By Richard DeLuca

From its beginnings—as Dutch traders came up from New Amsterdam and English colonists came down from Massachusetts Bay—Connecticut’s position between New York and Boston has played an important role in the transportation history of the state and the region. Starting with the establishment of the King’s “best highway” in 1673, three chief routes developed through colonial Connecticut: the upper post road through New Haven, Hartford and Springfield; the lower post road, running east from New Haven to New London and Providence; and the middle route, which ran diagonally across eastern Connecticut from Hartford to Boston. These New York-to-Boston connectors, which we refer to today as I-95, I-91, and I-84, remain the three-pronged spine of overland transportation in Connecticut.

Woodcut of a postal rider – National Archives

An Intercolonial Network

Following the English capture of New York in 1664, an attempt was made to improve communication between New York and the English colonies in New England. On January 22, 1673, America’s first post rider left New York City carrying “two port-mantles crammed with letters, sundry goods and bags.” The rider headed to New Haven and Hartford, then on to Springfield, Worcester and Boston, where he arrived after two weeks, having covered a distance of 250 miles.

A royal charter in 1691 revitalized postal service throughout the English colonies in North America along a route that extended from Baltimore to Portsmouth, Maine. As part of this extended service, the post from New York to Boston passed through Connecticut along a shoreline route that ran from New Haven through Saybrook to Providence, Rhode Island, thereby establishing a second major travel corridor across Connecticut. Service now left New York once each week in summer (every other week in winter) and followed the lower road as far as Saybrook, where the New York rider exchanged mail bags with the rider who had come down from Boston via Providence.

By the 1690s, as new towns were settled in northeastern Connecticut, a third or middle post road was opened through the colony. This route left the upper post road at Hartford to run diagonally across the Windham Hills through Bolton, Tolland, and Woodstock, and then on to Boston. Though the exact path of the middle post road is debated, its existence is attested to by Benjamin Wadsworth, who traveled along it in 1694 on a trip from Albany to Boston. Leaving Hartford, Wadsworth and his companions encountered a road that was “very rocky, bushy, in many places miry; but tho our road was bad and long, being counted about 50 miles, yet we came to Woodstock about 8 of ye clock” in the evening.

Milestones Mark Distance—and the Colony’s Growth

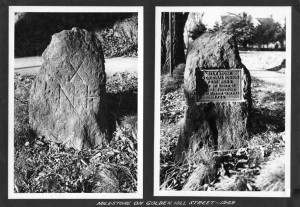

Milestone Marker on Golden Hill Street, Milford, by order of Benjamin Franklin, 1735 – Milford Public Library and the Treasures of Connecticut Libraries

As the Deputy Postmaster of the English colonies, Benjamin Franklin traveled the lower post road through Connecticut in the summer of 1753 with the goal of standardizing postal rates based on distance. Franklin and his assistants drove the road in a carriage equipped with an odometer and placed stone markers at mile points along the route. Soon after, the General Assembly of Connecticut ordered all towns located on any post route to erect stone markers, at least two feet high by the side of the road to indicate the distance to the nearest county seat. Signposts were also erected wherever roads diverged to guide travelers. This concern for milestones and signposts was a clear indication that travel and commerce were on the rise as the population of the colony grew.

In 1773, Hugh Finlay, the surveyor of all the King’s highways in North America, traveled through Connecticut as part of an inspection tour of postal operations in New England. Traveling from Newport, Rhode Island, to New London, Finlay noted that the portion of the lower post road in New London County was still in poor condition and “on the whole the most difficult and dangerous as any Boston Post Road Carved out Three Travel Routes through State in America.”

When he arrived in New London, Finlay was further inconvenienced when the post rider he expected to meet did not appear on schedule. He rightly suspected that John Herd, a Stamford resident and wizened old man of 72 who had carried the post for more than 40 years, was late due to business he conducted along the way for personal gain. As Finlay noted in his journal:

He does much business on the road on commission, he is a publick carrier, and loads his horse with merchandise for people living in [sic] his route; he receives cash, and carries money backwards and forwards, take’s care of return’d horses, and in short refuses no business however it may affect his speed at Post.

Despite Finlay’s disapproval, the financial transactions conducted by John Herd attest to the growing importance of the post routes to fostering market capitalism in Connecticut before the American Revolution.

Richard DeLuca is the author of Post Roads & Iron Horses: Transportation in Connecticut from Colonial Times to the Age of Steam, published by Wesleyan University Press in 2011.