By Mary M. Donohue for Connecticut Explored

“The Berlin Turnpike (1942) is our Via Sacra, and the Olympia Diner (1952) our Triumphal Arch.”

—Dennis Barone, in “Pike Pique: When Will the Berlin Turnpike Get the Respect it Deserves?,”

The Hartford Courant, January 18, 2004

Some have suggested that the 11-mile Berlin Turnpike be designated Connecticut’s next scenic road by dint of its appearance alone: the turnpike boasts a heady visual mix of neon, brand names, logos, and 1960s’ motel Modernism. Known as “Gasoline Alley” during the 1950s and heralded by some as sporting Connecticut’s best examples of “roadside architecture,” the road features an offbeat blend of vintage and contemporary gas stations, diners, miniature golf courses, motels, and bowling alleys, in addition to major retailers.

But the Berlin Turnpike’s eclectic beauty is not just skin deep. Since the appearance of the automobile at the beginning of the 20th century, the highway served as a model of what a modern road should be—paved, divided and four lanes wide, and offering motorists all the comforts, services, and amusements they would need in their travels (until the advent of the national interstate system reduced the concept of the ideal roadway to four or more lanes and no diversions, that is).

Olympia Diner, Berlin Turnpike, Newington – Photograph courtesy of Impropcat

Connecticut State Highway Department Paves Way to Improved Travel

Organized in 1895, the Connecticut State Highway Department (the third state highway department in the country) had a dynamic leader in James H. MacDonald. He served the state for more than 16 years as commissioner. MacDonald, Connecticut’s first state highway commissioner, was also a founding member of the American Association of State Highway Officials, formed in 1914. A leader at the state and federal level, MacDonald worked to improve Connecticut’s roads and build a network of “trunk” roads that connected urban centers. He may be rightly considered the “father” of the car-crazy Berlin Turnpike. His passion for the turnpike helped to set the stage for a border-to-border route that passed through Hartford.

As part of an effort to reduce highway congestion on Route 1 along the Connecticut shoreline, subsequent Commissioner John A. MacDonald (who served from 1923 to 1938) and his highway planners first focused on building the Merritt Parkway (completed in 1940) from the New York border to Milford, Connecticut. Designed with few traffic lights and flanked by landscaped vistas of native trees and shrubs, the Merritt Parkway also provided employment for construction workers during the Great Depression.

As retired highway engineer Larry Larned relates in Route 15: The Road to Hartford, the state next considered how to improve the drive from Milford through Hartford to the Massachusetts state line. The availability of toll revenues collected on the Merritt allowed the state legislature to propose constructing the Wilbur Cross Parkway from Milford to Union, Connecticut. When completed in 1949, the roadway allowed a traveler from New York to Massachusetts to seamlessly follow the Merritt and Wilbur Cross Parkways, the Berlin Turnpike, the Hartford Bypass, the Charter Oak Bridge, and the Wilbur Cross Highway (now part of Interstate 84).

Christening the Berlin Turnpike for Automobiles

Bicyclists in the 1880s had begun lobbying for better-surfaced roads to connect America’s towns and cities for bicycle touring. By 1900, they were joined by the new auto enthusiasts (or, as The Hartford Courant described them, “automobilists”). Originally part of the Hartford-New Haven Turnpike built in the late 18th century, the initial section of the Berlin Turnpike was dedicated in 1909 with speeches, a road race, and banquet. The Hartford Courant reported on October 7, 1909, “It is a long time since the opening of a stretch of state road, six miles in length, has been attended with ceremonies so elaborate…in all Connecticut there is no other half dozen miles of macadam of which the [highway commissioner James H. MacDonald] is more proud.” The winner of the dedication-day auto race was not the driver who went fastest but the one who stuck closest to what MacDonald (whose “pet scheme” The Courant called the turnpike) felt was the ideal safe speed for the road, covering the distance in 22 minutes. The Hartford Courant went on to comment on the tension between local use of the roadway and travelers’ needs: “The road…was built primarily for automobilists, and…will be of more benefit to them than to the residents along its way.”

The Berlin Turnpike was upgraded in 1920 at a cost of a half a million dollars when it became part of a continuous stretch of hard surface from the New York state line to the Massachusetts state line. The Hartford Courant announced “Berlin Turnpike Officially Open, Splendid Stretch of Concrete Ready for Football Crowd,” (a reference to the traffic generated by the Yale-Harvard football game in New Haven.) The road was now a concrete road almost 8 miles long (later improvements lengthened the Turnpike to what is now accepted as 11 miles). Before the improvements, The Hartford Courant had carried numerous articles about accidents and traffic congestion on the turnpike. James H. MacDonald noted that the turnpike had now been improved from “one of the worst stretches of road to among the best roadways in New England.” The newspaper commented that the only possible drawback to the splendid smooth roadbed might be a driver’s impulse to speed.

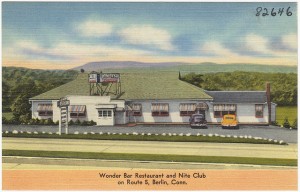

Wonder Bar Restaurant and Nite Club on route 5, ca. 1940s, Berlin – Boston Public Library, The Tichnor Brothers Collection

In the early 1940s, the state added two lanes to the turnpike, separating them from the existing ones with a median. The old turnpike became the southbound lanes, and the new lanes ran northbound, widening the turnpike from about 66 feet to about 200 feet. This improvement set the stage for explosive commercial growth along the turnpike after World War II. As the major thoroughfare from Boston to New Haven, by 1947 the turnpike saw on average about 11,000 cars daily. By 1953, that number had roughly tripled to more than 30,000. In 1950, the town of Wethersfield, at the northern end of the turnpike, experienced some of the fastest growth of any town in the state based on the value of new buildings for the years 1945 to 1949, spurred in part by the construction of gasoline stations and motels along the turnpike.

The turnpike earned its nickname “Gasoline Alley” in the post-War period. The 11-mile strip had at “at least 20 traffic signals” and, Larned notes, was “lined with 200 business establishments, including diners, dairy bars, hot dog stands, motels, drinking places, bowling alleys, dancing halls, petting zoos, and scores of gas stations.” One of the “great neon capitals of the Northeast,” the strip, with its more than 30 gas stations, became “the battleground for some of the Northeast’s most cutthroat price wars,” according to Chester Liebs in Main Street to Miracle Mile, American Roadside Architecture.

Roadside Architecture

For fans of streamlined diners and drive-in theaters and serious historians alike, roadside architecture has emerged as the study of the development of the roads, strips, and buildings designed specifically to accommodate the automobile traveler. Among the most studied roadways are the Lincoln Highway (1913), the first transcontinental road for autos from New York City to San Francisco, California, and Route 66 (1926), the “Mother Road” from Chicago to Los Angeles.

Connecticut’s Berlin Turnpike has the state’s highest concentration of notable car-culture buildings. Roadside historian John Margolies described how he came to his profession: “…the Berlin Turnpike…was lined with gas-war gas stations and honky-tonk diners and drive-ins…My parents’ generation thought these buildings were ugly and commercial and tacky, but I just saw them and swallowed them whole…” In Main Street to Miracle Mile, Liebs describes the appeal of the commercial strip as a “movie in the windshield”: ever-changing vistas in which businesses came fleetingly into view from behind the steering wheel.

Motel Modern: Spending the Night on the Berlin Turnpike

After World War I, car travelers often packed their own camping gear. This allowed them to stop wherever they wanted to set up camp for the evening and had the advantage of being inexpensive. Auto-camping became the rage and was adopted early by the Hartford Kiwanis Club. In 1921, the Kiwanis formally requested permission from the City of Hartford’s park commission to have Goodwin Park designated as a municipal campsite for auto tourists. The proposal had the support of the mayor and the Hartford Auto Club. The next mention of the auto camp in 1922 is in a Hartford Courant article whose headline reads “Auto Tourists’ Camping Park Now a Reality” but, instead of being located in Goodwin Park, the camp was constructed on the Berlin Turnpike (the exact location is now lost).

Many such municipally owned camps gave way to privately owned camps and ultimately to facilities offering small cabins. The “motor hotel” or motor court was born simultaneously with auto camps in the 1920s. The term “motel” can be traced to 1925, but the development of an adjoining series of rooms as individual units blossomed after World War II. The turnpike carried all types of travelers—families as well as businessmen. Clean, respectable, and brimming with amenities, the motels were often “mom and pop” family businesses.

Berlin Arms Motor Court, ca. 1940s, Berlin – Boston Public Library, The Tichnor Brothers Collection

Several types of classic mid-20th-century motels still exist on the Berlin Turnpike. The Kenilworth (1930) in Berlin is a large U-shaped tan brick building that follows the motel formula: a large sign at the road, a one-story building with individual doors to the units, parking at each unit door, and a centrally placed rental office. The building’s placement on the lot maximizes its presence on the street, with the wings located at the lot lines, giving the motorist every opportunity to spot it quickly. A color postcard from the 1950s shows a Modern-style interior with sleek, blonde furniture and modern bedspread and curtain fabrics.

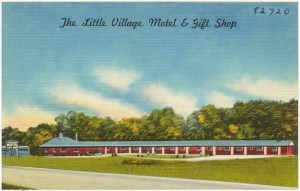

While trade magazines such as the Tourist Court Journal pushed the Modern look exemplified by the Kenilworth as a way to lure customers, other establishments took different approaches. The Little Village Motel and Gift Shop (1950), also in Berlin, for instance, aimed for a more picturesque, domestic look. The L-shaped hotel has a small, Colonial Revival-style office complete with roofline cupola. Since the roadside frontage is relatively narrow, the motel counts on the prominently placed office as well as the motel sign to help gain motorists’ attention. The suggestion of a safe and comfortable stay is further emphasized by the small scale of the motel and its landscaped grounds with ornamental fences, arbors, and benches. An early postcard also shows a diner next door, another plus for motorists.

The Little Village Motel & Gift Shop, ca. 1930-45 – Boston Public Library, The Tichnor Brothers Collection

The Forest Cabins & Motel (1940-50) in Berlin offered several types of overnight accommodations. A large brick building on the site is listed in city directories as a motel. Said to contain 15 rentable rooms, the building (not currently in use as lodging) is a traditional multi-story hotel with an office on the first floor. Adjacent to that building, the proprietor built eight single-story brick cabins. Designed as small efficiency units, the cabins are placed at the rear of the lot on a semi-circular road with a large lawn at the front. Tidy, well kept, and private, the cabins offered the tourist a quiet sanctuary. Liebs writes, “The little cabins offered individual housing in a minisuburban setting…enabling city dwellers to rent a freestanding, grass–surrounded dream cottage for a night or two.” The owner of the Forest Cabins & Motel also owned several gas stations, diners, and other motels along the turnpike. The Hartford Courant raved about the growth of the motel business in “More Motels” (1953). Using national statistics reported in The Wall Street Journal, it noted that there were 45,000 motels nationwide and 3,000 new motels opening that year. “One needs only to drive down the Berlin Turnpike,” The Courant wrote, “with its wide variety of splendid motels, to realize the money that has been invested in this industry and the popular appeal of these accommodations from the motoring public.”

As the motel business became more competitive, businesses had to offer more to the tourist. Large motel signs at the side of the road began to tout not only the price of a room but showers, tiled bathrooms, color television, swimming pools, playgrounds, or air conditioning. The Hartford Motel (1955) in Wethersfield, as depicted on an early postcard, was laid out as a long, linear strip behind a grassy lawn. Designed to incorporate a freestanding gas station as well as a restaurant, the motel offered the northbound traveler his “last chance” to rest, eat, or get gas before taking the bridge over the Connecticut River to the Wilbur Cross Highway east of Hartford.

Not everyone was happy with the commercial development at the northern end of the turnpike. In 1950, neighbors strenuously objected to a request to change the zoning along this portion from residential to business when a proposal for an $85,000 U-shaped motel in the Spanish style was proposed. But the Wethersfield zoning board approved the change, arguing that the fact that this was a throughway for traffic handling 28,000 cars a day clearly gave it much more commercial value than it would as a single-family residential zone.

The queen of all the motels on the turnpike is the Grantmoor Motor Lodge (1959) in Newington. The most architecturally commanding, it also offered the most complete package for the tourist. Billed as the “Gracious Grantmoor” when it first opened, it had a large restaurant and banquet hall (added in 1960; now the Sphinx Lodge), an L-shaped swimming pool with slide, and a golf course. Sleek enough for business travelers, the Grantmoor catered to leisure travelers, too, with golf for Dad and a pool for the kids. Executed in a truly Modern-style architectural design, it incorporates precast concrete “zigzags” at the roofline and originally had a railing with solid panels in primary colors. The restaurant has a dramatic “swooping” parabolic roofline. Bypassed by traffic once I-91 was built in 1965, the Grantmoor has more recently had a hard time attracting business. In the 1970s and 80s, it switched its marketing to emphasize a less family-oriented, more adult themed image, adding mirrors on the ceilings and installing plush shag carpeting.

Not Just For Passing Through

Ice cream stand along highway near Berlin, 1939

– Library Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

In addition to lodging, the turnpike has always offered plenty of leisure activities. At one time it was home to two drive-in movie theaters: the E.M. Loews Hartford Drive-in Theatre (1947) and the Berlin Drive-in (year not known). The drive-in, invented by Richard M. Hollingshead Jr. and patented in 1933, featured a semi-circular site plan with spaces for cars, a projection booth, and a multi-story movie screen. In an era bursting with families with young children, the drive-in allowed post-World War II parents to bring children (sometimes dressed in their pajamas), snacks, and drinks for a night out without hiring a babysitter. When it opened in 1947, the Hartford Drive-in charged 60¢ per adult; children were admitted free. Both of the drive-in theaters are gone, replaced by townhouses or big box stores.

Televised bowling tournaments in the 1950s raised that pastime’s visibility and created demand for bowling alleys across America. Three exist now: Bowl-O-Rama (1959) and T-bowl Duckpin (circa 1960), both in Newington, and Berlin Bowl (1960) in Berlin. The Bowl-O-Rama instituted a 24-hour schedule in 1960 and has been frequented by generations of college kids looking for early-morning fun.

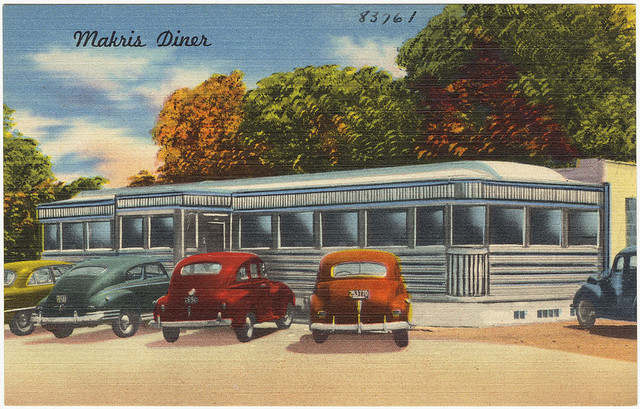

No visit to the Berlin Turnpike is complete without a stop at one of its two streamlined, silver diners: the Olympia Diner (circa 1950) in Newington at the southern end and the Makris Diner (circa 1951) in Wethersfield at the northern end. Both were manufactured by the Jerry O’Mahoney Company of New Jersey, and both remain remarkably intact both inside and out, retaining their sleek, linear “railroad-car” shape, each cloaked in shiny sheet metal with horizontal stripes.

Change on the Pike

When it opened in 1965, the new Interstate 91 siphoned much of the New Haven-to-Hartford traffic away from the Berlin Turnpike, leaving many establishments to fall on hard times. Unlike similar motels in popular shoreline areas such as Cape Cod, turnpike tourist cabins and motels struggled to attract business. Upkeep declined, swimming pools were filled in, and turnpike motels took on a reputation for “renting by the hour.” With that came a certain seediness: The local press has often made note of prostitution in the area and, as recently as 2009, the Town of Berlin struggled to close a VIP adult merchandise business; that effort succeeded, at least for the time being.

Yet many of the older businesses continue to hang in there. By the 1980s, shopping strips were built along the turnpike and by the 1990s fast food chains began to appear. The lodging business has continued to thrive, even as the ethnicity of ownership shifted. In the 1940s and ‘50s, Lithuanian immigrants were buying small motels on the turnpike. By 1992, American Asian Indians owned 40% of America’s motels that had fewer than 150 rooms; Asian Indians owned at least five of the turnpike’s motels that year. For both of these immigrant groups, the appeal of the small motel was the same as for the original owners: they could be run with hard work as family businesses. Many of the small motels were transformed into units that could be rented by the week or month, accommodating temporary workers or low-income lodgers. And in 2002, the turnpike’s first franchised lodging chain, Best Western, built a new 53-room motel, replacing the picturesque Red Cedars Motel.

Though the Berlin Turnpike is now populated by many “big box” stores such as Wal-Mart and Target and by the grand headquarters of the Connecticut Department of Transportation, the discriminating roadside historian will still find many examples of buildings from the 1940s to the 1960s. Maybe these will survive long enough to be discovered by the next generation of devotees and historic preservationists. Despite the changes over time, James H. MacDonald would be very satisfied that his model highway of 1909 has served the motoring public well.

Mary M. Donohue, the Assistant Publisher of Connecticut Explored, is an architectural historian and former executive director of the Manchester Historical Society.

© Connecticut Explored. All rights reserved. This article originally appeared in Connecticut Explored (formerly Hog River Journal) Vol. 8/ No. 1, Winter 2009/2010.

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.