By Elaina Rollins

Hartford lawyer and Democratic delegate Simon Bernstein stuck out from his political peers at the 1965 Connecticut Constitutional Convention. While the Democratic and Republican chairmen of the time were entrenched in a debate over the state’s unequal political representation system, Bernstein dared to dream a little bigger. As a member of the Bloomfield Board of Education, Bernstein recognized that Connecticut was the only state that did not guarantee its citizens a constitutional right to an education. Bernstein thus decided to draft a new amendment to address this problem. After days of being ignored by his Democratic Party superiors and, finally, threatening to confront the media about his concerns, Bernstein’s request was met. Delegates at the 1965 Connecticut Constitutional Convention passed Bernstein’s amendment which guarantees free public education to every child. This set the stage for a series of prominent educational lawsuits, including Horton v. Meskill (1970), Sheff v. O’Neill (1989), and Connecticut Coalition for Justice in Education Funding (CCJEF) v. Rell (2005).

The Man Behind the Amendment

Bernstein was born on January 17, 1913, in Hartford, Connecticut. After graduating from Trinity College and Harvard Law School, he began his political career in Hartford as a lawyer and Democratic alderman. During his time in Hartford, Bernstein served on the city’s Finance Committee and also actively participated in the 1940’s Zionist movement, a political effort that sought to encourage local lawmakers to support Israel’s fight for its own state. In 1950, Bernstein moved to Bloomfield and was elected to the Bloomfield Board of Education.

In all of his political efforts, Bernstein proved he was not afraid to confront difficult issues that others were hesitant to address. For example, in 1947, Bernstein took on a legal case involving a racially restrictive covenant, a term used to describe real estate agreements that prohibit people of a specific race from occupying a property. This covenant, in particular, limited a property sale in the West Hartford area to “non-Semitic persons of the Caucasian race.” The Hartford Courant published an article about Bernstein on March 28, 1947, which wrote that Bernstein felt the covenant’s racially specific language was “against public policy.” Bernstein eventually managed to get this phrasing erased from the original property agreement, making him the first person in Connecticut to successfully address a legal case of this kind.

The Creation and Impact of the Education Amendment

One reason why Bernstein’s peers at the 1965 Connecticut Constitutional Convention attempted to stifle his enthusiasm for including an education amendment was that they were focused on only one task: revising the state’s system of political representation. Connecticut’s representation system needed to be fixed as a consequence of the 1964 United States Supreme Court ruling in Reynolds v. Sims. The Court found that the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause required state legislatures to apportion representatives based on each district’s population to ensure that all citizens are equally represented. This “one man, one vote” law thus made Connecticut’s system—two representatives for every district regardless of population—unconstitutional.

Because the sole purpose of the Convention was to align Connecticut’s representation system with Reynolds v. Sims, John Bailey, the influential Democratic chairman, had little interest in seeing any proposals regarding schools. However, this did not stop Bernstein from voicing his concerns about Connecticut’s lack of a constitutional guarantee to education: “I was enough of a history student of law, a lawyer, to know that once a convention is called for the state or national, nothing is irrelevant,” Bernstein stated in an interview. Rather than accept the legislature’s preplanned agenda, Bernstein chose to challenge his political superiors.

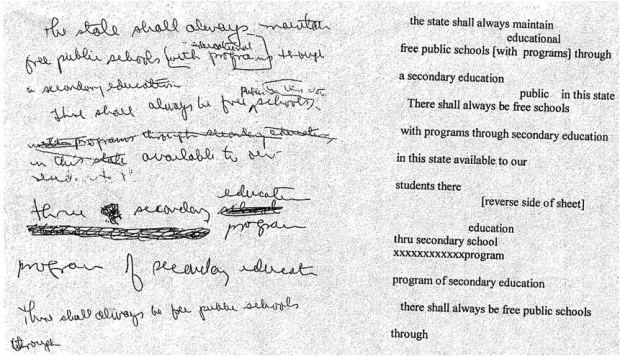

In order to gain the legislature’s attention, Bernstein repeatedly asked Bailey to consider his proposal and also threatened to discuss his frustration with the media. In the end, it was this threat that worked. Bailey granted Bernstein a meager 5 minutes to draft a proposal in an effort to quickly return to the discussion on political representation. Bernstein’s amendment, which he scribbled onto a scrap of paper in order to make his 5-minute deadline, is general because Bernstein believed the language of the Constitution should reflect overall principles and ideas. It states that, “There shall always be free public elementary and secondary schools in the state. The general assembly shall implement this principle by appropriate legislation.”

Bernstein was given only minutes to draft his proposal for what is known today as the 1965 Education Amendment. The above image is a facsimile of the document. The actual draft of the Article is held at the Connecticut State Library.

Although the world “equal” is not explicitly written in the amendment, its inference has been used as a foundation for nationally recognized educational inequality lawsuits such as Horton v. Meskill (1970), Sheff v. O’Neill (1989), and Connecticut Coalition for Justice in Education Funding (CCJEF) v. Rell (2005). At the time of Horton v. Meskill, Connecticut supplied school districts with $250 per child, forcing towns to rely heavily on local property taxes for additional funding. The Horton plaintiffs used Bernstein’s amendment to argue that this system was unconstitutional because it meant educational quality varied considerably from poorer to wealthier towns. Sheff v. O’Neill used Bernstein’s amendment to prove that the extreme racial, ethnic, and economic isolation of the Hartford school district left its schoolchildren, and suburban schoolchildren, with an insufficient education that the state was required to remedy. The CCJEF v. Rell lawsuit used the 1965 Educational Amendment to argue that Connecticut’s system for funding public schools was not only inadequate but also disproportionately harmed minority schoolchildren by diminishing their ability to participate in the democratic process, thrive in college, and reap the monetary rewards of intellectual success.

After his years as a lawyer, Bernstein served as a Connecticut Superior Court Judge for 27 years. He passed away on May 27, 2013, at his home in Sarasota, Florida, at the age of 100. His contribution to Connecticut lives on through the 1965 education amendment that continues to serve as a foundation for educational inequality lawsuits throughout the state.

Elaina Rollins, a sophomore at Trinity College in Hartford during the 2013-2014 academic year, is an Educational Studies major and a resident of Columbus, Ohio.

Simon Bernstein Interview, August 1, 2011 from Trinity College.