By Amy Gagnon

Charlotte Perkins Gilman was a noted writer, lecturer, economist, and theorist who fought for women’s domestic rights and women’s suffrage in the early 1900s. Born in Hartford to Frederick Beecher Perkins and Mary Fitch Westcott Perkins, Charlotte Anna Perkins had one brother, Thomas Adie, 14 months her senior. Her great-grandfather on her father’s side was Dr. Lyman Beecher, the renowned Calvinist preacher. Especially proud of her family lineage, Gilman revered her great-aunts Harriet Beecher Stowe, the noted novelist; Catherine Beecher, an advocate of higher education for women; and Isabella Beecher Hooker, a leader in the demand for equal suffrage.

Her father abandoned the family when Charlotte was very young, and her mother moved often with her children from relative to relative, and they lived mostly in poverty. Gilman spent much of her youth in Providence, Rhode Island, and while she had very little formal education, she attended the Rhode Island School of Design for two years (1878-80) and supported herself there as an artist designing greeting cards.

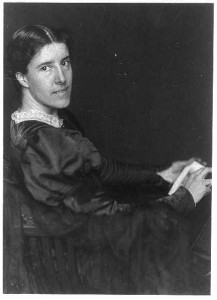

Charlotte Perkins Gilman – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Medical Crisis Inspires Social Activism

In 1884, at the age of 24, Gilman married aspiring artist Charles Walter Stetson and the following year bore their only child, Katharine Beecher Stetson. Soon after the birth, Gilman suffered from a serious bout of what today would be diagnosed as post-partum depression. While she had often been melancholy growing up, motherhood and married life pushed Gilman to the edge. She sought treatment for her “nervous prostration” with Dr. Silas Weir Mitchell of Philadelphia and in 1887 took the controversial “Rest Cure,” a treatment that included extensive bed rest, that he had pioneered. Gilman was fed, bathed, and massaged; she responded well to treatment and after a month was sent home with the prescription to live as domestically as possible, keep her child with her at all times, lie down for one hour after each meal, and to never touch a pen, brush, or pencil for the rest of her life. Her depression returned, however, and soon after coming home Gilman separated from her husband of four years—such separation being a rare event in the 19th century. She later lamented, “It was not a choice between going and staying, but between going, sane, and staying, insane.”

After the separation in 1888 (they divorced in 1894), Gilman moved with her daughter to Pasadena, California, where she began her professional life writing plays and poetry as well as fiction and non-fiction works, some of which were published in progressive magazines. At the same time, Gilman became active in social reform movements and was an advocate of the Nationalist movement, which began with the publication of Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward (1888), a novel depicting a Socialist, Utopian future. She lectured and dedicated herself to feminism and social reform, believing that a purely domestic environment oppressed women, that men dominated women, and that motherhood should not prohibit a woman from working outside the home.

A Prolific Writer on Women’s Issues

In her famous treatise, Women and Economics (1898), Gilman theorized that women could never be truly independent until they first had economic freedom. While many of these themes were explored through her lectures and papers (Gilman produced more than a thousand works of non-fiction), they also permeated her fiction. In 1892, she published her now-famous semi-autobiographical story “The Yellow Wallpaper.” Loosely based on the rest cure she received under Dr. Mitchell’s medical supervision, the story depicts a woman sent to “rest” in the bedroom of a rented summer home. The narrator’s husband, a physician, does not believe she is really ill and describes her malady as hysterical tendencies. The woman, however, descends into madness. While the story received mixed reviews, Gilman contended that her purpose in writing it was to reach Dr. Mitchell and show him the failure of his treatments. (She sent him a copy but never received a response.)

In 1894, Gilman sent her daughter to live with her ex-husband and his second wife, Grace Ellery Channing, a close friend of Gilman’s. This, like the separation and divorce beforehand, was not a common occurrence in the late-19th century, but Gilman held progressive views regarding paternal rights and believed that both Stetson and Katharine had the right to know one another. In 1900, Gilman married her first cousin, George Houghton Gilman. Over the next 25 years, Gilman wrote and published more than a dozen books and ran her own magazine, The Forerunner, in which many of her stories appeared. When George died suddenly in 1934, Gilman returned to California to be near her daughter.

Just two years earlier, in 1932, Gilman had discovered that she had inoperable breast cancer. An advocate of euthanasia, Gilman ended her life at the age of 75 with an overdose of chloroform, writing in her last letter that she “preferred chloroform to cancer.”

Gilman’s literary reputation declined in the years before her death, and her ideas regarding women’s roles seemed outmoded in the early 20th century. The advent of the women’s movement in the 1960s, however, brought about a revival of attention to her work. In 1993, a poll named Gilman the sixth most influential woman of the 20th century, and in 1994 she was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, New York.

Amy Gagnon worked as a content developer for ConnecticutHistory.org at Connecticut Humanities and received her MA in Public History at Central Connecticut State University.