By Emily Clark

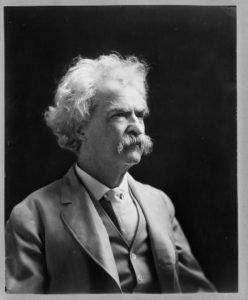

Authors often draw inspiration from those around them when creating characters for their novels, and Connecticut’s most famous author is no exception. While living in his Hartford home, Mark Twain wrote The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, using “good-natured” and “devoted” George Griffin as a likely model for one of literature’s most memorable figures—Jim, the runaway enslaved man. Though this Black man attended the family as a servant for years, he also became a faithful companion and confidant to Twain—who Griffin knew best by his birth name of Samuel Clemens.

From Slavery to Freedom

Born into slavery in the late 1840s, George Griffin faced many obstacles and served many roles before coming to Connecticut. During the Civil War, he worked as a body servant to Union General Charles Devens of Massachusetts. After the war, Griffin moved north toward Hartford. In 1874, he was looking for work and stopped at the Clemens home on Farmington Avenue to wash windows. This fateful decision led him to spend over 17 years as butler and friend to the family.

Life on Farmington Avenue

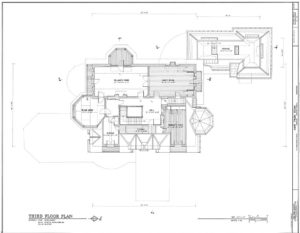

Third floor plan of the Mark Twain House, where George Griffin kept a bedroom – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Griffin’s role as butler to the Clemenses included overseeing the 11,500 square-foot home of 25 rooms on three floors occupied by the author, his wife Olivia, three daughters, numerous pets, and several additional servants. Griffin kept a room on the third floor, allowing him to be close to the family and available for their needs. Over time, he took on much more than organizing the household. Clemens called him a “peace-maker in the kitchen,” one who “adjusted disputes in that quarter before they reached the quarrel-point.” This butler, however, also became a legal and literary adviser to the author as well as his billiards partner for late night games. As a playroom companion to young Susy, Clara, and Jean, Griffin maintained a personal relationship with all members of the household. Even after he and his wife, Mary, purchased their own home in Hartford, he continued to keep his private third-floor bedroom on Farmington Avenue.

In an unpublished manuscript, Clemens referred to Griffin as “wise, polite, always good-natured, cheerful to gaiety, honest, religious, a cautious truth-speaker, devoted friend to the family.” He remembered him as being “shrewd” in making money—often as a betting man during Hartford’s horse-racing season—but also very generous as he would offer loans to those in the Black community where he served as deacon in Hartford’s Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church.

A Literary Inspiration

It was while Griffin worked for and lived with the Clemens family from 1875 to 1891 that Clemens—writing under the pen name of Mark Twain—published two of his most acclaimed novels—The Adventures of Tom Sawyer in 1876 and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in 1885. Because of Griffin’s closeness with the family and the attributes he possessed, critics have said that he may have been the inspiration for Jim, the runaway enslaved man in Huck Finn whom the title character befriends.

That closeness was evident outside the Hartford home as well. Together on a visit to New York, Clemens noted an uncomfortable reaction from some people as the men of two different races walked into a publisher’s office. “A white man and a negro walking together was a new spectacle to them,” Clemens wrote of this experience in the 1890s, “The glance embarrassed George but not me, for the companionship was proper; in some ways, he was my equal, in some others my superior.”

When the Clemens family moved to Europe and Griffin headed to New York in search of work, the author continued to hold a fondness for his former companion and servant. When Griffin died in 1897, Clemens eulogized him in correspondence with a friend, saying, “George is gone…our friends are passing one by one; our house where such warm blood and such dear blood flowed so freely, is become a cemetery. But…their life made it beautiful…We shall have them with us always and there will be no parting.” Though no photographs of George Griffin exist, the legacy of his work and friendship persist, recorded in detail by one of Connecticut’s most famous authors.

Emily Clark is a freelance writer and an English and Journalism teacher at Amity Regional High School in Woodbridge.