By Edward T. Howe

Commercially successful production of common pins – traceable to the early 19th century – started in Connecticut. For the latter half of the 19th century and for much of the 20th, Connecticut led the nation in pin production (i.e., common, hairpin, and safety pins). Located primarily in the western Naugatuck Valley, the industry had advantages of easy access to the brass industry, marketing distribution channels, competent management, a readily employable labor supply, and sustained demand from buyers. It was not until after competitive pressures gained momentum in the latter half of the 20th century that the industry fell into serious decline.

Early Pin Making

Archeological evidence of handmade pins – formed either from thorn, fish bone, wood, ivory, iron, or bronze – can be traced to ancient civilizations in East Asia, North Africa, the Middle East, and Europe. In the 17th century, handmade pin manufacturing advanced in England using a wire-drawn process and a multi-step division of labor. After settlement expanded in the American colonies in the 17th and early 18th centuries, crudely crafted handmade pins appeared through the efforts of individual craftsmen. American endeavors to create a pin “industry” during the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, when British supplies disappeared, proved largely unsuccessful, however.

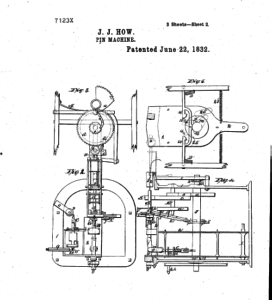

Connecticut doctor John Ireland Howe patented his first pin machine to mass produce spun-headed common pins in 1832. Following limited commercial success in New York, he moved his business to the Birmingham section of Derby under the urging of Anson Phelps (who opened a mill to make copper sheets and brass wire in Derby in 1836). Phelps assured him of plentiful supplies of brass wire, skilled and unskilled labor (men and women), and waterpower.

Pins made by Howe Manufacturing Co., Birmingham – Connecticut Historical Society

By 1841 Howe had patented a more efficient solid-head pin machine that used less metal than its predecessor. Basically, its complex operation involved inserting brass wire into one end of the machine, cutting it into its required length, sharpening and polishing one end of the pin, and forming the other end into a head. His contribution was using rotary tables (to hold the pins being processed and move them from place to place), rotary files (to grind the pin points), and cams (to control various operations). This machine proved initially capable of producing more than 24,000 pins a day.

Howe had competition, however. Samuel Slocum introduced his own solid-headed pin machine in 1838 in Poughkeepsie, New York, but produced his pins in secret since he did not file for a patent. Around the same time, the firm of Maltby Fowler and Sons began producing patented pins in Northford (North Branford).

Connecticut Leads America’s Pin Industry

In 1845 the State of Connecticut issued a report that covered business activity within its various cities and towns. It showed that the Howe Manufacturing Company employed 70 workers who made 150,000 pounds of pins in that year (valued at $60,000), while the Brown and Elton firm employed 50 workers who made 200,000 packs valued at $100,000. A year later Brown and Elton and the Benedict and Burnham Manufacturing Company (1834) established the American Pin Company as an outlet for their brass wire businesses.

The arrival of the Naugatuck Railroad in 1849 commenced a broad geographic effort to reach a wider array of industrial, commercial, and household pin users in distant markets. Prior to that, slow-moving, horse-drawn wagons transported pins and other goods to rural areas to be sold by Yankee peddlers, mostly to housewives.

The second half of the 19th century witnessed continuing growth and national ascendancy for the Connecticut pin makers. More firms entered the market, output focused on the production of safety pins and hairpins, and technological improvements in production continued unabated. During the 1860s three more Connecticut firms joined the industry. In 1860 the United States Pin Company began making iron pins in Seymour under Thaddeus Fowler, a son of Maltby; the Star Pin Company began making common and safety pins in Shelton in 1867; and Blake and Johnson, a joint stock company (1852), started making hairpins sometime during that decade. Other firms included the Pyramid Pin Company of New Haven, H. Twitchell and Son of Union City/Naugatuck, the Wyoming Pin Company of Winsted, the Jewell Pin Company (which opened in Hartford in 1881), and the Sterling Pin Company of Derby.

20th-Century Dominance and Decline

Although independent data for the pin industry was not available after 1860, the US Census Bureau did provide some special statistics for 1914 and 1919 that showed how Connecticut firms dominated the industry. In 1919 the Connecticut pin makers produced 81.0 percent of all common pins in the United States, with a value of $2,260,239; 32.9 percent of all metal hairpins, with a value of $486,849; and was the leading state in the production of safety pins. Hairpins, particularly bobby pins – an invention of Luis Marcus in Paris in 1899 – had been gaining in popularity since their introduction in the United States at the turn of the 20th century.

Detail from patent for John Howe’s pin machine. Filed June 22, 1832.

Given the prosperity of the pin industry in the early years of the 20th century, it was surprising when the venerable Howe Manufacturing Company filed for bankruptcy in 1906. Two years later its assets were acquired by the Plume and Atwood Company of Waterbury, a large brass products firm. Shortly thereafter two smaller firms closed – H. Twitchell and Son in 1909 and the Jewell Pin Company in 1911. The continued profitability of the American Pin and Oakville companies led the Scovill Manufacturing Company (already producing some pins) to acquire both of them in 1923 to further diversify its products and help stabilize its finances. The Star Pin Company then acquired the New England Pin Company and the National Pin Company of Detroit in 1926 in an effort to remain competitive with Scovill, now the largest pin producer.

By 1962 another look at the condition of the pin industry became available when the US Tariff Commission undertook a required escape-clause investigation of common and safety pins. At this time the production of brass or steel common pins was dominated by the Oakville division of Scovill; the Star Pin Company; the Union Pin Company; and the Dorset-Rex Company of Thomaston (bought by Risdon in 1965). Imports in the period for both types of pins were on the rise and came mainly from England, West Germany, and Czechoslovakia. A further investigation in 1982 simply stated that shipments by producers of common and safety pins had fallen from $21 million to $13.5 million between 1977-1981 as imports rose sharply, particularly from Asian nations.

A rising level of imports after 1950 was not the only problem for the pin makers. Common pin production was affected by declining domestic output of shirts and other apparel due to cheaper imports, growing usage of plastic tags for clothing, and increased usage of paper clips and staples for fastening paper. Safety pin production was hampered by the use of fasteners on diapers, offset somewhat by demand for home sewing needs. All of this provided less incentive to invest in aging plants that proved expensive to operate. The result was that the remaining firms either closed or moved away.

Edward T. Howe, Ph.D., is a Professor of Economics, Emeritus, at Siena College near Albany, New York.