by Amy Gagnon

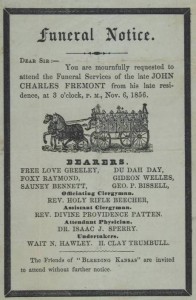

Funeral notice, ca. 1856 – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Online

Romance, sentiment, and strict moral conscience characterized much of expressive life in New England during the 19th century. Attitudes toward death and mourning practices were particularly important elements in this Victorian age. A central belief was the concept of a “good death,” that is, to die in the home, among family, and with a clear Christian conscience. For the dying, it was a time to give advice to family members, be absolved of sins, say goodbye, and peacefully transition to the hereafter. This time was equally important for the living; it allowed them to wake and mourn the deceased in the home with other family members.

The advent of the Civil War in the mid-1800s transformed the ways people in the North handled the death and mourning of loved ones. Because so many Union soldiers died during the war—and died far from home— the problems associated with properly laying the dead to rest and making sense of the unprecedented scale of human loss had a profound impact on Connecticut’s way of life.

Although Connecticut was one of the smallest states in the Union, its size did not stop large numbers of men from enlisting in the Union army. The state mobilized 30 infantries (including 2 African American regiments), 5 artilleries (both light and heavy), and 2 cavalries. In all, approximately 55,000 Connecticut men went off to war. Troops from the state fought in almost every major and minor battle of the Civil War, and casualties numbered in the thousands. Many more died in confederate prisons or were executed by the Confederacy.

Bringing the Fallen Home

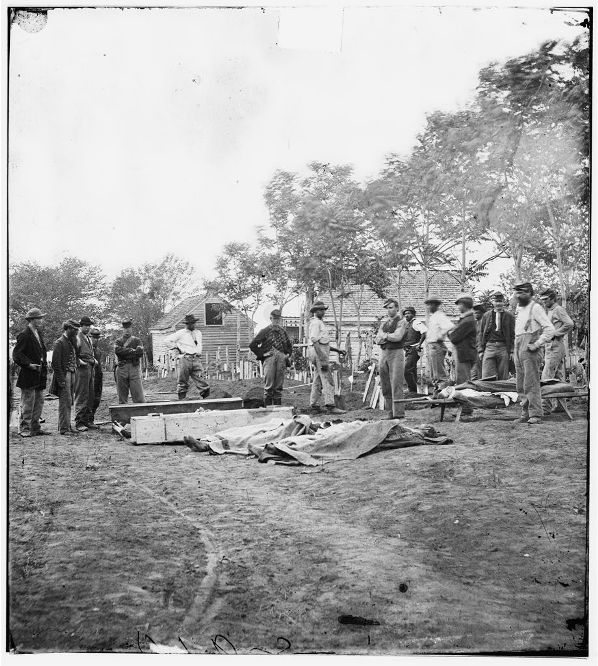

Burial of Union soldiers, Fredericksburg, VA, 1864

– Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

For those back in Connecticut, frequent funerals became a harsh reminder of the war’s toll. To add to the distress, death on the battlefield or far from home denied the deceased and their families the ideal of the good death. Oftentimes, families were not able to locate or identify the dead, and even when the deceased could be located, efforts to ship them home often failed. Still, many of the fallen were brought home. Trains transporting the dead were met at various stations throughout the state by crowds of hundreds, making once-private family grief a very public affair. For the Connecticut families that could afford to travel to recover their dead, the trip was often stressful. One Connecticut father remarked to a local newspaper that transporting his son’s remains from Washington, DC, to Winsted cost $125.00—almost $2,000 in today’s money—and the trip was not possible without “the personal attendance of some friend, and every step is attended by some incidental expense.”

Until 1864, General Ulysses Grant was lenient about permitting civilians to enter battlefields to retrieve their dead to bring them home for burial. As long as this practice did not hinder troop movement, families were allowed to search for their lost loved ones. Connecticut newspapers often reported—along with locations—“Rolls of Missing Men,” long lists of the dead for family members. After the Battle of Antietam family members and undertakers from all over Connecticut met on the battlefield, where they conducted over 200 funerals for the Connecticut troops killed there. Likewise, Connecticut families traveled to the battlefields of Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, and the Wilderness to retrieve their dead. It can be difficult for noncombatants today to grasp the impact such direct encounters with the war’s carnage had upon the citizenry.

Finding those who had been buried far from home, also proved difficult. Connecticut soldier Dorrance Atwater, taking his cue from then Civil War nurse Clara Barton, succeeded in obtaining copies of Union soldier interments while employed as a hospital worker. He was able to identify the graves of many Union soldiers who fell in the South so that their families could recover them. (He was later arrested and imprisoned for stealing the records). The rolls were not always accurate, however, and Connecticut newspapers sometimes had to print retractions. For example, in 1863 the Hartford Courant reported the death of Capt. Samuel Fiske of Madison only to retract the report after a witness saw him marching to Richmond as a prisoner.

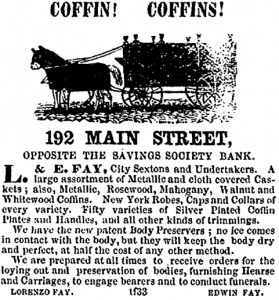

Advertisement for coffins, Hartford area, ca. 1963

The War Transforms Funeral Practices

The funeral in the Victorian age was a family event held in the home, with long periods of mourning, but the nature of war-related deaths disrupted such practices. It was at this time that various embalming methods emerged in hopes of returning the dead to their loved ones. But the new methods proved unreliable and rarely effective. When the dead did return to their families, they were often severely decomposed, or worse, not the family member at all. It was also during this time that casket companies began to construct various types of coffins to aid in transport and identification. For example, they made caskets with viewing windows so that the family could more easily identify their dead.

Honoring the Dead through Burial and Monuments

The Civil War era was also the time that local cemeteries began to transform. By the early 19th century, colonial burying grounds and churchyards located in towns and cities were overcrowded and largely ignored. To counter this, and in keeping with romantic sentiments of the Victorian age, the rural cemetery, set away from the town, emerged. Planners designed these cemeteries as park-like settings that encouraged visitors to wander paths, contemplate the solemnity of death, and feel God’s presence in nature. Hartford’s Cedar Hill Cemetery follows this thinking. Even though the first interment at Cedar Hill Cemetery occurred a few years after the Civil War ended, many who had died or served in the war were moved from other burial sites to this new resting place. Those whose remains were re-interred there include industrialist and Civil War arms manufacturer Samuel Colt, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, and General Griffin A. Stedman, Jr. of the 11th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry.

During and immediately following the war, Connecticut towns began to erect monuments to the soldiers who both fought in and were lost in the war. Berlin’s Soldiers’ Monument, erected in 1863, claims to be the first Civil War monument, not only in Connecticut, but in the nation. Today, there are well over 100 Civil War monuments in the state, with memorials still being erected. As recently as 1992, the town of Farmington dedicated a monument honoring the 362 townsmen who served in battle. Most monuments throughout Connecticut are located on town greens or in local cemeteries. They serve not only as a reminder of the Civil War but of the irrevocable changes that the conflict and its death toll left on Connecticut.

Amy Gagnon works as a content developer for ConnecticutHistory.org at Connecticut Humanities and received her MA in Public History at Central Connecticut State University.