By Ben Railton

In his creation of Hartford’s Chinese Educational Mission, Yung Wing drew from many core features of his own transnational Chinese American experience. And in their respective tragic but inspiring final American acts, Yung and the Mission reflect the worst and best of the Chinese Exclusion Act era.

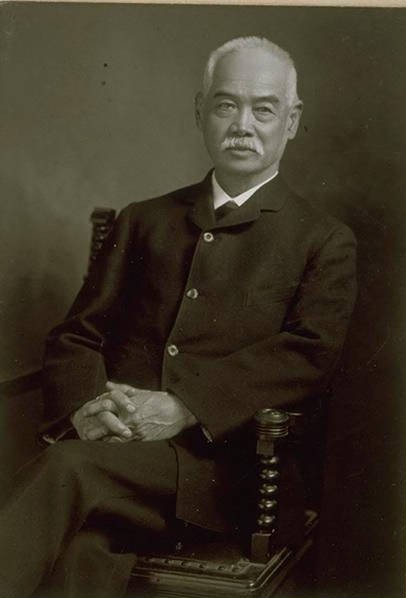

Yung Wing, Hartford, ca. 1900 – Connecticut Historical Society

Experiences as Chinese American Shape Yung’s Vision

In his memoir, My Life in China and America (1909), Yung notes that he first conceived of the Mission while turning down a group of church officials who hoped to fund his Yale education. The officials wanted Yung’s promise that he would return to China as a Christian missionary after graduation, but Yung believed that “the calling of a missionary is not the only sphere in life where one can do the most good in China or elsewhere.” He decided, “[I] might be obliged to create new conditions, if I found old ones were not favorable to any plan I might have.” One of the “new conditions” he went on to create became the Chinese Educational Mission, a program that brought young men from China to study in the United States.

Over the next two decades, Yung’s plan developed alongside his own experiences as a Chinese American. A core goal of the Mission, Yung wrote, was to help “the rising generation of China enjoy the same educational advantages that I had enjoyed,” both in New England preparatory schools and at universities like Yale. But there were other relevant elements as well. Yung volunteered for the Union Army during the Civil War (though his services were declined), and the Mission’s design included mandatory time at Annapolis and West Point for its students. He had become a US citizen in 1852 and later created a home with his wife, Avon’s Mary Kellogg, and their two young sons. And, he hoped to likewise see “the gradual but marked transformation of the students in their behavior and conduct as they grew in knowledge and stature under New England influence” while continuing their lessons in Chinese language and culture.

Anti-Chinese Sentiment in US Grows

Yung Wing’s wife, Mary Kellogg, at the time of their wedding, ca. 1875 – Thomas LaFargue Papers, 1873-1946: Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections (MASC), Washington State University Libraries

Yung and the 120 students who comprised the Mission when it opened in Hartford in 1872 represented a significantly more privileged community than many of their fellow Chinese immigrants. Those arrivals came to work in low-wage and dangerous jobs, whether in New York or on the Western railroads and lived in crowded Chinatown tenements in order to do so. They also endured being subjects of bigotry and scorn in their communities and the media. In contrast, Yung and the Mission students studied at some of the region’s foremost institutions, living with host families and in Ivy League dormitories. They did so with the support of the US and Chinese governments. Yet, when foreign relations shifted, Yung and the students were just as vulnerable and threatened as any of their fellow immigrants.

The event that officially ended the Mission was when the first prospective group of Annapolis and West Point attendees was refused entrance. Deeply offended, the Chinese government withdrew support for the Mission and ordered the students and Yung to return to China. The moment reflected the era’s broader and evolving histories of discrimination: the students were refused entrance due to the US government’s break from the Burlingame-Seward Treaty, the most overt of its series of moves toward the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. (The treaty contained several agreements that reinforced equality between the two nations; for example, it contained a provision that citizens of each country have reciprocal access to education and schooling when living within the other’s borders.) As Yung put it:

The race prejudice against the Chinese was so rampant and rank that not only my application for the students to gain entrance to Annapolis and West Point was treated with cold indifference and scornful hauteur, but the Burlingame Treaty of 1868 was, without the least provocation, and contrary to all diplomatic precedents and common decency, trampled underfoot unceremoniously and wantonly, and set aside as though no such treaty had ever existed, in order to make way for those acts of congressional discrimination against Chinese immigration which were pressed for immediate enactment.

Although drastically and even tragically affected by these events (Yung’s wife Mary, for example, died a few years later, her illness caused at least in part by the stress of the forced separations from Yung), both Yung and many of the students continued their inspiring transnational lives—lives that bridged Chinese and American cultures. Yung returned to America in 1902 to see his younger son graduate from Yale and, it seems, he remained in the country as an illegal immigrant, living with his sons and dying “at his home in Hartford” (per the New York Times obituary) in 1912. Students such as Chang Hon Yen likewise resisted both the Exclusion Act and the Chinese government and stayed in the US. Chang fought for the opportunity to pass the New York bar examination, became a practicing lawyer, and subsequently traveled to San Francisco to work on behalf of the Chinese American and immigrant communities there, among his many other accomplishments.

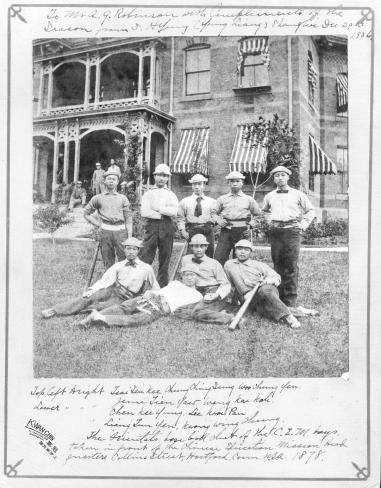

The “Orientals,” baseball club of the Chinese Education Mission boys, taken in front of the Chinese Educational Mission Headquarters, Collins Street, Hartford, 1878 – Thomas LaFargue Papers, 1873-1946: Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections (MASC), Washington State University Libraries

A Final Triumph

Even at their collective low point, in the immediate aftermath of the Mission’s closure, the students experienced, and in fact created, one more deeply inspiring transnational American moment. During their time in Connecticut, some of the students had formed a baseball team, known officially as the Orientals but usually referred to as the Celestials. The Celestials had considerable success on the local circuit and, by the time of the Mission’s closure, had developed a reputation as a talented team. With that closure, most of the students traveled to San Francisco to await a steamer back to China. Before the students’ departure from their new homeland, a local Oakland baseball team challenged the Celestials to a game. It’s impossible to know whether the challenge represented good sportsmanship or another aspect of the state’s and nation’s rising anti-Chinese fervor, an attempt to rise above the prejudice or an opportunity for athletic jingoism. In either case, at least according to student Wen Bing Chung, “the Oakland men imagined that they were going to have a walk-over with the Chinese.” But the team rose to this surreal occasion and the Celestials won their final game.

Chinese American and immigrant communities were, in this Exclusion Act era, fragile, always endangered, and subject to the worst of the nation’s xenophobia and bigotry. But as the students’ experiences and victories illustrate—and as Yung’s life and identity exemplify—19th-century Chinese Americans also comprised an evolving, transnational community that helped define the best of US history, culture, and ideals. Some of that community’s most inspiring moments, from Yung’s Avon marriage to his final years in Hartford, the Mission’s Hartford opening to the Celestials’ baseball games, also represent a powerful part of Connecticut history too important to be forgotten.

Ben Railton is Associate Professor of English and Coordinator of American Studies at Fitchburg State University in Massachusetts, and his most recent book is The Chinese Exclusion Act: What It Can Teach Us About America (Palgrave Pivot, 2013).