By Steve Thornton

Connecticut has no shortage of war memorials or statues featuring prominent business and political leaders. The celebration of the state’s ordinary working people, however, is almost nowhere to be found. One exception is Industry (sometimes referred to as The Craftsman) in Hartford. It is a striking example of a working man, created in 1931 by Evelyn Beatrice Longman and prominently displayed on the campus of the A. I. Prince Technical High School on Flatbush Avenue.

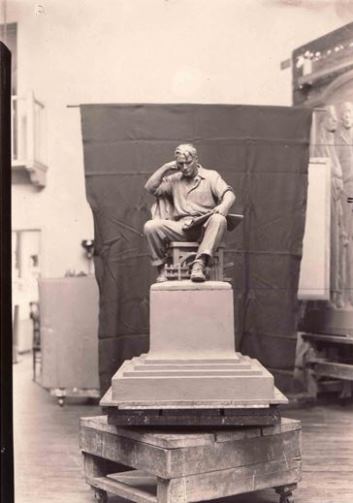

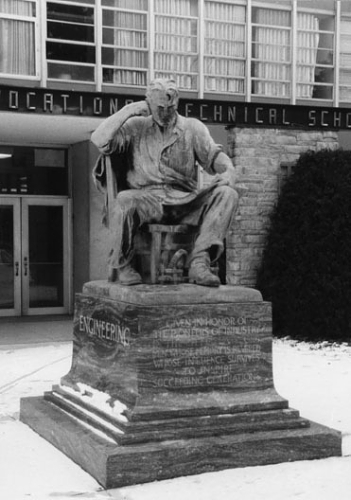

The bronze sculpture portrays a worker sitting and reading—his jacket thrown across a wooden chair. Dressed in rough clothes, worn work shoes, and rolled-up sleeves, his concentration is intense. In one hand is a tool of his trade; at his feet are machine parts. On his lap is a set of schematics. He is concentrating, and perhaps, puzzling out a repair.

Industry Finds a Home

Dedication of Industry took place on September 16, 1931, at the Hartford Trade School on Washington Street. The school and the statue moved to Hartford’s south end in 1960.

Evelyn Beatrice Longman, Industry, 1931, bronze sculpture, State of Connecticut A. I. Prince Regional Vocational-Technical School – Smithsonian American Art Museums, Art Inventories Catalog

The granite foundation on which the sculpture sits does not include the name of Longman’s work. Instead the words chiseled into the stone base read: “Given in honor of the pioneers of industry in the city of Hartford, men whose memory is revered, whose influence survives to inspire succeeding generations.”

The subject and the dedication seem like a mismatch. Industry clearly does not depict an “industrial pioneer”; the subject is a skilled worker, the kind employed by the pioneers. He is the nameless working man who made the pioneers successful. But the Connecticut Manufacturers Association commissioned and paid for the statue, so they had the last word.

In fact, around the time officials dedicated the statue, Connecticut was a hotbed of militant union organizing. Leading up to the unveiling of Industry, there were a dozen labor strikes throughout the state: textile workers in Putnam and New London, fur workers in Danbury, necktie and shirt makers in New Haven, and laborers in Newtown. Even unemployed workers struck—they were in a city-sponsored relief program at Hartford’s Brainard airfield and stopped work until they won transportation, food allowance, and a dollar-a-day raise.

Industry is not Longman’s only worker-themed sculpture, however. In 1911, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire took the lives of 146 New York immigrant garment workers, some as young as 14. The reckless tragedy spurred safety reforms and union organizing. A year after the fire, survivors dedicated the Triangle Fire Memorial to the Unknowns for the six victims who remained unidentified. The public never knew who created the monument, and it was only recently that Evelyn Longman received the credit for it.

Evelyn Beatrice Longman in Connecticut

Profile portrait of Evelyn Longman – Photograph from the collection of the Loomis Chaffee School Archives, Loomis Chaffee School, Windsor, CT

Evelyn Longman moved her New York studio in 1920 to the campus of Loomis School in Windsor, Connecticut, thanks to a commission she received to create a piece in honor of Nathaniel Batchelder’s late wife. Batchelder was the headmaster at Loomis; he and Longman eventually married. Batchelder proceeded to build her a studio with train tracks running through it—allowing clay and stone deliveries to arrive directly to her workshop.

By the time Longman completed Industry she was firmly established in her field. Besides a variety of local installations (many of which were full of military symbolism, including Spirit of Victory, a Spanish-American War memorial in Bushnell Park), Longman’s work appeared at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, she became the only artist for whom Thomas Edison agreed to sit, and around 1920, she began a commission to work on the Lincoln Memorial. There Longman created a number of decorative wreaths cut in stone and, it is said, she sculpted the humble rail-splitter’s hands from Georgia granite.

Steve Thornton is a retired union organizer who writes for the Shoeleather History Project