By Robert Baron for Connecticut Explored

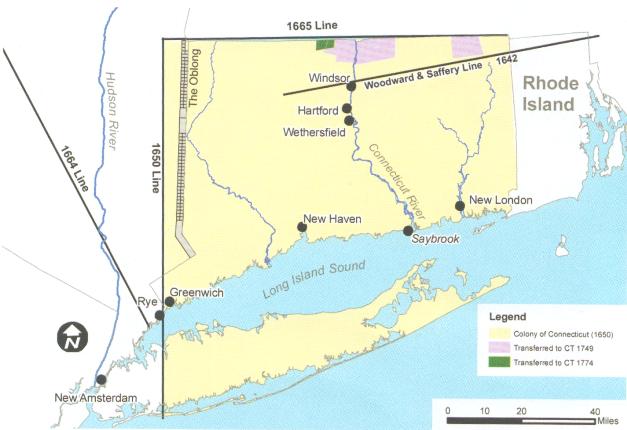

From the time of Connecticut’s charter in 1662 to the present, the state’s boundaries have posed many challenges for those of us who survey them. As State Historian Walter Woodward writes, the original charter received from King Charles II described Connecticut’s boundaries as including all lands west of Narragansett Bay, “south by the sea,” north by Massachusetts Plantation, and west by the Pacific Ocean and adjoining islands. For various reasons, the present map of Connecticut bears no resemblance to that description at all.

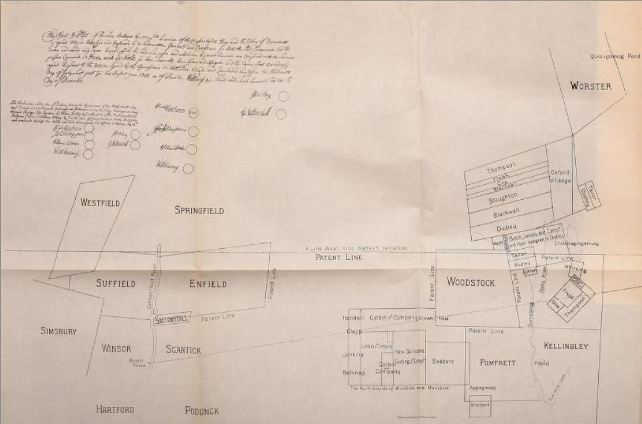

The troubles started with an errant survey of the state’s northern border performed by Nathaniel Woodward and Solomon Saffery of Massachusetts in 1642. These men were sailors, not surveyors. After determining where the Massachusetts line marking the border began, they sailed around Cape Cod and up the Connecticut River instead of surveying the line on foot as they should have. To compound matters, they mis-measured the latitude along the Connecticut River, putting the colony line about seven or eight miles south of the true line and placing Suffield, Enfield, and Woodstock in Massachusetts.

A Land Dispute between Connecticut and Massachusetts

Connecticut resurveyed the line in 1695. This more accurate survey was confirmed by surveyors from both colonies in 1702, yet Massachusetts denied the surveyors’ authority and insisted on maintaining the 1642 borders. In 1713, however, Massachusetts and Connecticut, to avoid England’s scrutiny, came to an agreement: Connecticut sold the disputed land to Massachusetts for 683 pounds, New England currency. The border towns were not party to this agreement and continued to petition Connecticut for annexation. (In almost every case along all Connecticut’s borders, towns preferred Connecticut for its lower taxes and the freedoms it afforded for local governing.) In 1749, the Connecticut Assembly decided to receive Suffield, Enfield, Somers, and Woodstock, having deemed that they fell within Connecticut’s charter limits and had been illegally sold, and those towns were returned to Connecticut. Only a sliver of land (north of the charter boundary) in Woodstock, known as the “Middlesex Gore,” was not annexed and remained Massachusetts territory.

The Chandler and Thaxter Survey of 1713 from The Boundary Disputes of Connecticut by Clarence Winthrop Bowen

Irregular Boundary Lines Settle Northern Border

Two other visible irregularities help define Connecticut’s northern line. The more prominent is known as the “Southwick Jog.” Southwick was a section of the older Massachusetts town of Westfield, though its limits fell south of the true colony line. Westfield had been settled long before Connecticut’s charter, and boundaries in this lightly settled western region of Massachusetts remained poorly defined. In 1801 Connecticut and Massachusetts came to an agreement: The portion of Southwick east of the Congamond Lakes went to Connecticut and became part of Suffield, and the western portion, still known as Southwick, went to Massachusetts. A second, less prominent, southerly deviation of the Connecticut Charter is at Enfield and Longmeadow. It is based on the original layouts of those towns, determined in part by the position of the Longmeadow River. In 1797, commissioners determined that the river had moved north, and a line was struck to approximate the original river location, creating the irregular line between Enfield and Longmeadow.

The last action to finally settle the Connecticut/Massachusetts border took place in 1826 and remedied a very small jog at the Union/Woodstock corner. From Southwick westward, there were virtually no significant border issues, presumably because that land was so lightly settled.

The State’s Other Borders

Portions of Connecticut’s western and southern boundaries also remained in play over the years. When the colonies of Saybrook, New Haven, and Connecticut merged in 1644, Connecticut claimed the eastern part of Long Island based on a patent granted to the Earl of Sterling that was mortgaged to George Fenwick (of Saybrook) and others. The Earl of Sterling’s patent hadn’t been confirmed by the king in the form of royal charter. The Duke of York bought the patent from the earl’s heirs and, upon the advent of the duke’s patent for New York, took all of Long Island.

In 1650, the colony of Connecticut and the Dutch who had settled New Amsterdam (now New York City) agreed that Connecticut’s western border would be set 50 Dutch miles west of the Connecticut River. This agreement is also known as the Treaty of Hartford. This agreement was never ratified, since England refused to acknowledge the validity of any Dutch claims to North America. (The Treaty of Breda in 1667 placed all of New York in England’s possession.)

New York’s patent of 1664 granted to the Duke of York claimed Long Island and all lands west of the Connecticut River. Due to some very astute political maneuvering by Connecticut officials, an agreement that was very generous was consummated that same year. Unfortunately, a new patent to the Duke of York in 1674 was granted that would negate this agreement—except that Connecticut refused to acknowledge it, relying instead on the 1664 agreement. Finally, in 1682 an agreement with New York (ratified in 1683) set the Connecticut/New York border 20 miles east of, and parallel to, the Hudson River. Connecticut also received the rectangular section of land east of the Byram River in Greenwich but had to give an equal amount of land back to New York along this western border, an area known as the “Oblong.”

Despite the provisions of the 1662 royal charter, Connecticut’s eastern boundary is nowhere near the Narragansett Bay. Connecticut’s Governor Winthrop and Rhode Island’s Roger Williams and John Clarke, the agents for that colony, were both in England at the same time attempting to get charters for their colonies from King Charles II. In 1664, Williams came back to New England while Clarke remained in England as Rhode Island’s agent. It is said that he wrote Rhode Island’s charter based on his discussions with Winthrop. Under their agreement, Connecticut would concede all of the lands from the Narragansett River to the Pawcatuck River; to the displeasure of the Connecticut General Assembly, Connecticut got little in return. (Making matters yet more confusing, the men agreed that the Pawcatuck would also be called the Narragansett River. Even today, the mouth of the Pawcatuck is also called “Little Narragansett Bay” on nautical charts.)

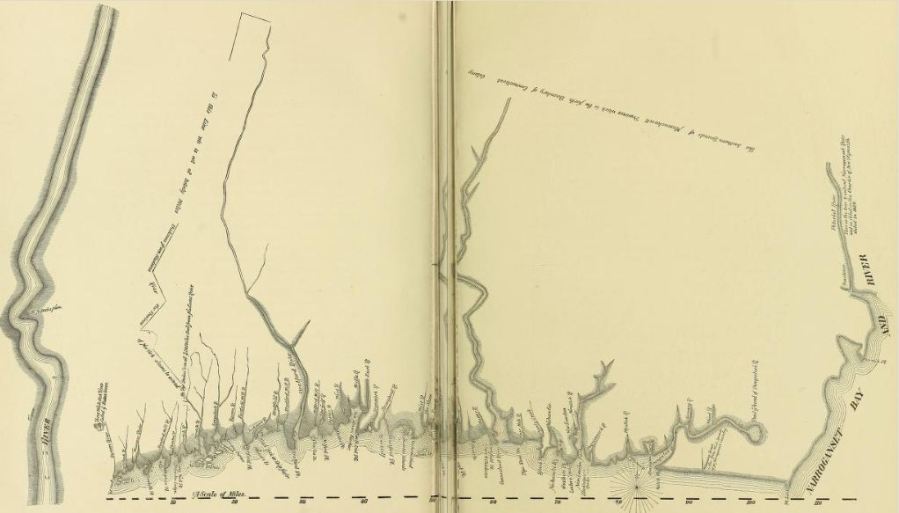

The Connecticut General Assembly rejected the Winthrop-Clarke agreement. In 1703, both states agreed that the boundary would run up the Pawcatuck River to the Ashaway River and then due north to Massachusetts, but the line was not surveyed. It wasn’t until 1839 that a joint survey was performed, and the line was finally ratified in 1840.

Massachusetts also claimed a portion of the lands within Connecticut’s charter (between the Mystic and Pawcatuck Rivers) as payment for assistance during the Pequot War. Lucky for us, Connecticut prevailed and kept that valuable piece of land.

A 20th-century Re-Survey

Eventually, the accuracy of the 1839 survey came into question as it was discovered that some of the monuments marking borders had been erected in significantly erroneous locations. In 1939, Connecticut performed a very accurate resurvey of the line. Joint commissioners appointed by both states to settle the question of accuracy then determined which boundary monuments to honor. A detailed report was prepared and signed by both commissioners in 1941.

Unfortunately, this revised line was never adopted by both states; the issue may have fallen to the wayside in the midst of World War II.

Contemporary Border Problems

In 2003, the dispute flared up again when two Connecticut towns performed surveys for new tax assessor mapping based on the 1840 agreement. The town leaders decided to levy Connecticut taxes on residents of Rhode Island based on what they called a “laser accurate” survey, and tempers flared. The original 1839 monuments (which had been accepted by the 1941 commissioners) don’t fall exactly on that line. Since the 1941 agreement was never ratified, only the 1840 agreement has true legal validity (despite its inaccuracy). Land surveyors are required to honor original, undisturbed monuments. Over the years, lands were sold and developed using the original monuments as being the true line. Because they are based on the line defined in 1840, those property boundaries don’t fall exactly where they should. Even though the 1840 line carries legal weight, it is an error not to honor the lines that everyone believes to be the true line.

Rhode Island and Connecticut officials agreed that the 1941 commission report should be honored. Connecticut law requires that its boundary markers be visited every 10 years and restored if they have been damaged or disturbed. Connecticut has replaced 11 broken or stolen monuments along this border. Connecticut and Rhode Island agreed to conduct a complete joint re-survey in 2004. But only the Connecticut Department of Transportation received its share of the required state funding. As monuments were known to be missing, Connecticut chose to go ahead with the survey on its own.

Robert Baron is the chief of surveys for the Connecticut Department of Transportation and serves on the board of directors of the Connecticut Association of Land Surveyors.

© Connecticut Explored. All rights reserved. This article originally appeared in Connecticut Explored (formerly Hog River Journal) Vol. 10/ No. 2, SPRING 2012.

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.