…that the Hartford Circus Fire may be the worst human-caused disaster ever to have taken place in Connecticut.

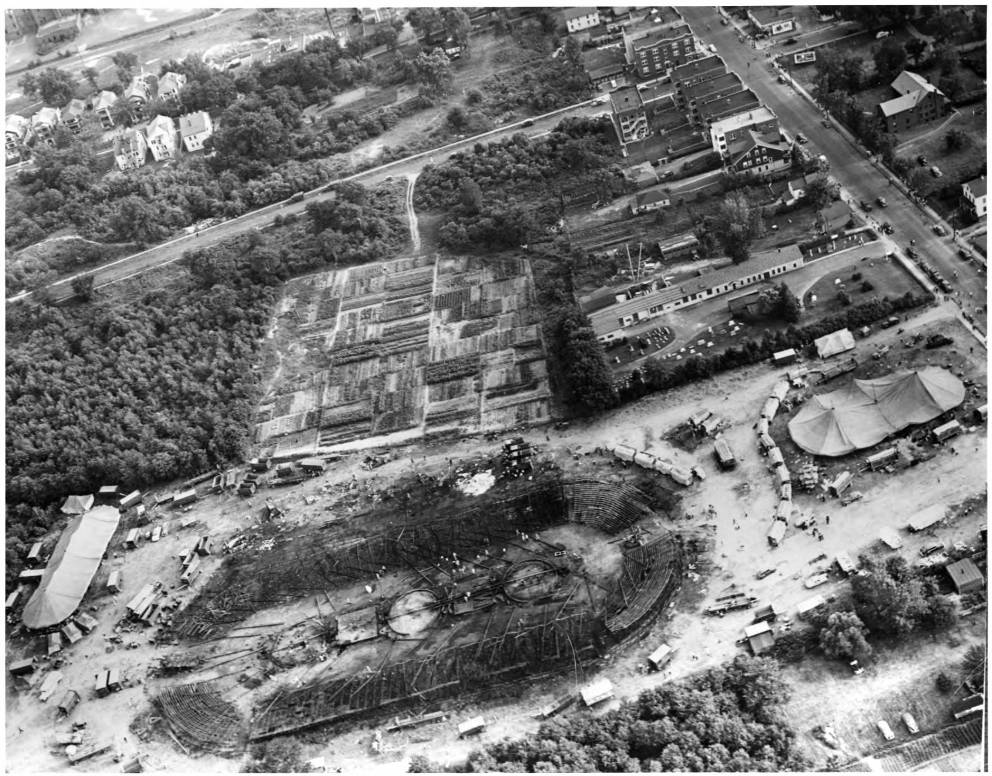

Thursday, July 6, 1944, was hot and humid but a fine day to see the Ringling Brothers Barnum & Bailey Circus in a field on Barbour Street in Hartford. Attendance was estimated at 6,000. A carelessly tossed cigarette butt ignited a canvas partition screening the men’s toilet. The fire spread via a guy rope to the oil-impregnated canvas of the main circus tent. One of the Flying Wallendas pointed to the blaze from his perch and screamed “The tent’s on fire!”

Chaos erupted. Ushers ran with buckets of water toward the flames, yet the fire quickly got out of control. The crowd began running toward the exits as flaming pieces of canvas fell onto their hair and clothing. Some fought their way to the top tier of seats where they leapt 15 feet to the ground or slid down the poles and ropes. Barbara Orsini Surwilo recalled, “My father reacted quickly, [we dropped from the bleachers to the ground and] raced to the back of the tent where he and a few other men sliced the canvas….He handed my sister and I off to a large, elderly black man with huge hands who firmly gripped six or seven children in each hand. My father ran back and into the tent….He said there were about 10 men working as a team [to rescue people.]” In just 10 minutes, 168 died, at least 80 of them children. Survivors included 262 who were seriously burned and 222 with other injuries.

A Catastrophe of Grim Proportions

In the field outside the tent, parents ran frantically to and fro, searching for their children. Rescuers carried bodies, some dead and some alive, and emergency aid was mobilized right away. The Bristol Press reported that neighboring homes had “lines of men, women and children from the sidewalks to the telephone, patiently awaiting their opportunity to convey the good news of their safety.” Governor Raymond E. Baldwin personally directed rescue and relief work and “stayed on the job far into the night.” Additionally, “Scores of soldiers from a nearby army rest camp, sent to the circus for relaxation, forgot their own injuries suffered in action overseas, to aid in numerous rescues.” According to Ellsworth Grant in Connecticut Disasters, “the Colt Armory dispatched four ambulances, four doctors, eight nurses, and 20 guards.”

The aftermath was grim. A Time Magazine article dated July 17, 1944, reported that doctors, dentists, and jewelers were called in to help identify victims by their fillings, scars, rings, and watches. On July 6, 2005, a memorial to the victims of this terrible disaster was dedicated in the park behind Wish School; it features the names of the 168 fatalities.

Contributed by Emma Demar, a Connecticut Explored intern and Trinity College student in 2011, and Elizabeth Normen, the magazine’s publisher.

© Connecticut Explored. All rights reserved. This passage originally appeared as part of the article “What a Disaster!” in Connecticut Explored (formerly Hog River Journal) Vol. 9/ No. 4, Fall 2011.

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.