-2010 – University of Connecticut Libraries, Map and Geographic Information Center (MAGIC)

Of particular interest to those studying demographic patterns is the growth of the non-white population in Bloomfield beginning in the late 1960s. The percentage of residents classified as “non-white” grew as minorities relocated from Hartford to this nearby town and whites moved out. Research by The Cities, Suburbs and Schools Project, a collaborative effort involving Trinity faculty and students as well as community members, shows that the composition of the area was affected by several factors, including real estate practices employed during this time—and that these practices influenced how the community and others near it continued to take shape.

Blockbusting: An Illustration

Blockbusting is the term used to describe the practice of encouraging existing homeowners living in primarily white neighborhoods to sell their properties to a real estate agent at below market value. Disreputable real estate agents would scare white residents, claiming that integration would lead to decreased property values; this tactic led to “panic selling.” In turn, the agent would sell the home above market value to black home buyers. Blockbusting allowed agents to maximize profit by buying low and selling high. They targeted the small supply of homes where blacks could live without being harassed or excluded by then-legal covenants or other deed restrictions.

Bloomfield Chamber of Commerce President Raymond McMahon, & Mayor Edward J. Stockton with greeting sign, 1971 – Hartford Times Collection, Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

Blockbusting practices helped determine Bloomfield’s racial composition throughout the late 1960s and ‘70s. For example, as reported in the Hartford Courant on February 24, 1974, a white resident of Bloomfield recounted receiving calls from real estate agents urging him to sell his house at a lower rate because, with non-whites moving into the area, property values had supposedly declined. The article further detailed the role of real estate agents in shaping Bloomfield’s demographic makeup.

Racial Steering

Related to blockbusting, racial steering involves real estate agents directing people of certain races to specific areas—and away from others. One white home buyer, for example, reported an agent’s behavior to the Hartford Courant. He explained that the agent praised Avon and West Hartford but, in contrast, spoke negatively about Bloomfield and its school system. The home buyer concluded that the agent may have been afraid to insult clients by taking them to integrated neighborhoods. Historical facts suggest, however, that maintaining racial segregation through such means as restrictive covenants, redlining, and racial steering has been used to influence property values. Such discriminatory and, very often, illegal practices have contributed to racially isolated neighborhoods by perpetuating stereotypes.

Illegal Practices Persist

Racial steering and blockbusting, though illegal, remain present today. An article entitled “Home Buyers Suspect Racial Steering,” which appeared in the Hartford Courant on September 8, 2003, discussed the implications of this practice in the 21st century. Citing the observations of residents in affected neighborhoods as well as statistical data, the article concluded that real estate practices and other forces still encourage patterns of segregation based on skin color. For instance, a former member of the town council in Windsor reported that although a house in his neighborhood went on the market several times it was not, to his knowledge, shown to prospective buyers who were white. As 2000 census data shows, ¼ of the affluent black population of the Greater Hartford area lives in six geographically adjacent census tracts in Bloomfield, Windsor, and the Blue Hills section of Hartford. Further, according to the article, the census numbers indicate that black residents in Hartford’s suburbs “were more racially isolated from white residents in 2000 than they were in 1990.”

The use of blockbusting and racial steering in the 1960s and ‘70s helped start patterns of racial segregation that persist today. And, as more recent evidence suggests, steering practices prevent integration by limiting opportunities available to non-white populations.

Nicole Sagullo, who is working towards her Bachelor’s degree in Psychology and Educational Studies at Trinity College in Hartford, contributed this essay during the 2012-13 academic year.