By Walter W. Woodward for Connecticut Explored

Of all the Connecticans who have left their mark in distant places, perhaps none made a more lasting—or more controversial—impression than Hiram Bingham III.

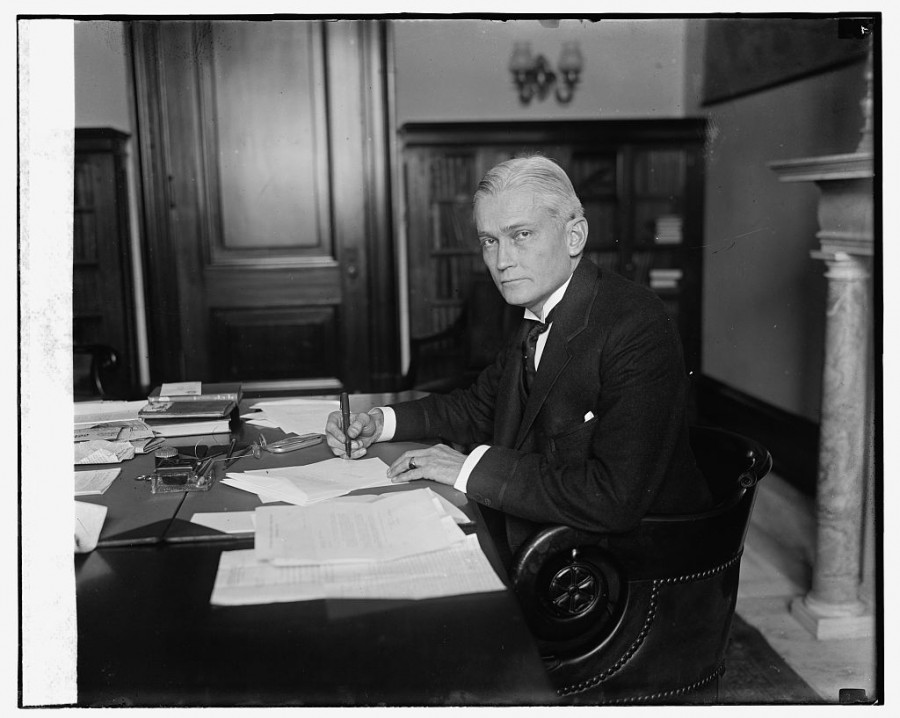

Born in 1875, this scion of two generations of New England missionaries to Hawaii accomplished much in his 81 years. He was an explorer, a best-selling author, an aeronautics authority, a Yale professor, and a politician who served as Connecticut’s lieutenant governor, governor, and United States senator. But the accomplishment for which Hiram Bingham III will always be most remembered—and criticized—is his scientific discovery of Machu Picchu, the “lost” city of the Incas, which produced a century of contention between Peru and Yale over repatriation of Bingham’s Inca artifacts.

Bingham “Discovers” Machu Picchu

His parents had intended for the handsome, Yale-educated, six-foot-four-inch-tall Bingham to follow in the family trade and do missionary work in China. His marriage in 1900 to Tiffany heiress Alfreda Mitchell, however, provided other, welcome options. Freed from the need to find a job, Bingham sought a PhD at Harvard in South American history, which led indirectly to his 1911 expedition to the Peruvian Andes. There, at nearly 8,000 feet, he came upon the thoroughly overgrown but locally known Inca architectural masterpiece. This 1911 “discovery,” and a 1912 return expedition to Machu Picchu financed by Yale and the National Geographic Society’s first archaeological grant, led to the transfer of 5,415 lots of artifacts, including the bones of about 173 individuals, to Yale for research. Equally significant were the more than 200 stunning photographs Bingham took of the “lost” city, which filled an entire issue of National Geographic in 1913 and made Machu Picchu and Bingham both international celebrities.

Controversy Surrounds Incan Artifacts

From the beginning, though, Bingham and his exploits drew criticism. Peru claimed ownership of the recovered artifacts even before they were transferred to Yale and almost immediately demanded that the university return them. Bingham himself was criticized for aggressive self-promotion, failing to acknowledge those whose information had helped him, and dodging the fact that the “lost” city had never really been lost. To his credit, Bingham never claimed to have been the first at Machu Picchu, only the first to understand its historic significance.

The bitterly contested artifacts dispute between Peru and Yale lasted nearly a 100 years. Following a November 2010 agreement, though, the return of the artifacts to Peru was completed in May 2012. The personal criticism Bingham received proved so strong that he quit exploring altogether in 1915, turning first to aviation and then to politics. He earned a pilot’s license in 1917, and as an army lieutenant colonel he commanded the Allies’ largest aviation training center in France during World War I.

Explorer Turned Politician

After the war, Bingham flew into politics. A Republican favorite, he became lieutenant governor of Connecticut in 1922 and was elected governor two years later. Before he was sworn in, however, US Senator Frank Brandegee committed suicide, and Bingham was urged to run for the vacant seat, which he won in a special election. As a result, Lieutenant Governor Bingham was sworn in as governor on January 7, 1925, went to his inaugural ball, and resigned to become senator, all in the same day. Bingham served as an aviation advocate in the US Senate until 1933, performing such press-worthy feats as landing a blimp on the Capitol steps and flying an autogiro (an aircraft with a propeller and a helicopter-style rotor) to play golf.

Remembering Hiram Bingham

Photograph by Hiram Bingham of the Sacred Plaza at Machu Picchu, Peru, ca. 1918 – Western History/Genealogy Department, Denver Public Library

Bingham always believed that the thing he would be remembered for was Machu Picchu. His 1948 runaway bestseller Lost City of the Incas helped make that a certainty. It became the basis for the 1954 Charlton Heston movie Secret of the Incas, which in turn served as a model for the mid-1980s films about the fictional archaeologist Indiana Jones.

Today, over 100 years after Machu Picchu’s rediscovery, tourists drive to the UNESCO World Heritage site along the Hiram Bingham Highway or take the luxurious Hiram Bingham train there. Both of these are signs that even Bingham’s critics recognize that he accomplished much for both archaeology and Peru. With the 2012 return to Peru of the artifacts Bingham brought to Connecticut completed, perhaps the stage will be set for an even greater appreciation of the memorable accomplishments of this Connectican abroad.

Walter Woodward is the Connecticut state historian emeritus.

© Connecticut Explored. All rights reserved. This article originally appeared in Connecticut Explored (formerly Hog River Journal) Vol. 10/ No. 1, WINTER 2011/2012.

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.