By Christine Adams

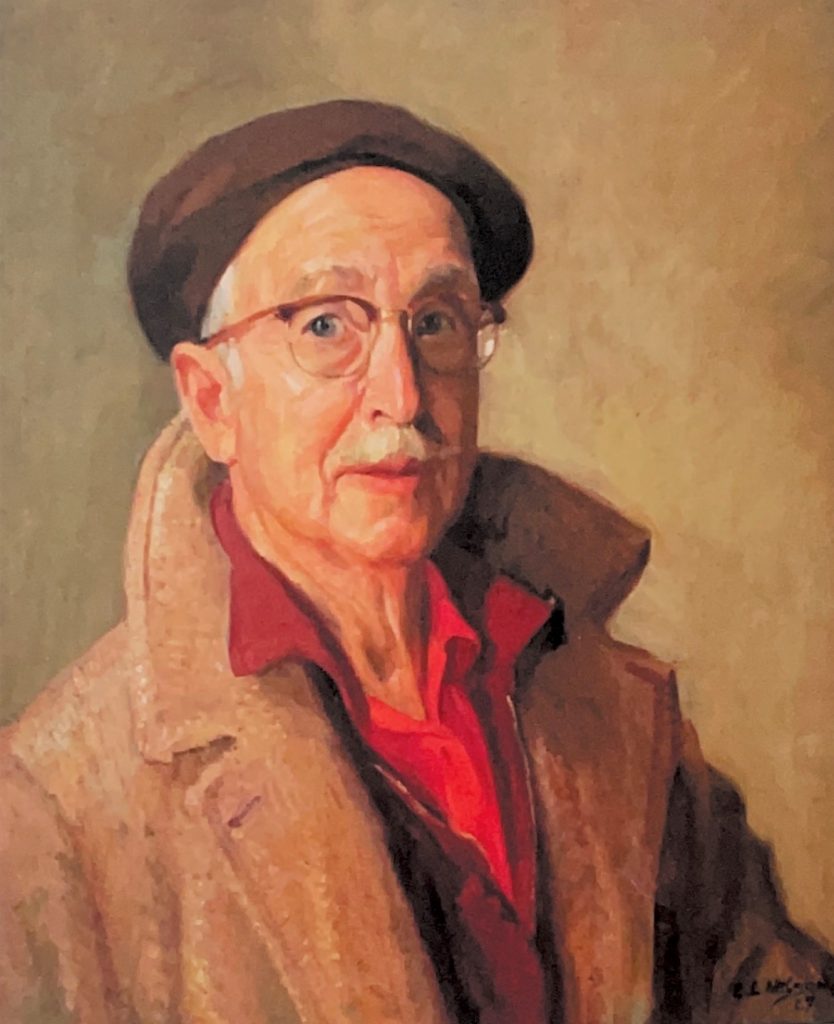

George Laurence Nelson—the artist who bequeathed Seven Hearths to the Kent Historical Society—disagreed sharply with the romantic notion that an artist must suffer in order to create profound art. He stated that “some do suffer, but I don’t think it results in any more creative works. I’m from the school that believes in long training.” As circumstance would have it, Laurence had it all: long training, a genetic predisposition for visual art-making, a strong work ethic, and a healthy human dose of inevitable suffering. In addition to his artistic pursuits, George Laurence Nelson lived in Kent, Connecticut, for over half a century and restored the historic Seven Hearths house.

An Early Start to Art

Born in 1887 to two world-acclaimed artists, Alice Kerr-Nelson and Carl Hirschberg, parental bequest had a significant influence on Laurence’s body of work. Carl studied under Cabael in Paris and was the founder of the Salmagundi Club in New York. Alice was a watercolorist and collaborated on paintings with William Merritt Chase and Charles Yardley Turner.

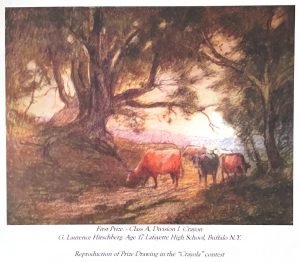

One might say that Laurence was born with a paintbrush—or crayon—in his hand. In fact, at age 17, he won First Prize (Class A, Division 1) in a contest sponsored by the Binney & Smith Company for work he created using Crayola crayons while a student at Lafayette High School in Buffalo, New York. His career began in earnest when the company hired him to illustrate for their national campaign.

(It was shortly after, in 1906, that Laurence and his two brothers, Nelson and Edgar, began to use their mother’s maiden name—Nelson. Some suggested they made the change so as not to be confused with their famous parents. Others theorize it was a result of anti-German sentiment that was growing in the years preceding World War I.)

Painting Family Tragedy

As for suffering, Laurence’s family had more than its share. In August of 1915, while traveling home from Belize where he worked as a mining engineer, Laurence’s older brother, Nelson, was lost at sea during the hurricane that eventually destroyed Galveston, Texas. It was not until late November that a piece of his ship, the S.S. Marowjine, washed up on the shores of Galveston. His father, Carl Hirschberg, then received correspondence from The National Weather Service, the US Secretary of the Navy, Joseph Daniels, and US Senator James Wadsworth expressing sympathy for the family’s tragic loss but also firmly stating that the US government no longer had the resources to search for those lost at sea. (The correspondence resides in the Kent Historical Society’s collections.)

Over a century later, a Kent Historical Society docent, Linda Palmer, serendipitously stumbled upon a seemingly unfinished portrait of Nelson at auction. Her trained eye recognized Laurence’s hand and his brother’s likeness. The story of his demise underscores the portrait’s poignancy: a young, handsome man, under a sheer veil covering his torso, with a juxtaposed white rose. Behind the veil is the bust of Nelson, a shoulder left unpainted and blank, suggesting a life interrupted.

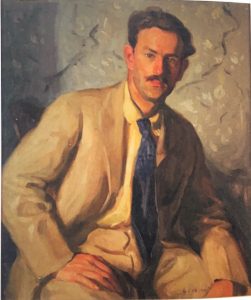

Laurence’s portrait of his brother Edgar, who was diagnosed with epilepsy – Courtesy of Kent Historical Society

Laurence also painted his other brother, Edgar, who was diagnosed with epilepsy at age four. After a series of violent seizures during his teenage years, the family made the difficult decision to admit him to the Craig Colony for Epileptics in Sonya, New York. Edgar remained institutionalized for the rest of his life, but he still managed to earn a degree in botany from Cornell University and become an award-winning woodworker. According to Kent Historical Society curator, Marge Smith, “[Edgar’s] diaries reveal a brilliant, inquisitive mind that allowed him to observe and analyze the rhythms of his seizures in hopes of lessening the stress of their impact.”

Laurence’s Art

Laurence reportedly painted every day of his life beginning at age 11. He took only two weeks off for his honeymoon following his marriage to his wife of 56 years, Helen Redgrave—an art critic for the New York Globe. After the stock market crash of 1929, Laurence and Helen moved to their weekend home in Kent full-time where Laurence supplemented their income by doing conservation and framing work in his second-floor studio, teaching art classes, and even selling ads.

Laurence had superior fundamentals and expert technique, the drive, and the passion to make truly memorable work. His art quite literally inspired kings. (In 1911, Britain’s King George V hired Nelson to paint 64 of his royal ancestors in miniature.) A 1922 review at the Brooks Memorial Art Gallery in Memphis declared his work of “fine technical handling and execution” and marveled about his painting of “a gay basket of peaches turned on its side with the luscious fruit rolling out,” claiming, “You can almost get a cutaneous irritation for the fuzz on the peaches.” Nelson’s ability to convey the human condition through his brush—most notably through the portraits of his loved ones—makes his visual art a truly connective experience.

Christine Adams serves on the Board of Trustees for the Kent Historical Society. A resident of New Preston, she is the author of an anthology of poetry and also works as a researcher for the Gunn Historical Museum.