Last Updated: January 7, 2025

By Todd Jones

Midway through the Civil War, Connecticut created the state’s first African American regiment, the 29th Connecticut Colored Infantry Regiment. Fighting bravely for the final year of the war, the regiment won many important battles and became one of the first Union regiments to march through the Confederate capital of Richmond. With its respectable service, the 29th Connecticut demonstrated the merits and justification for racial equality and freedom in Connecticut. The regiment, established late in 1863, was honorably discharged in November 1865.

Union Belatedly Allows African American Enlistment

The first two years of the Civil War had claimed the lives of tens of thousands of Americans, and the Union army was running very short on manpower. A military draft soon became necessary and proved incredibly unpopular. The draft, however, excluded thousands of African American men who were eager to fight but not allowed to serve because of their race. In July 1862, the United States government finally allowed African Americans to enlist, but only in separate Black regiments. In May 1863, the United States War Department created the Bureau of Colored Troops to manage the increasing numbers of Black volunteers.

Throughout the war, President Abraham Lincoln depended on individual states to recruit regiments and send them to the battlefield. Each regiment generally had one thousand men divided into ten companies. In November 1863, Connecticut’s governor and legislature decided African Americans would make up the 29th Regiment Connecticut Volunteers.

Through the remaining months of 1863, African American men from across the state poured into the training camp in the Fair Haven neighborhood of New Haven. By January 1864, the 29th Regiment Connecticut Volunteers was full. More men than expected showed up at the training camp and instead of turning them away, the state created the 30th Regiment Connecticut Volunteers. Before this new regiment filled, though, an impatient United States government, desperate for troops, took the men and combined them with soldiers from other states to form the 31st United States Colored Infantry Regiment.

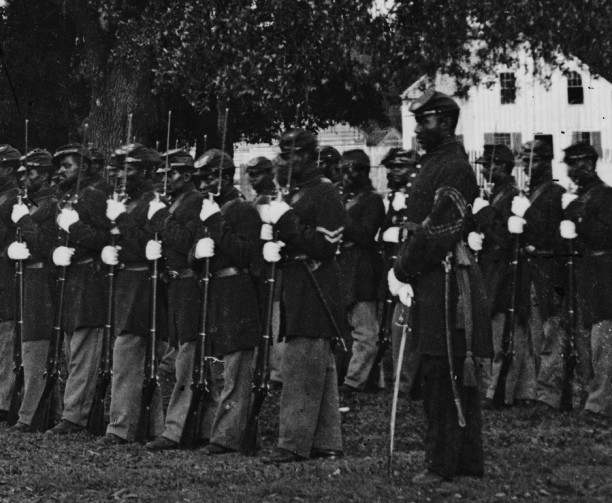

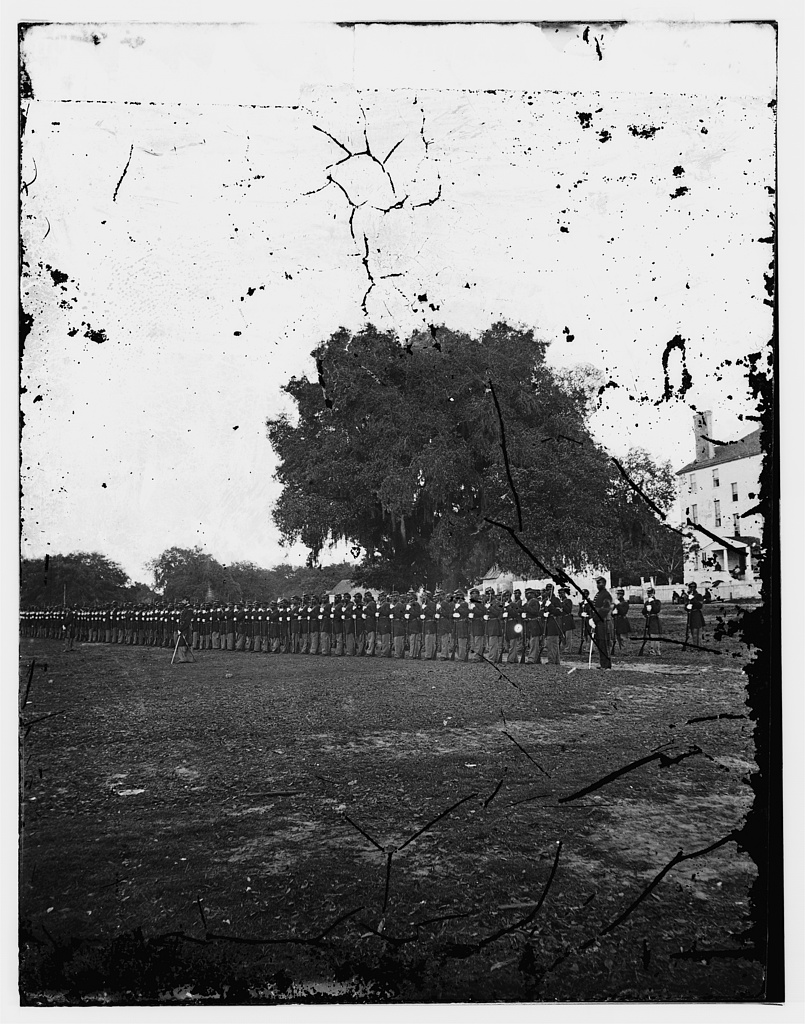

29th Regiment Connecticut Volunteers, Beaufort, South Carolina – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. Used through Public Domain.

The 29th Heads into Battle

The new recruits of the 29th Connecticut spent the next several weeks training in New Haven. In March 1864, the men paraded through the streets of New Haven and, according to soldier J.J. Hill, “white and colored ladies and gentlemen grasped me by the hand, with tears streaming down their cheeks…expressing the hope that we might have a safe return.” One of the recruits, Alexander Newton, recorded his time with the 29th Connecticut Volunteers which he later published as a memoir in 1910.

Despite African American participation in other American wars, many white Americans were uncomfortable with the idea of armed Black regiments. Despite troop segregation, the army generally appointed white men to lead United States Colored Troops, including Connecticut’s regiments. With Colonel William B. Wooster of Derby as the 29th Regiment’s leader, the men boarded a steamship bound for the South Carolina coast.

Sent to Virginia in the summer of 1864, the 29th Connecticut fought many small battles when Union and Confederate armies were locked in a siege between Richmond and Petersburg. During one of those battles, Newton fearfully remembered “a twenty-pound cannon ball coming towards me…through the smoke. It looked like it had been sent especially for me.” In September 1864, the 29th Connecticut helped take Fort Harrison, located less than ten miles from the Confederate capital in Richmond. On October 13, the regiment participated in a scouting mission which led to the Battle of the Darbytown Road, and two weeks later the men pushed the Confederate army back at the Battle of Kell House.

Bringing the Battle to an End

In April 1865, the Confederate line finally broke, and Richmond was evacuated. The 29th took part in the last attacks to empty the Confederate defensive trenches. Men of the 29th Regiment were among the first Union soldiers to march triumphantly through the streets of Richmond. Despite the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia in Appomattox, Virginia on April 9, the 29th Connecticut Regiment was sent to Brownville, Texas in June.

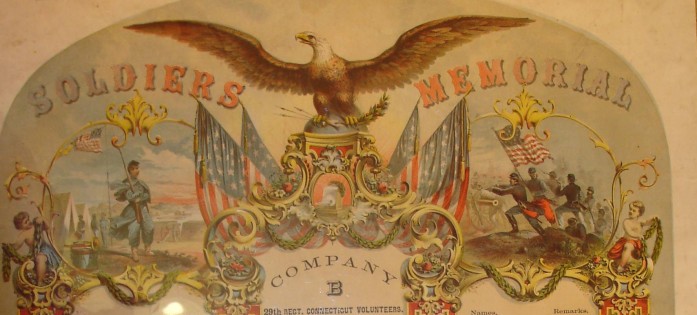

Image of Soldiers Memorial, Company B, 29th Regiment, Connecticut Volunteers – State Archives, Connecticut State Library. Used through Public Domain.

The 29th Connecticut mustered out in October 1865 and were honorably discharged on November 25. During a celebration, Governor William Buckingham thanked the men for their service and noted that “…although Connecticut now denies you privileges which it grants to others…the voice of a majority of liberty-loving freemen will be heard demanding for you every right and every privilege.”

Today, there is a monument to the 29th Regiment in Criscuolo Park in New Haven. Dedicated in 2008, the monument and its history of the 29th Connecticut Colored Infantry Regiment is part of Connecticut’s Freedom Trail.

Todd Jones, a life-long resident of the Nutmeg State, holds a graduate degree in Public History from Central Connecticut State University and is a Historic Preservation Specialist for the US government.

This article has been updated, learn more about content updating on ConnecticutHistory.org here.