By Nancy Finlay

The Roaring Twenties are often depicted as an era of hedonistic pleasure-seekers attending extravagant parties at exclusive private clubs and grand hotels. It was also an era when middle-class families began taking summer vacations, often staying for weeks at cottage communities or resorts at the shore or in the mountains.

There was, however, a dark side to this pleasant picture. Signs at many of the hotels read “Gentiles Only,” or, only a bit more subtly, “Clientele Carefully Selected.” Antisemitism was perhaps not as pervasive in Connecticut as it was in some states, but it was not entirely absent either. In 1922, resorts such as Sunny Field Farm in Farmington advertised in the Hartford Courant that it was “A Good Place to Spend Your Summer Vacation. Gentiles Only.” In Connecticut, as elsewhere, Jewish entrepreneurs reacted by establishing resorts specifically to cater to the Jewish population.

Vacation Resorts for a Jewish Clientele

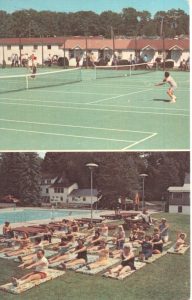

Tennis courts and daily calisthenics at Banner Lodge – Courtesy of Ken Simon

In 1922, Samuel Banner purchased a 135-acre farm in Moodus (a village in the town of East Haddam) and moved there with his wife and family. Banner, a Jew from Austria, had arrived in New York in 1899; his wife Rose, a Russian Jew, had immigrated in 1896. East Haddam and the neighboring town of Colchester were already home to large Jewish communities, primarily made up of recent immigrants from eastern Europe.

Shortly after acquiring the farm, Banner and his son Jack began welcoming vacationers there, much as Sunny Field Farm catered to vacationers in Farmington—but this time, Jews were not excluded. The Banners began developing the property as a resort, eventually expanding it to over four hundred acres. By 1933, they were able to offer swimming, boating, dancing, tennis, baseball, hot dog roasts, and chicken dinners.

From the 1930s to the 1970s, Banner Lodge was one of the most popular vacation destinations in Connecticut. At first promoted as a “vacation paradise for adults,” the lodge later expanded its program to include activities for families with children. It added a large theater in the 1940s and a nightclub in the 1950s. Featured performers included Joel Grey and Zero Mostel—Jack Banner’s first cousin, who appeared regularly at Banner Lodge while blacklisted during the Red Scare in the 1950s due to his supposed Communist sympathies. The lodge added an Olympic-sized swimming pool in 1954. In 1961, it first offered “new deluxe air-conditioned motel-style rooms with individual parking” as an option to the original rustic knotty pine cabins. Still later, the lodge upgraded with a day camp, an 18-hole golf course, and snowmobiling in the winter. The resort boasted two large dining rooms which could seat three hundred guests at a time, as well as a coffee shop and an extensive picnic area for outdoor barbecues.

Not Just for Vacationers

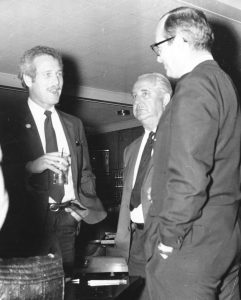

Jack Banner (center), Paul Newman (left), and Joe Duffy (right) – Courtesy of Ken Simon

In addition to vacationers, Banner Lodge became a popular destination for business outings. The employees of Hartford’s G. Fox Department Store held their annual outing at Banner Lodge in 1933. Other Jewish-run businesses and organizations, such as the Jewish War Veterans and the predominately Jewish Furriers’ Guild and Pharmacists’ Association, held encampments and conventions there, but the resort was popular with non-Jews as well. Over the years, all the big Hartford insurance companies and many other local businesses held outings there.

Banner Lodge was also the site of political gatherings and fund-raising events. Jack Banner was active in both local and state politics—a driving force behind the rescue and restoration of the Goodspeed Opera House in East Haddam and one-time chair of the State Development Committee. Abraham Ribicoff, John Dempsey, and Ella Grasso all frequented the lodge. (Dempsey’s son spent one summer at Banner Lodge working as a lifeguard); and Paul Newman hosted at least one fund-raising event there.

The Decline of Moodus Resorts

Guests eating a meal at picnic tables outside – Courtesy of Ken Simon

Banner Lodge had always catered primarily to Connecticut residents, attempting to adapt to their changing tastes. As more people acquired automobiles and air travel became more affordable, however, Americans began venturing farther afield on their vacations, and resorts such as Banner Lodge began to suffer.

Nevertheless, in June 1979, Jack Banner claimed that business was better than ever, with increased bookings for the summer season. Throughout the summer, he advertised aggressively in the Hartford Courant. He announced plans to convert some of the smaller cabins to vacation condominiums, to serve the increasing number of retirees who were spending winters in Florida and returning to Connecticut during the summer months. But in November, Banner died suddenly, and by the early 1980s, a New York development firm had bought Banner Lodge. They built some of the condos, but for decades the project suffered from poor management and financial problems. Today, the property is known as Banner Lodge Estates, touted as “New England’s most charming golf community,” where one can “live, golf, swim, and dine, just footsteps from one’s own home.”

Though Banner Lodge was the largest of the Moodus resorts, it was not the only resort in town. Others included the Grand View Resort, run by the Pivnick Family; Klar Crest, run by the Klar family; Orchard Mansion, operated by Herbert and Rose Krabatznick; and Ted Hilton’s Elm Camp, later known simply as Ted Hilton’s, then as the Frank Davis Resort, and finally as the Sunrise Resort. All are gone now, but live in on in the memories of those who attended outings or spent their summer vacations there.

Nancy Finlay grew up in Manchester, Connecticut. She has a BA from Smith College and an MFA and PhD from Princeton University. From 1998 to 2015, she was Curator of Graphics at the Connecticut Historical Society.