In 1941, with war raging on the European continent, the United States government anxiously pursued opportunities to establish an air base in Connecticut to bolster defenses along the East Coast. In response, the state of Connecticut purchased 1,700 acres of tobacco farmland in Windsor Locks and leased it to the federal government. This new base became Bradley Field and served as a training post for air combat units, a staging area for overseas military deployments, and a camp for housing German prisoners throughout the remainder of the war.

The Connecticut General Assembly agreed to purchase the land for Bradley Field at the urging of Governor Robert A. Hurley. Once the state completed the purchase, it leased the land to the federal government for a period of 25 years. Originally named the Windsor Locks Army Air Base, the military installation was up and running by the summer of 1941.

Base in Windsor Locks Gets a New Name

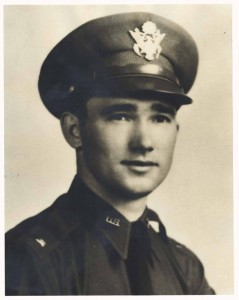

Late that summer, a 24-year-old, newly-wed pilot named Eugene M. Bradley lost control of his P-40 fighter plane during a training exercise and died. Bradley was the first of many pilots to die in training accidents at the field over the course of the war. In his honor, the Army officially renamed the base, “Army Air Base, Bradley Field, Connecticut.” Since that rededication in January of 1942, the base has been informally known as Bradley Field.

Fighter Training and Air WACs Support

Among the units that trained at Bradley was the 56th Fighter Group of the Eighth Air Force, which compiled one of the most impressive records for enemy fighter kills in the war. Additionally, the 57th Fighter Group also trained at Bradley and, after arriving in Cairo, Egypt, in July of 1942, went on to fight in North Africa, Sicily, and the Italian mainland.

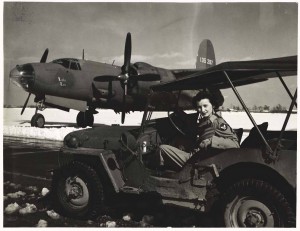

The operations at Bradley Airfield benefited from the support of a host of civilian and military personnel—among the most vital was the staff of the Women’s Army Corp. Known as Air WACs, these women did everything from driving vehicles, cooking, and performing clerical work, to developing photographs, making maps, and working as meteorological technicians. The demand for their services became so great that the Army began encouraging women to volunteer by promising them assignments close to home. Consequently, many of those who served as Air WACs at Bradley Field came from nearby Connecticut towns.

Bond Drive Raises Money for War Effort

Corporal Mary Alice Kadelak O’Brien, Women’s Army Corps, who is assigned as a driver to the Base Motor Pool at Bradley Field, 1944 – Connecticut State Library, State Archives, PG 048

In March of 1944, Army Air Force personnel and civilians completed one of the more impressive fundraising drives of the war bond effort. During a two-month period, personnel at Bradley Field attempted to raise enough money for the Army to purchase a $75,000 fighter plane. During this push, participation in the bond drive payroll savings plan at the base increased from 32% of the staff to 55%, with the average employee agreeing to a deduction of over 13% of their paycheck for war bond purchases. During the course of the drive, the personnel stationed at Bradley Field raised $89,450.

The Air Base Becomes a POW Camp

In October of that year, Bradley Field took on a new and entirely different role in the war effort. In addition to training pilots, the air base began serving as a camp for German POWs. Bradley personnel constructed a four-acre enclosure, isolated from the rest of the base, to house the growing number of surrendering German soldiers in the waning months of the war. The enclosure included a barracks, mess hall, hospital, recreation and study hall, and a supply office.

German POWs repairing fence, Bradley Field, 1944 – Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library and Connecticut History Illustrated

May of 1945 saw Bradley’s role change once again. Colonel H. E. Johnson, the airfield’s commander, announced that the Army intended to use Bradley Field as redeployment center for troops returning from Europe and headed to the Pacific. Redeployment efforts started on May 22, 1945, and over the next 12 weeks, 3,456 Liberators, Flying Fortresses, and transport planes delivered 58,563 military personnel to Bradley Field. Bradley staff gave soldiers medical exams, updated their personnel records, and processed any past-due paychecks owed to the returning men. Most of the soldiers then left Bradley on furlough until they received their next assignment.

The Army officially deactivated Bradley Field at the end of the war in 1945. In 1947, it became home to the Connecticut Air National Guard, but the airfield’s location, ideally situated between Boston and New York and away from areas of coastal fog, made it ideal for use as a commercial airport.