By Ellsworth S. Grant

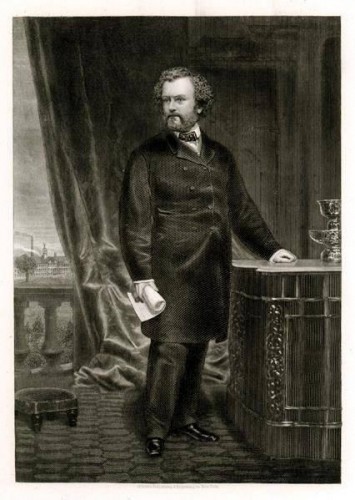

The funeral of Samuel Colt, America’s first great munitions maker, was spectacular—certainly the most spectacular ever seen in Hartford, Connecticut. It was like the last act of a grand opera, with music played by Colt’s own band of immigrant German craftsmen, supported by a silent chorus of bereaved townsfolk. Black bands on their left arms, Colt’s 1,500 workmen filed in pairs past the casket in the parlor of Armsmear, his mansion; next, followed his guard—Company A, 12th Regiment, Connecticut Volunteers—and the Putnam Phalanx in their brilliant Continental uniforms. Samuel Colt, who had been born July 19, 1814, passed away on January 10, 1862. His burial took place a few days later.

Armsmear, Wethersfield Avenue, Hartford – Connecticut Historical Society

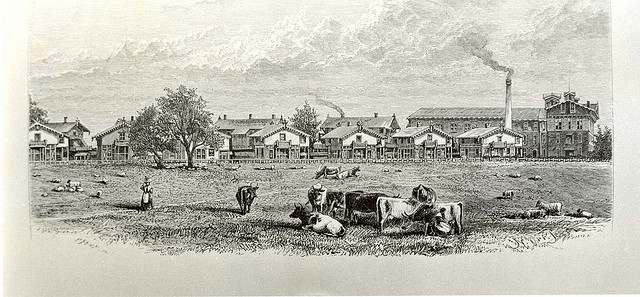

A half mile away the Colt Armory stood quiet—its hundreds of machines idle, the revolvers and rifles on its test range silent. Atop the long dike protecting Colt’s South Meadows development drooped the gray willows that furnished the raw material for his furniture factory. Beneath the dike a few skaters skimmed over the frozen Connecticut River. To the south, the complex of company houses was empty for the moment, as was the village specially built for his Potsdam willow workers.

On Armsmear’s spacious grounds snow covered the deer park, the artificial lake, the statuary, the orchard, the cornfields, and meadows as well as the fabulous greenhouses. At the stable, Mike Tracy, the Irish coachman, stood by Shamrock, the master’s aged, favorite horse, and scanned the long line of sleighs and the thousands of bareheaded onlookers jamming Wethersfield Avenue. After the simple Episcopal service, the workers formed two lines, through which the Phalanx solemnly marched with its drums muffled, color draped, and arms reversed. Behind them, eight pallbearers bore the coffin to the private graveyard near the lake.

A Life Rich in Controversy

Thus, on January 14, 1862, Colonel Samuel Colt was laid to rest. He was 47 and had died of an infection that may have been pneumonia. The most famous and the wealthiest inventor in the United States, he had dreamed an ambitious dream and had made it come true. Sam Colt had raced through a life rich in controversy and calamity and had left behind a public monument and a private mystery. The monument, locally, was the Colt Armory; in the world beyond, it was the Colt gun that was to help conquer the western and southern frontiers. The mystery concerned his family, whose entanglements included lawsuits, murder, suicide, and possibly bigamy and illegitimacy. Sam Colt’s short life had indeed been full.

Potsdam Village & Willow Ware Factory – Connecticut State Library, State Archives, PG 460, Colt Patent Fire Arms Manufacturing Company

The foremost mourner was the deceased’s calm and composed young widow, Elizabeth Colt, holding by the hand their three-year-old-son Caldwell, the only one of five children to survive infancy. Elizabeth was to become Hartford’s grande dame, and her elaborate memorials would ennoble Colt’s deeds at the same time that they would help conceal the shadows of his past. Her mother, her sister Hetty, and her brothers Richard and John Jarvis, both Colt officials, sat behind her. Richard, then the dependable head of Colt’s willow-furniture factory, would in a few years become the armory’s third president. Only the year before, the colonel had sent John to England to buy surplus guns and equipment.

The Famous Gather

Near the Jarvises sat Lydia Sigourney, Hartford’s aging, prolific “sweet poetess,” who had been Colt’s friend from his youth and who looked upon Elizabeth Colt as “one of the noblest characters, having borne, like true gold, the test of both prosperity and adversity.”

Four of the pallbearers had played major roles in Colt’s fortunes. They were Thomas H. Seymour, a former governor of Connecticut; Henry C. Deming, mayor of Hartford; Elisha K. Root, mechanical genius and head superintendent of the Colt Armory; and Horace Lord, whom Colt had lured away from the gun factory of Eli Whitney Jr. to become Root’s right-hand man.

And in the background, obscured by the Jarvises and the Colt cousins, was a handsome young man named Samuel Caldwell Colt. In the eyes of the world he was the colonel’s favorite nephew and the son of the convicted murderer John Colt, but according to local gossip he was really the illegitimate son of the colonel himself by a German mistress.

Entry by Ellsworth S. Grant; amended by Connecticut Humanities staff, 2011.