By Patrick J. Mahoney

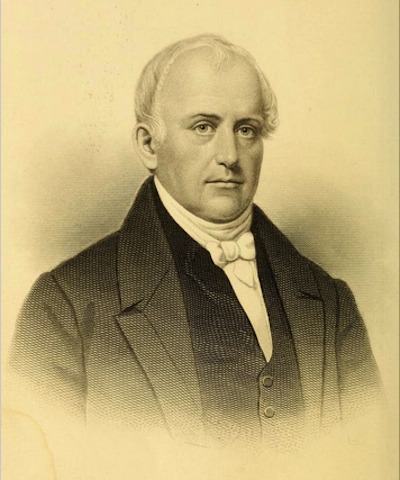

In 1793, Samuel Slater, a native of Derbyshire, England, ushered in the American Industrial Revolution when he constructed America’s first textile mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. As a young boy, Slater learned the intricacies of industrialization while working in a cotton mill in his hometown. Within three years of establishing his first mill in Pawtucket, the operation had 30 workers, the majority of whom were children aged seven to twelve. Despite the many dangers and health risks associated with this work, mills sprang up throughout the New England colonies, bringing about an unprecedented boom in profits, and the need for a cheap, sustainable labor force.

Portrait of Samuel Slater from the book Samuel Slater and the Early Development of the Cotton Manufacture in the United States by William Bagnall, 1890.

Connecticut Child Labor Reforms

In accordance with the precedent set by Slater, factory owners typically favored children as a staple of their workforces—they believed them to be more manageable and cheaper than adult laborers. While the employment of young workers was economically advantageous to factory owners, reformers viewed the system as a form of exploitation.

In May 1813, Connecticut became the first state to enact a child labor law requiring employers to provide some schooling in the areas of reading, writing, and mathematics. Additionally, owners became accountable for the moral instruction of their young employees, with the requirement that all working children engaged in religious worship. The law did not address the minimum age of the workers, however.

In 1824, state civil authorities in areas where factories and other manufacturing firms operated began to establish groups known as “boards of visitors.” The state required members of these boards to visit workplaces and ensure that employers complied with the provisions of the act of 1813. If found in violation, factory owners faced fines of up to $100.00.

The push for child labor law reforms continued to progress throughout the 19th century, on both the national and state levels. In 1848, Pennsylvania set the minimum age for factory workers at 12, becoming the first state to implement legislation pertaining to the minimum age of child laborers. By 1900, 24 states, including Connecticut, followed suit and set the minimum age for non-agricultural jobs at 14 and strictly limited the working hours of those between 14 and 16 years of age. Despite such legislative action, the issue of child labor was far from resolved.

In the summer of 1902, a large corporation that managed a profitable cotton duck operation in New Hartford announced they were closing their Connecticut locations and moving all of their operations to the South where there were no regulatory laws regarding the age of child laborers like the ones found in Connecticut. This episode proved indicative of a much larger migratory trend that undermined reforms in Connecticut and other progressive-minded states. In a piece condemning corporate greed and calling for further reform, the Hartford Courant reflected, “So long as Georgia, for instance, allowed child labor, it would not do for Alabama to pass restrictive laws which would drive the workers across the border, for the mill population was migratory, and the demand for workers so great that mills habitually paid the moving expenses of employees hired from a distance.”

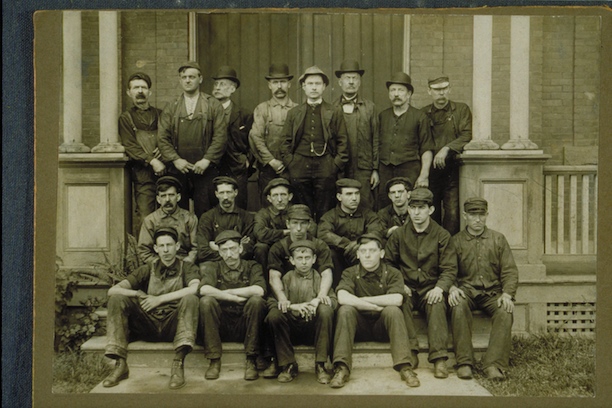

Wethersfield Avenue day crew, Hartford Street Railway Co., 1907 – Connecticut Historical Society

In 1916, the US Congress passed the short-lived Keating-Owen Act, which President Woodrow Wilson signed into law. The act prohibited the interstate sale of any goods produced by companies that employed children under 14, or mines that employed children younger than 16.

Presenting the Horrors of Child Labor to Hartford

A year after their lobbying success in Washington, the Connecticut chapters of the National Consumers League presented a child labor show in Hartford’s Old City Hall, at which various posters and cartoons adorned the walls, and information regarding the history and current status of child labor in Connecticut were presented to attendees. Many displays noted that while Connecticut had traditionally been a leader in pushing for labor rights, there was still significant room for improvement to its policies. One poster challenged attendees as follows: “Twenty-eight states do not permit children under 16 years to work in stores at night. Does Connecticut care less for its children than these states?”

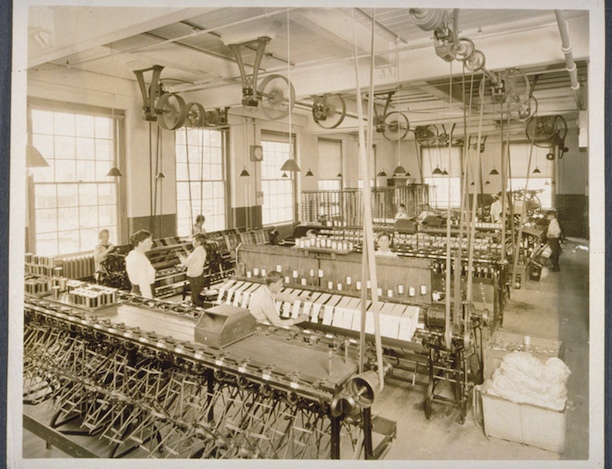

Mill interior, Cheney Brothers Silk Manufacturing Company, 1918. Woman supervising boys at work, apparently winding silk thread – Connecticut Historical Society

In 1937, as the country slowly emerged from the depths of the Great Depression, labor issues were again at the forefront of senatorial reform. Amid the desperate economic climate of the 1930s, with unemployment numbers soaring, adult laborers became willing to work for the same low wages as their adolescent counterparts. An increase in the number of adults willing to work for low wages allowed for reform to push forward, without the pressure from companies who feared for their profitability.

In 1937 President Franklin D. Roosevelt appealed to 19 states to ratify a child labor amendment to the Constitution that provided Congress with the power to regulate and prohibit the labor of persons under the age of 18. While a similar amendment in 1935 proved unsuccessful, and met with stiff resistance in the Connecticut House of Representatives, Roosevelt’s later appeal passed and eventually formed a part of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. In addition to the introduction of the 40-hour work week, minimum wage, and overtime pay, the statute prohibited the employment of minors in “oppressive child labor.”

Patrick J. Mahoney is a Research Fellow in History & Culture at Drew University and former Fulbright scholar at the National University of Ireland Galway