By Savahna Reuben

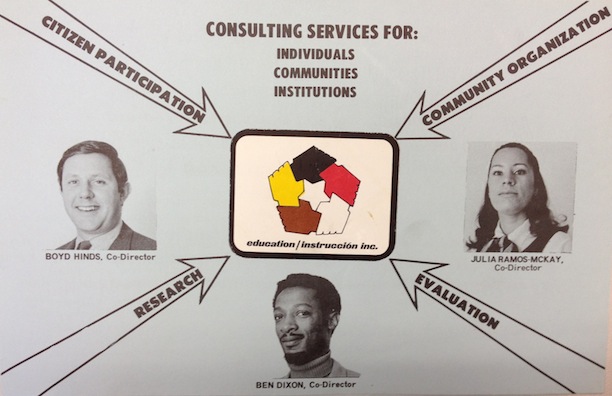

Glue, cut-up pieces of paper, and string—these were the tools used to initiate the fight against housing discrimination when Ben Dixon, Boyd Hinds, and Julia Ramos, individuals from very different backgrounds, came together to map out the power exerted by the largest, most influential real estate institutions in the Hartford community. It quickly became evident that those sitting on the boards and controlling the money, the housing laws, and the insurance rates were predominantly white and male—while the local populations affected by their decisions were far more diverse. Thus began the battle to uncover real estate discrimination in the area and put an end to this form of institutional racism.

Common Interests Form at Westledge School

Boyd Hines, a white male who grew up in a middle-class family in the suburbs of Hartford, introduced Ben Dixon to Julia Ramos when he offered them teaching jobs at Westledge School in West Simsbury, where he worked. This short-lived, private, and experimental institution attempted to provide a better education for Puerto Rican and African American boys. Julia Ramos, a Puerto Rican woman and University of Hartford graduate, served then as deputy director for the Poor People’s Federation. Ben Dixon, an African American man who grew up in Hartford, earned degrees from Howard University in Washington, DC, and Harvard Graduate School of Education, before returning to Hartford to teach music. Before long, the three decided that their work at Westledge seemed limited in its ability to combat racism as it existed within institutional structures.

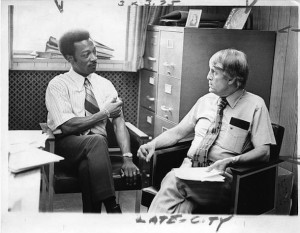

Title VII Director Dixon with Assistant School Superintendent O’Donnell, Hartford, 1968 – Hartford Times Collection, Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library and Connecticut History Illustrated

The three colleagues formed Education/Instrucción in 1970 to fight a legal battle against institutional racism. Equally important, they wanted to educate people about how these sometimes less visible forms of discrimination operated—often without the knowledge of the very people being denied equal rights and opportunities. Therefore, Education/Instrucción started out by offering consulting services and informative articles that coherently described the nature of housing biases and corrupt practices. The bilingual name of the group reflected its educational mission and also its vision of bridging gaps within the Hartford community to promote unified, multicultural cooperation for the common good.

Housing Market Testing Collects Evidence of Bias

To expose unfair housing practices in the Hartford area, Education/Instrucción launched Project Ya Basta. (The Spanish phrase “Ya Basta” is equivalent to “enough already” in English.) Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, better known as the Fair Housing Act, prohibited discrimination in the “sale, rental, and financing of dwellings, and in other housing-related transactions, based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, or familial status.” In practice, however, the act contained many loopholes and lacked strict enforcement.

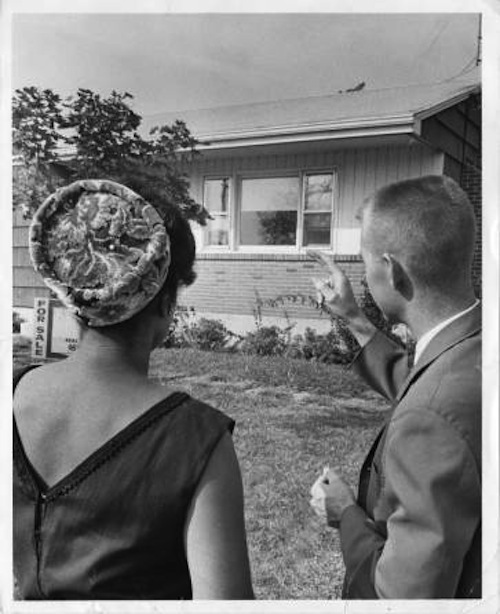

Education/Instrucción began its work by “testing” local market practices. Testing involved sending out individuals who acted as though they wished to buy a house. This method provided a way of measuring the accuracy of information and quality of customer service given to potential buyers of different backgrounds. For example, Mr. and Mrs. Hall, African American testers, collected data that formed the basis of their testimony in the court case US v. The Barrows & Wallace Co., et al. Without revealing any facts about their race, Mrs. Hall contacted the Mary Ellen Walsh and Dorothy Oasis real estate office. Over the phone, Mrs. Hall inquired about homes in the Greater Hartford area, west of the Connecticut River and within a price range of $25,000 to $30,000. After making an appointment to look at houses, per the testing plan, Mrs. Hall postponed the appointment over the phone, yet also inquired about the locations of the potential houses. The agent gave Mrs. Hall a variety of addresses located in the Hartford and West Hartford areas and insinuated that the Halls should move out of the Blue Hills area because of changes occurring in the neighborhood. When the same agent finally met Mrs. Hall in person, however, she only showed her houses in the Blue Hills area. Homes in other areas of Hartford, including West Hartford, suddenly became unavailable where, before the in-person meeting, a number of listings existed.

African American woman looking at home to purchase, Hartford, 1963 – Hartford Times Collection, Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library and Connecticut History Illustrated

US v. The Barrows & Wallace Co., et al

On April 19, 1974, six citizens, 15 community organizations, the Connecticut Coalition for Open Suburbs, and Education/Instrucción filed a suit against the Real Estate commission in New Haven Federal District Court. The complaint, entitled the “Title VIII Open Housing Complaint,” argued that real estate insiders in the state of Connecticut maintained biased real estate practices such as “racial steering” (encouraging buyers of certain races to move into particular areas), “blockbusting” (encouraging white homeowners to leave neighborhoods with growing minority populations and to sell their homes for a low price), and discriminatory hiring. With multiple sources of testing evidence demonstrating racist tendencies on the part of real estate companies and agents, many of the major corporations named in the suit decided to settle rather let the matter go to court. By winning this indirect admission of guilt from the industry, Education/Instrucción brought to light the unfair practices that suppressed equal access to housing and led to racially segregated neighborhoods in the Hartford region. The organization continued to hold meetings with clients up until Boyd Hines’s death in 1990.

Savahna Reuben, a senior and member of the squash team at Trinity College in Hartford during the 2014-15 academic year, is pursuing a double major in Educational Studies and Performance and Media. She contributed this essay during the 2013-14 academic year.