By Mary Daly

“No persons of any race except the white race shall use or occupy any building on any lot except that this covenant shall not prevent occupancy by domestic servants of a different race employed by an owner or tenant.” This language, taken directly from a property deed dated June 10, 1940, in West Hartford’s High Ledge Homes Development, appeared in property deeds in five neighborhoods during the 1940s in West Hartford. In some places in Connecticut such barriers appeared even earlier.

These restrictive covenants, along with ones that may have existed in other Northern states, were implemented in order to prevent minorities from moving into white suburban neighborhoods. Real estate developers, homeowners, and neighborhood associations wrote these restrictions, called housing covenants, for their developments. Discriminatory covenants excluded certain groups from housing areas not only in Connecticut but throughout the northern United States as well.

Population Shift Sparks Unfair Realty Practices

The Great Migration of black people from the rural South to work in industrial factories in the North increased the minority population in Hartford beginning in the 1920s. Housing areas became a commodity that white people wanted to protect. In 1937, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) issued a map rating Hartford’s neighborhoods on a scale from A to D based on the perceived risk of mortgage defaults in each community. The HOLC labeled areas with a high concentration of minorities as riskier; these received a D rating, which was color coded as red on the map. Even a small number of minority families living in an area often resulted in it receiving a C rating. This map vividly documents how the racial composition of a neighborhood influenced the values of homes in the area.

This process—called redlining—exposed the deep concern many whites had about minorities moving into their neighborhoods. The influx of black people into the North and the redlining process contributed to “white flight” into the suburbs of Hartford starting in the 1940s. Real estate agencies and homeowners, concerned about black neighbors causing a decline in property values in their new white suburban enclaves, wrote housing covenants into their property deeds. Due to these covenants, black people were nearly eliminated from the suburban housing market during the 1940s.

Shelley v. Kraemer Limits Power of Restrictive Covenants

In 1948, restrictive housing covenants were deemed unenforceable by law in the Supreme Court case Shelley v. Kraemer on the grounds that such restrictions violated the 14th Amendment, which calls for equal treatment under the law for all citizens of the United States. This ruling did not, however, find the covenants themselves to be illegal. Therefore, some private parties still abided by the restrictive covenants in property deeds, even though they could not be enforced when taken to court. In many predominantly white areas of Connecticut, such as New Canaan, for example, “gentlemen’s agreements” not to sell homes to black people, Jews, or other minorities allowed discrimination to quietly persist. The Fair Housing Act of 1968 did much to discourage continuations of these practices.

Documenting a History of Discrimination

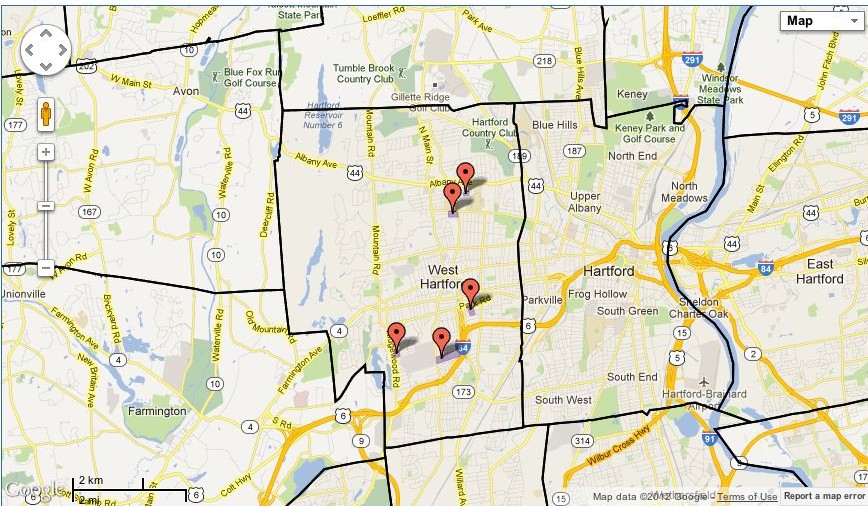

Since it is still legal to have these racially restrictive covenants in property deeds, some still remain in housing deeds in West Hartford. Such clauses have been documented for five areas, including the High Ledge Homes Development, by On The Line, a public history web-book by Trinity College professor Jack Dougherty. As part of this effort, The Cities, Suburbs and Schools Project, a collaborative effort involving Trinity faculty and students as well as community members, interviewed citizens of West Hartford in 2011. They asked residents living in homes with property deeds that included race restrictive covenants their thoughts on the matter. Younger, new residents of the area were alarmed to learn that they existed. “It’s not something I would have expected in Connecticut…,” said one. “I grew up believing that [overt racism] was in the South.” Those who had lived in their neighborhoods for a long time were less surprised. One woman reported knowing of the covenant when she purchased her home in 1970. These covenants are more than artifacts of an earlier time. They have shaped the present-day nature of communities across Connecticut.

Mary Daly, of Madison, Wisconsin, and a student at Trinity College in Hartford during the 2012-13 academic year, is majoring in Urban Studies with a minor in Latin American Studies.