By Gregg Mangan

The story of New-Gate Prison in East Granby includes more than three centuries of history. Once a copper mine and notorious prison, it is now a famed tourist attraction and a national historic landmark. Frequently referred to as either New Gate or New-Gate, the site operated as a prison from 1773 to 1827 and could accommodate more than 100 prisoners in its caverns at any one time.

Connecticut Seeks to Imprison and Reform Its Criminals

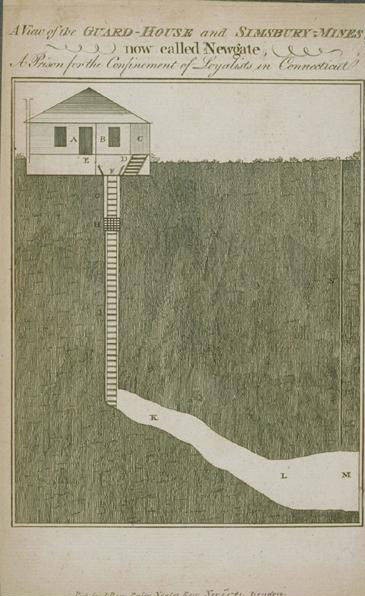

A view of the guard house and mines, East Granby, 1781 – Connecticut Historical Society

The area that would become New-Gate Prison was still part of the town of Simsbury in 1705, when it was designated for mining copper ore. Sixty-four town residents became the mine’s proprietors and formed the first chartered copper mining company in America. They used the mine’s revenues to pay town expenses and hire a schoolmaster. The proprietors eventually leased their mining rights to speculators willing to pay a portion of the ore they mined as rent. By 1773, however, copper ore deposits became harder to find and mining profits disappeared.

The Connecticut General Assembly explored the idea of turning the mine’s labyrinth of caves and shafts into a prison. In Connecticut, as well as in the rest of the colonies, public views on capital and corporal punishment were changing. Before New-Gate opened, penalties for breaking the law included whipping, cropping of ears, or branding with a hot iron. As the public became more sensitive to the consequences of inflicting such pain and degradation on fellow human beings, they looked for alternative ways to punish law breakers. Connecticut wanted to use the Simsbury copper mine as a place to isolate prisoners from the rest of society and then reform them.

Colonel William Pitkin, Erastus Wolcott, and Captain Jonathan Humphrey visited the mines in May of 1773 and found two shafts, one 25-feet deep with a ladder attached to it and another 67-feet deep used for extracting the copper ore. Upon inspection, the men determined that by carving a 16-foot lodging room out of the rock near the first shaft they had the makings of a formidable prison. The colony purchased the remaining years of a mining lease from Captain James Holmes of Salisbury and installed an iron gate near the surface of the 25-foot shaft. New-Gate was ready for its first prisoner.

The Makings of a Prison

That prisoner, John Hinson, sentenced to 10 years for burglary, arrived on December 22, 1773. Hinson escaped 18 days later by a rope lowered to him down the larger, non-gated mine shaft. In the years that followed, officials at New-Gate oversaw numerous improvements to the site in attempts to improve both the security and the economic viability of the prison.

One of these improvements involved the stationing of at least two guards to watch the prison at night. During this time, New-Gate not only housed thieves, counterfeiters, and murderers but Tories (a label given to those sympathetic to the British cause during the Revolutionary War) as well. Connecticut’s Council of Safety feared that the addition of Tories to New-Gate exacerbated an already uneasy situation that existed there. Some historians have theorized that the poor treatment Tories received at New-Gate may have provided a pretext for the ill treatment of American prisoners aboard British prison ships in the waters off New York City later in the war.

In 1781, prison officials erected a picket fence encompassing an area of approximately 187 by 160 feet and then replaced by a wooden palisade in 1790. They built a 12-foot-high stone wall in 1802 in the continuing effort to keep prisoners from escaping into the nearly five wooded acres that surrounded the prison.

Inside the fence, New-Gate grew into a bustling prison community. The prison built a guardhouse over the laddered mine shaft, which was complemented by a series of additions to the prison complex over the next several decades. On the north side of the yard, they established a nail and cooper’s shop. (A cooper was a craftsman who made and repaired wooden vessels, such as barrels, casks, and buckets.) Across the yard on the south side were a wagon and machine shop, a shoe shop, storeroom, kitchen, and chapel. In 1824, the prison erected a four-story building containing offices, a treadmill, granary, a mess hall, and cells for 50 prisoners. These improvements intended to keep prisoners secure and employed making commercial products to help offset prison operating expenses.

Daily Life on the Inside

At daylight, guards brought the prisoners up from the mines to the above-ground shops, where they worked until 4:00 p.m. When the prison first opened, the inmates mined copper, but New-Gate’s officials soon recognized the danger of putting digging tools in the hands of prisoners and instead put them to work making nails. By the time the prison shut down in 1827, the state had expanded its operations and employed inmates as shoemakers, coopers, blacksmiths, wagon makers, cooks, and basket makers. Those without trade skills dug stone, leveled the ground or made other improvements to the prison grounds. The most famous of the tasks assigned to the unskilled was operating the treadmill. Up to 22 men at a time powered this long, flanged wheel by climbing the paddles blades—a motion akin to walking up steps—in order to grind grain.

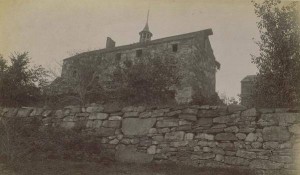

New-Gate Prison, East Granby, 1890s – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Illustrated

At night, guards ushered prisoners back into the mines where they devised plans for escape and shared tricks for making counterfeit money, false keys, and incendiary devices. The mines were a dreary, terrible-smelling place, where water constantly dripped from the surrounding rock. As former prisoner and master counterfeiter William Stuart recalled in his 1854 autobiography, “armies of fleas, lice, and bedbugs covered every inch of the floor which itself was covered in 5 inches of slippery, stinking filth.”

Despite moving the majority of prisoners to above-ground cells in 1824, New-Gate’s reputation drew a great deal of attention at the state capitol. The prison, originally thought to be escape-proof and a crime deterrent, had instead garnered a reputation for its lack of security. Prison reformers like Reverend Louis Dwight widely publicized the filthy conditions at New-Gate, and despite all its revenue-generating operations, the prison never managed to make a profit selling commercial goods. All of these factors led state officials to close the prison in 1827 and to move inmates to the newly constructed Wethersfield State Prison.

New Life as a Tourist Attraction

After its 54 years as a prison, New-Gate became the site of renewed attempts at mining and, briefly, a private residence where the owners provided candles and guided tours for curious visitors. By the 1870s, tourists and antiquarians interested in the nation’s and Connecticut’s colonial past referred to the property as “Old New-Gate.” After a fire in 1904 that destroyed much of the four-story cellblock, the former guardhouse was converted into a dance hall during the 1920s and ’30s. To entice visitors, the site boasted a variety of attractions, including a caged bear and cub, several antique cars, and a World War I tank. The state removed these features when it purchased and took over operation of the site in 1968. In 1973 the National Park Service designated New-Gate Prison a National Historic Landmark. Now called Old New-Gate Prison and Copper Mines, the property is administered by the Department of Economic and Community Development.

Gregg Mangan is an author and historian who holds a PhD in public history from Arizona State University.