By Rena Tobey

Aaron Draper Shattuck (1832 ̶ 1928) reinvented himself in response to his Connecticut world. Once a prolific landscape artist, Shattuck moved his family to Granby, Connecticut, in 1870, fostering his transformation from “stuck up” sophisticate with “citified ways” to a gentleman farmer driven by invention and fascinated with animal husbandry.

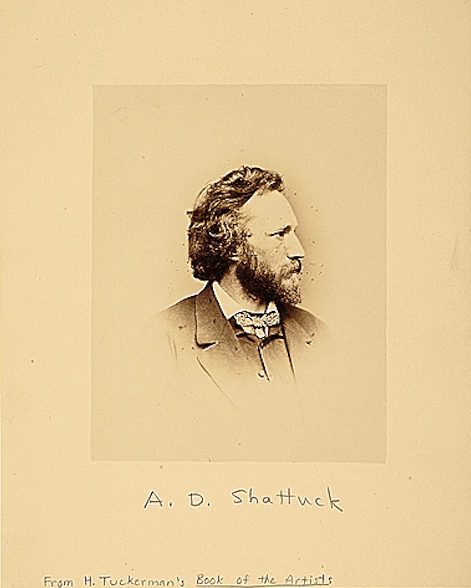

Portrait of landscape painter, Aaron Draper Shattuck by George Gardner Rockwood, ca. 1865-1867 – Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

Aaron Shattuck the Painter

Shattuck originally took up painting with Alexander Ransom in Boston. Following his mentor to New York City in 1852, he continued his art education at the National Academy of Design. Initially, he painted portraits, a secure way for an artist to make a living. But like many American artists in the mid-19th century, Shattuck was drawn to landscape painting (made popular by the Hudson River School).

One of the leaders of this artist community, Asher B. Durand, took an interest in Shattuck. Durand, building on the landscape philosophy of John Ruskin, urged his followers to paint directly from nature, capturing the details and feelings of the land. Shattuck originally painted in the style of more established artists, with dramatic scenes of the White Mountains.

Joining other artists who traveled around New York state and New England for inspiration during the summer, Shattuck met Marian Colman (through her artist brother Samuel). Aaron and Marian married in 1860 and continued to summer around the region, before having six children.

Enamored with Farmington River Life

When Shattuck fell in love with the Farmington River Valley, he bought a 28-acre farm in Granby—then known as a cattle town. Marian, the daughter of New York publisher Samuel Colman, was accustomed to the sophisticated, intellectual life of the city, however. Even though the family moved to the farm, they continued to winter in New York.

Unlike his colleagues who traveled to Europe for art training, Shattuck never wandered again from the Granby area. Profoundly inspired by the meadows, streams, fields, and rolling hills outside his farmhouse door, his painting style settled into the pastoral. Rather than awe-inspiring, Shattuck’s landscapes conveyed a harmonic relationship between humans and the land, a peaceful meditation on the timelessness of land, sky, water, rocks, trees, and plants.

Aaron Draper Shattuck, Cattle with Elms, ca. 1852-1928, oil on canvas – New Britain Museum of American Art, Bequest of Rita Heimann

Alongside his painting, Shattuck developed interest in scientific farming. He invested particular energy in breeding cattle and sheep, and his interest became evident in the increasing importance the animals took in his paintings. One critic even commented that his works were more like “animalscapes” than landscapes, emphasizing the farm animals in lieu of a celebration of land.

By the late 19th century, the calm coexistence of Shattuck’s two worlds began crumbling. He nearly died from a simultaneous bout of measles and pneumonia. His friend Jervis McEntee wrote in his 1879 diary that Shattuck was already disenchanted with his artist life, that he was “not advancing in his art.” Landscape-style preferences were shifting away from the pastoral to more Impressionistic, and with his unchanged vision, Shattuck’s sales dropped. His illness served as a convenient excuse to leave his 37-year painting career behind.

The Granby Inventor

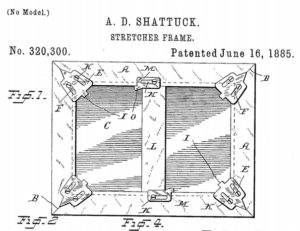

By the time he had largely given up on painting, Shattuck had already begun turning his creative energies to invention. In 1883, he patented a stretcher key that was manufactured in New Britain out of cast iron. The Shattuck Stretcher fit into a painting frame to hold corners in place, and soon became an industry standard. Popularized by his famous artist colleagues, over 3 million keys (in five sizes) sold from 1884 to 1917.

He followed the stretcher key with a cross-bar for stabilizing canvases, patented in 1885. For a man who at 22 noted in his diary that he had “$167.14 in hand,” these inventions made Shattuck wealthy.

An inveterate inventor and experimenter, Shattuck spent similar energies ensuring the success of his farm as well. He took great pride in his flower gardens, the strawberries that grew “as large as tomatoes,” and apple trees he grafted himself. Through selective breeding, he populated his yard with chickens that laid triple-yolked eggs. He also invented a horizontal-louvered ventilation system for tobacco barns and hand-carved at least four violins. One of these instruments featured mother-of-pearl designs considered “beautiful in tone” and exquisitely crafted.

When he died at 97, he left an estate worth over $500,000. His Granby neighbors “remembered him as a well-dressed gentleman who would stand, waiting for the stagecoach, with his black cape thrown back, a black, silk top hat on his head, and a gold-topped cane in his hand.” But Shattuck was a farmer, too, bringing the two Connecticut worlds of art and the land together in sun-drenched harmony.

Rena Tobey is an American art historian, providing talks and tours around the state. She has also created Artventures! Game—a party game on the adventures of art and art history.