By Nancy Finlay

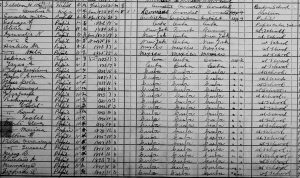

The 1900 Federal Census lists 29 children, between the ages of 7 and 24, living with Henry M. and Caroline Selden in Old Saybrook. Twenty-four of the children were born in Cuba or have a Cuban parent—the rest were from Puerto Rico, Mexico, New York, and an unidentified Central American country. In addition, the census also includes four young adult teachers—mostly Cuban—and an older “Principal”—most likely Susan Strong, Caroline’s sister. Although the census identifies Mr. Selden as the “Head” of this “Cuban School,” all other contemporary references indicate that Mrs. Selden was the school’s founder and director.

Teaching and Missionary Work

Former Seabury Institute in Old Saybrook where Caroline Selden took her Cuban students during summers – University of Connecticut Libraries Archives and Special Collections

Caroline Mehitable Strong was born in Middle Haddam on June 9, 1832. Little is known of her early life, but in January 1874, she joined the Protestant mission in Monterey, Mexico run by the American Board of Foreign Missions. Caroline was in charge of the school for girls and while the boys’ school had trouble attracting and retaining pupils, Caroline had about 30 girls in her classes. Contemporary sources noted that the students showed “progress in [their] study” which offered “good promise for the future.” In 1886, Caroline founded the Evangelical Aid Society for the Spanish Work of New York and Brooklyn, which offered a day school for the children of Spanish-speaking parents, Sunday schools, and an industrial school where young women learned sewing.

Cuban School

In 1895, Caroline married Henry M. Selden of Haddam Neck, Connecticut, and the couple established a home in Brooklyn, New York, where Caroline continued to carry out her missionary work. At the time, Brooklyn had a substantial community of Cuban exiles—many took part in a recent rebellion against Spanish rule and continued to work for Cuban independence.

Another rebellion, the War of Independence, broke out in Cuba in February 1895. Attempting to quash widespread popular support, the Spanish army rounded up hundreds of thousands of civilians and confined them to designated areas to prevent them from helping the rebels. Estimates vary, but this policy—known as “reconcentration”—killed perhaps as much as a tenth of the island’s population. Sympathy for the Cuban people—especially Cuban children—ran high in the United States.

Caroline Selden responded by opening a school for the daughters of Cuban refugees in Brooklyn. While newspaper accounts stress that the girls were the children of Cuban patriots and freedom fighters, most, if not all, of them appear to have been both white and well-to-do. The school was in operation as early as 1897 and in 1898, when the United States declared war on Spain and American troops joined the fighting in Cuba, Caroline announced an ambitious plan to accommodate one thousand or more Cuban pupils. Although such an expansion of her program never took place, in 1900, she filed articles at the state capitol in Albany incorporating the Cuban Home Training School of New York—naming herself and her husband among the directors.

Between 1900 and 1902, Caroline and her pupils spent a substantial portion of the year in Old Saybrook—from about June to October or November. They occupied the former Seabury Institute—a military boarding school operated by the Reverend Peter Lake Shepard from 1865 to 1886. By this time, in addition to girls, the school included male students and teachers. Some of the students accompanied Caroline on her travels about Connecticut, singing and giving recitations, while she lectured about the situation in Cuba and attempted to raise money to support the school.

Americanizing Cubans

The defeat of Spain did not lead to the immediate establishment of an independent Cuba. Instead, the US army occupied Cuba until 1902. One goal of the occupation was to “Americanize” the Cubans through a program of compulsory education, in the hopes that it would lead them to accept American influence. Thousands of Cuban teachers and students came to the United States during this period to be educated—Caroline Selden’s school was a small part of that larger effort. Mrs. Selden hoped that her pupils would return to Cuba as teachers and missionaries imbued with American ideals.

There are no references to the school after 1902—perhaps because of the end of the military occupation of Cuba or because Henry Selden died that year. Lola Zayas, one of the Cuban girls who was living in Old Saybrook with the Seldens in 1900, was still living with Mrs. Selden in Brooklyn in 1905. Caroline Selden lived in Brooklyn until her death in 1917, but she is buried in Haddam Neck with her husband. Her obituary noted that she “was somewhat known in Connecticut as a missionary, being engaged in that work for forty-five years” and that “she conducted the Cuban Mission in New York for several years.”

Nancy Finlay grew up in Manchester, Connecticut. She has a BA from Smith College and an MFA and PhD from Princeton University. From 1998 to 2015, she was Curator of Graphics at the Connecticut Historical Society.