By Steve Thornton

Can a movie change history? The Birth of a Nation did. The original 1915 film fomented racial bigotry and consciously distorted the history of the post-Civil War era.

D. W. Griffith’s silent movie extravaganza was a technical marvel and a historic travesty. The entire second act portrays its African American characters as boorish fools or scheming sex fiends. After its initial release, hundreds of thousands of people flocked to movie houses to pay as much as $45.00 a ticket (in today’s dollars) for the three-hour spectacle. It did more than any other medium to convince the white public that Reconstruction was a swindle and a crime against white Southerners. Only months after the movie’s nationwide premiere, the Ku Klux Klan—defunct since the 19th century—reorganized in the state of Georgia.

Birth of a Nation Comes to Hartford

It all started with The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan, a novel by Thomas F. Dixon Jr. published in 1905. No sooner was the book obtained by the Hartford Public Library than anonymous readers wrote “slurs upon the Negro” in the page margins, reported Reverend W. A. Harrod of the Shiloh Baptist Church. Worse yet, an effigy had been set ablaze and thrown on Rev. Harrod’s porch while the offenders yelled “Lynch him!”

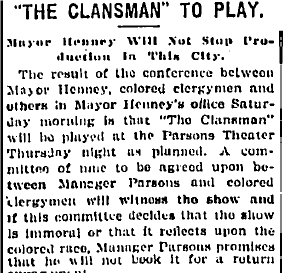

Newspaper article announcing Mayor William Henney’s decision to allow The Clansman to play in Hartford. The Hartford Courant, December 10, 1906.

Harrod was one of four African American clergymen who met with Hartford Mayor William F. Henney to express their concern when The Clansman became a hit stage play bound for Hartford. The production was due to open at the Parsons Theater in December of 1906.

After Henney proved reluctant to take action, physician and reformer Dr. Patrick Henry Clay Arms pointed out the hypocrisy of his decision. Arms argued that a play like George Bernard Shaw’s “scandalous” Mrs. Warren’s Profession (which met with controversy in New York and London) would be excluded on moral grounds, and, consequently, the same standard should apply to The Clansman.

After a second Hartford protest by a growing number of black and white clergy, Mayor Henney promised to travel to Manhattan and see the play for himself. He watched a performance on December 5, 1906. When he returned to Hartford, the mayor admitted there were “some uncomplimentary allusions to the negro that were liberally applauded.” Ultimately, though, Henney believed there was nothing “immoral or objectionable” to the play’s content. The show premiered as scheduled at Parson’s Theater.

Rebirth of The Clansman

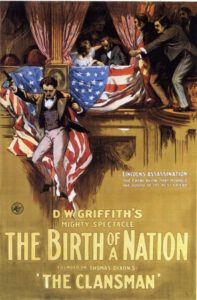

The Clansman proved so popular with white audiences that in 1915 it became the now-infamous movie by D. W. Griffith and retitled The Birth of a Nation. In September, Rev. Walter Gay, representing a group of Hartford residents who opposed the film, called on Mayor Joseph Lawler. Rev. Richard R. Ball told the mayor that The Birth of a Nation was “a gross injustice to the negro [that] breeds social strife.”

Color poster of the movie ”Birth of a Nation,” circa 1915 – Public Domain Image

The pastor of St. Paul’s Methodist Church, John E. Zeiter, then joined the chorus of protests when he denounced the movie from his pulpit. His address was not just a critique of the film, it was an insightful analysis of Reconstruction and the rise of southern Jim Crow laws. The minister seemed to have a deep understanding of the contribution African Americans had been making to the United States, despite centuries of crippling slavery. “The American negro owes this nation nothing but loyalty and citizenship—and in all other things the nation is his debtor,” Zeiter proclaimed.

In spite of these objections, the film played to sold-out Hartford audiences. Forty thousand people reportedly saw it in Bridgeport in its first week. The movie house projected the film twice a day, with special added holiday performances. No doubt, President Woodrow Wilson’s hosting of a private viewing in the White House helped give the film respectability in many proponents eyes.

Following a successful run of the film, the Palace Theatre returned to its normal vaudeville fare, which included Lasky’s Darktown Revue and its twelve “ebony entertainers.” Birth then returned for another Hartford run in 1916.

“Patriotic Suppresion”

It was not until 1919, however, that public officials took any significant action against The Birth of a Nation. After some 350,000 African American soldiers returned from the battlefields of the First World War, the black community began finding its political voice and challenging white supremacy at every level. It was around this time that those in positions of authority proposed censorship of The Birth of a Nation. In one such instance, The Hartford Americanization Committee asked Mayor Richard J. Kinsella to stop an upcoming 1919 run of the film at the Empire Theater and Kinsella agreed. “I was requested by the Americanization committee to suppress it,” the mayor told a reporter. “This is a very inopportune time for showing such a picture. I don’t think such a subject should be given publicity at this time.” Nearly one hundred years later, however, The Birth of Nation reappeared in Hartford theaters, but this time in the form of a 2016 film intended to re-envision the story of Nat Turner’s 1831 slave rebellion in Virginia.

Steve Thornton is a retired union organizer who writes for the Shoeleather History Project