By Patrick J. Mahoney

At one time, Connecticut had two state capitol buildings and two capital cities: New Haven and Hartford. The General Assembly conducted business in both cities on a rotating schedule until 1875.

The origins of this unusual arrangement date back to 1701, when the General Court agreed to a proposed plan of having co-capitals. Connecticut achieved statehood in 1788 and adopted its constitution in 1818, but meetings of the General Court (which later became known as the General Assembly) alternated between the two cities starting in the early 18th century.

Thomas Hooker and Nicholas Davenport Found Two Capitals

From their origins during the colonial era, a sense of rivalry existed between the settlement at Hartford, formed in 1636 by followers of the Rev. Thomas Hooker, and the settlement of New Haven, formed in 1638 by the followers of Puritan minister, Rev. John Davenport, and a merchant-organizer, Theophilus Eaton.

Amos Doolittle, The Revd. John Devenport, ca. 1797, engraving, 1984.25.0. Portrait of the Reverend John Davenport – Connecticut Historical Society

The Hooker settlement initially assumed the indigenous name of the local river, Connecticut, as the name of its colony. Officials later changed it to Hartford, in honor of the town of Hertford, England. Similarly, the colony that emerged on Long Island Sound originally assumed the name Quinnipiack, after the local Native American tribe, but soon changed to the more English title of New Haven.

Although a royal charter (obtained in 1662) eventually joined the two settlements together in 1665, it was not until 1701 that the legislature decreed that New Haven and Hartford should be co-capitals. As such, the bi-yearly General Assembly meetings took place each May in Hartford, and each October in New Haven.

Hartford Becomes Connecticut’s Sole Capital

A debate began toward the end of the 1860s in Connecticut regarding the condition of the two statehouses used to hold the General Assembly meetings. A committee formed in 1869 to consider the effectiveness and future of the multi-capital system. Legislators decided that the capitol buildings of both New Haven and Hartford required structural repairs and additional meeting rooms. Furthermore, they deemed the practice of keeping separate books and files at the two locations as potentially wasteful and unnecessary.

After considering the future financial ramifications of maintaining two capitals, officials put the issue to a public vote in the form of a referendum to decide which city deserved to be Connecticut’s capital. New Haven supporters lobbied that, given the city’s booming industry and larger population, it made for a better choice. Conversely, Hartford attempted to gather votes by offering the state a plot of land, previously occupied by Trinity College, and a sum of $500,000 toward the construction of a new capitol building on the site. In the fall of 1873, Hartford emerged victorious, becoming Connecticut’s sole capital city, effective in 1875.

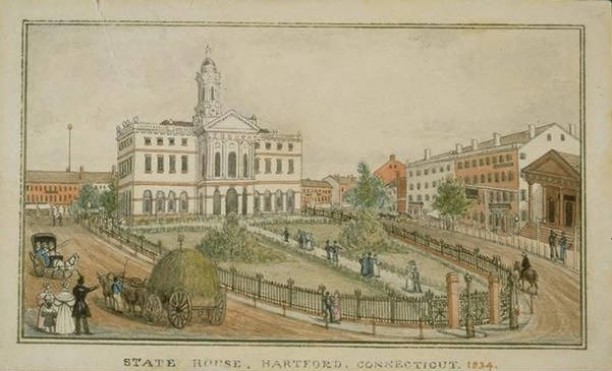

Edward Williams Clay, State House, Hartford, Connecticut. 1834. 1958.71.1 — Connecticut Historical Society

With the decision made to make Hartford the seat of government in the state, the General Assembly authorized a million-dollar project for the construction of a new capitol building. While the Assembly continued to meet in Hartford’s Old State House, designs poured in from contractors bidding on the relocation project. Ultimately, officials chose the design of New York-based architect Richard M. Upjohn. They also chose Hartford-based designer James G. Batterson (famous for his Civil War monument projects) to serve as the building contractor. Upon its completion in 1878, the marble and granite Gothic structure that overlooks Bushnell Park exceeded its initial budget by over a million dollars. The following year, the General Assembly met in the capitol building for the first time, beginning a new chapter in state politics.

Razing the New Haven Statehouse

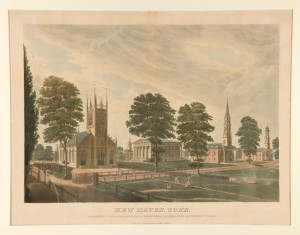

The last meeting in the New Haven statehouse occurred in 1874. In the decades that followed, officials decided to dismantle the former seat of the General Assembly, which at one point served as a focal point of the New Haven Town Green. Following a vote by the New Haven City Council in 1885, a sizable crowd of roughly 3,000 spectators witnessed the building’s ceremonial demolition.

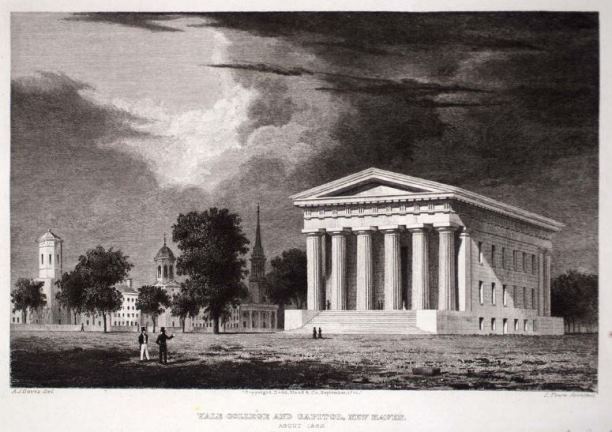

New Haven, Conn. Comprising a View of the Episcopal and Presbyterian Churches, Statehouse and Yale College, hand-colored engraving by Illman and Pilbrow, New York, 1831 – Yale University Art Gallery

Years later, it appeared that many citizens of New Haven regretted the decision to destroy the structure. A 1933 report in the Hartford Courant acknowledged a message posted in the New Haven Journal-Courier that retrospectively commended Hartford for its decision to preserve their Old State House following the move of the General Assembly to the new capitol building in 1879. The piece reflected, “New Haven did not realize the value of its structure and while it permitted three churches to retain their places on its common it caused the State House to be razed. Not, years afterward, New Haven residents realize that it is impossible to call back again the day that is past. There are many who will share the regret expressed by the New Haven Journal-Courier.” With the destruction of the building, the physical remnants of this unique period in the state’s history that connected Connecticut’s modern politics with its colonial past were cleared from New Haven’s historical landscape.

Patrick J. Mahoney is a Research Fellow in History & Culture at Drew University and former Fulbright scholar at the National University of Ireland Galway