Connecticut’s history is etched into its landscape: from millennia of presence and changing use/relationships by Indigenous peoples to the smokestacks of mill towns, and from filled tidal marshes to the revival of oyster beds. Over four centuries, patterns of resource use and abuse have repeated and most have prompted reforms by individuals, civic groups, regulatory innovation, and ecological restoration. Connecticut’s environmental story offers more than historical or scientific interest; it provides a roadmap for understanding how communities have responded to environmental challenges—and how those responses inform our approach to today’s climate crisis.

Indigenous Belonging and Colonial Transformation

Long before European settlers arrived, Native communities along Long Island Sound belonged to and relied on interdependent land and water systems. Their practices — controlled burns to maintain meadows, sustainable fishing techniques, and seasonal migrations — reflected a worldview of reciprocity in which humans were part of, and not superior, to the natural world. With an Indigenous population estimated at 10,000–15,000 by some sources on the Sound’s shores, stewardship was the rule rather than the exception.

Connecticut’s colonial era ended this natural balance. English colonists viewed forests, rivers, and soils as inexhaustible commodities to be exploited. They cleared forests for timber, crops, and pastures, and later dammed rivers for power mills. What began as small homesteads grew into an industrial landscape, setting a precedent for resource exploitation with little to no regard for long-term consequences.

Industrial Growth and Its Toll on the Water, Land, Air, and Public Health

From the 18th century onward, Connecticut’s rivers became industrial arteries. Mill towns sprang up along the Connecticut, Housatonic, and Naugatuck Rivers. Their dams provided hydro power for factories, resulting in wealth for their owners and products for a growing population. Unknowingly, the dams provided barriers to migrating Atlantic salmon and other anadromous/catadromous fish as noted in an 1870 Fish Commission report

“The salmon ascended the river as far as the dam and were taken in great numbers the first year. The following year they were still a plenty, and then they began rapidly to decrease in numbers, and at the end of four years they had nearly all disappeared”

Over time, these mill towns expanded their production of textiles and manufactured goods, with no regard for their impact on the land, water or air. New Haven’s health officer S. W. Williston reported to the General Assembly in 1886 that “nearly every stream adapted to manufacturing requirements in the state is contaminated” by acids, dyes, and other industrial waste. Some of these effluents flowed downstream to Long Island Sound and accumulated as “legacy contaminants” that persist today.

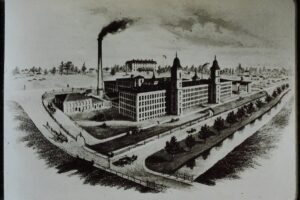

This textile mill, built in 1872, in the village of North Grosvenordale in the town

of Thompson, CT CC-BY-SA-4.0, Self-published work, B. Michael Zuckerman, BMZ: Connecticut Mills

In the early 1900’s, Connecticut businesses introduced plastics, explosives, and metal-finishing chemicals, adding to the environmental degradation and health problems. Meanwhile, municipalities discharged raw sewage unabated into urban streams and rivers. By the early 20th century, the Connecticut River, with discharges from New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, and Connecticut, was described as an “open sewer,” with dissolved oxygen so low in summer months that virtually no fish survived.

In mill towns such as Hartford, New Haven, Middletown and Naugatuck, air pollution from burning coal, kerosene, and wood, resulted in “pea-soup” coal-smoke fogs and widespread respiratory illness. A 1922 New Haven health report linked soot to bronchitis hospitalizations, prompting ordinances in New Haven and Hartford for minimum chimney height requirements and soot-trapping baffles. Yet air pollution remained an afterthought until the mid-20th century, when fouled rivers, decimated forests, and smoky cities collectively galvanized public advocates.

Between 1800 and 1940, Connecticut lost nearly one-third of its tidal wetlands when they were dredged, filled, or diked for expanding industry, agriculture, housing, and railroads. By 1930, East Haven, Groton Long Point, and Stratford lost over half their marsh acreage. The unintended damage included declining fish and shellfish populations, degraded water quality, and heightened flood risks.

Early Warnings and Environmental Action

In the late 1800’s farmers, like James Bradford Olcott and writers, including Mabel Osgood Wright, founder of the Connecticut Audubon Association, among other individuals raised concerns and warnings about the environmental harm. Another advocate at the turn of the century, T.S. Gold, a founder of the Connecticut Forestry Association, described its role in 1895 to “develop public appreciation of the value of forests and the need for preserving and using them rightly.”

One of the more successful actions was a lawsuit by an alliance of farmers and mill owners downstream from Danbury who were harmed by discharges from its sewers. In a landmark decision, Judge George Wakeman Wheeler ruled in Morgan v. Danbury, that Danbury had created a public nuisance to the detriment of the riparian rights of downstream users and ordered the city to build a proper treatment plant within 2 years. The city built an efficient treatment system, as ordered, showing the power of using the judicial system to protect individuals and property from environmental harm.

Continuing Environmental Threats and Responses

World War II and the post-war boom intensified pollution: increasing factories and populations overwhelmed the environment. Seventy-five percent of shoreline towns had inadequate sewage infrastructure, with untreated waste flowing into Long Island Sound. In 1969, EPA surveys declared parts of western Long Island Sound “severely eutrophic,” with high levels of nitrogen and algae bloom and widespread fish kills, as oxygen levels plummet. Meanwhile, harbor sediments off Bridgeport, New Haven, and Stamford contained high levels of copper, lead, and PCB’s that rendered local shellfish unsafe to eat.

These crises in Connecticut and other states spurred action in the 1970’s and beyond. In 1971, Connecticut created the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), combining the State Park and Forest Commission with the Department of Agriculture and Natural Resources and under one agency to better meet the State’s needs and advance environmental quality legislation. In 1972, The Federal Clean Water Act established national water-quality standards and required discharge permits. Connecticut adopted secondary-treatment mandates by 1978, while DEP consolidated oversight of monitoring, permitting, and enforcement.

Regulation alone was not enough. Nonprofits and citizen groups filled critical gaps. In 1978, Connecticut Fund for the Environment (n/k/a Save the Sound) challenged polluters in court. In the mid 1980’s, the Long Island Soundkeeper Program empowered volunteers to monitor waterways and litigate under the Clean Water Act. Upgrades to major sewage-treatment plants, eelgrass plantings, oyster-reef restorations, and targeted sediment cleanups transformed degraded sites into thriving habitats. Local land trusts complemented these efforts: the Guilford Land Trust’s Audubon Loop preserved marshland in 2005, and the Westport Land Trust secured critical wetlands in 2014, ensuring green corridors for wildlife and people.

Over the years the DEP’s role also grew, as new environmental issues emerged and as it took on responsibilities delegated to the states under various federal programs. New legislation in 2011 gave the DEP responsibility for developing and implementing state energy policy and change its name to the Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP).

Confronting Climate Change: Challenges and Responses

Rising seas and extreme storms fueled by climate change now compound centuries-old environmental issues. Since 1950, Connecticut’s coast has seen roughly 0.12 inches of sea-level rise per year—nearly eight inches total by 2020. Warming ocean waters have created more life-threatening extreme weather events. Two “100-year storms”, Hurricane Irene and Superstorm Sandy, devastated Connecticut coastlines in consecutive years, 2011 and 2012 respectively. The state responded by funding and directing state agencies and local municipalities to take appropriate action. DEEP’s Coastal Management Act funds shoreline mapping and updated evacuation routes; the Connecticut Institute for Resilience & Climate Adaptation (CIRCA) provides grants for stormwater and community resilience projects. Connecticut municipalities have also adapted to climate change and extreme weather by upgrading infrastructure, adopting climate-informed land use policies, and utilizing state resources and financing programs.

New Haven, Coast Guard Flyover of Long Island post Hurricane Sandy, October 30, 2012, U.S Coast Guard photo by Petty Officer Rob Simpson

Connecticut’s responses blend mitigation and adaptation. In recent years, the state has taken pro-active steps to expand energy efficiency programs, deploy clean energy resources, and reduce carbon emissions into our atmosphere. In 2011, Connecticut was the first state in the nation to create a “green bank”, a quasi-public entity that leverages public funds to attract private investment for clean energy and environmental infrastructure in Connecticut, becoming a model for other states and the world. In 2022, the Connecticut General Assembly passed the Global Warming Solutions Act, which codified greenhouse-gas targets—45 percent below 2001 levels by 2030, 80 percent by 2050. The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (since 2008) caps carbon dioxide released from power plants.

Connecticut became a leader in environmental and climate education after years of local lobbying efforts by adult and youth advocates. In July 2023, it became the second state in the nation (after New Jersey) to require K-12 public schools to teach climate change in science classes. And in October 2023, the Connecticut State Board of Education unanimously adopted new social studies content standards that include climate change, sustainability, conservation and other aspects of environmental literacy for K-12 public schools.

Lessons for Today

Connecticut’s environmental history shows a familiar cycle: resource development and degradation lead to public outcry, investigations, legislation, policy innovations and often restoration or remediation. Each era’s solutions have built on previous efforts, demonstrating the value of persistence and collaboration by individuals, community groups, and state leaders. From 19th-century fish commissions to 21st-century activism and volunteer cleanups, grassroots action has been a constant driver of change. While the scientific specifics (e.g., dissolved-oxygen thresholds) may seem technical, the broader narrative reveals how accurate data informs sound policies.

One new development is that Connecticut has taken a leadership role nationally in response to human induced climate change. In addition to its proactive efforts to mitigate rising temperatures and adapt to climate change perils, Connecticut has inspired other states, through its novel s Green Bank, to leverage public funds to attract private investment in clean energy and infrastructure. Similarly, Connecticut leads the nation in educating students in their science and social studies classes to be environmentally literate and prepared for a future altered by climate change.

Jim Clifford, a former lawyer and social studies teacher, is the director of Exploring Climate, and the state lead for the Connecticut Climate Education Hub.