In February of 1889, the Connecticut General Assembly passed a bill making the first Monday of each September a legal holiday. Labor Day, an initiative of the labor movement, had been celebrated in various Connecticut towns in earlier years, but it was not until 1887 that states began making this tribute to workers’ economic and social worth a recognized holiday. It became a federal observance in 1894, with passage of the law coming after a period of nationwide clashes between workers and industry that had culminated in the deadly Pullman Strike in Illinois.

A Slow Start to Celebrations

The first celebration of Labor Day in Connecticut after the law’s passage was not as glorious as some in the labor movement had hoped. A parade of workers held in the capital city on September 2, 1889, started an hour late and, according to the Hartford Courant, drew a marching corps of “less than four hundred strong.” Speeches, dancing, and celebration followed the parade, which earned little praise from the keynote speaker, Edward King, a trade union activist and member of the New York City Central Labor Union. King declared that he would not flatter the local unions for what he deemed a poor turnout given the large number of wageworkers in the city. The Courant reported that he blamed “…the ‘dudes’ in the shops, who stand on the curbs and see the parade go by rather than march with the boys.” In his speech, King also urged the working women of Hartford to organize.

Other events marking the state’s first official Labor Day included a picnic in West Winsted attended by an estimated 3,000 people and factory closures in New Haven. Elsewhere, observers reported that the day passed without much notice.

Leisure Marks Tribute to Workers

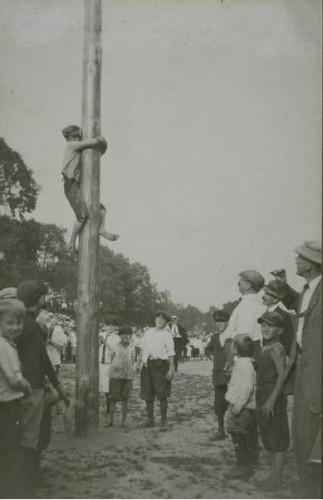

By the early 1900s, Labor Day had become a much grander affair and an occasion for family fun. In addition to a parade, Hartford boasted festivities in Colt Park. In 1913, for example, organizers of the Colt Park celebrations promised readers of the Hartford Courant “a program that will afford pleasure to everyone.” Attendees could picnic, dance to the music of military bands, choose from 15 baseball diamonds to watch or play the nation’s pastime, listen to speeches, and compete for prizes in athletic events. The latter included everything from a “50-yard dash for fat men of 200 pounds,” for which the victor would receive a $3.50 box of cigars, and a greased pole climb, with a promise of a $3.00 ham for those who successfully shimmied to the top.