by Amanda Gurren

Conventionally, students attend school in the district where they live, but the option to choose other educational alternatives has been a part of Connecticut’s state policy for years. One of these educational alternatives included Project Concern, a program executed in 1966 that granted Connecticut students residing within city limits the ability to attend suburban schools. One of the earliest voluntary busing programs in the US, Project Concern was supplanted in 1998-99 by the Project Choice program (also known as Open Choice). Project Choice enabled the two-way movement of urban and suburban students in the areas neighboring Connecticut’s three largest cities: Hartford, Bridgeport, and New Haven.

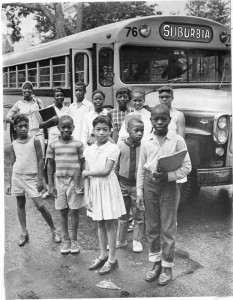

Early Student Participants of Project Concern Project, 1968 – Hartford Public Library, Hartford History Center, Hartford Times Collection

The Concerns that Prompted “Concern”

Due to the growth of white suburbs in the 1960s, and housing barriers that restricted minorities to Hartford, racial imbalance and concentrated poverty became pressing issues for the city school district. Parents, students, and school faculty members were among those who called for government intervention. Unsure of what measures might address and resolve the issues at hand most effectively, the city requested the aid of Harvard University to examine and assess Hartford and its respective public schools. The findings of Harvard University’s study of Hartford were later published in what is known today as the “Harvard Report.” The Report presented Hartford with a number of suggestions that the city could undertake to improve conditions in its schools. Although many of these propositions were never implemented due to the lack of sufficient funds, the idea of a state-funded metropolitan busing plan looked hopeful and, most importantly, affordable.

En Route to Change: The Beginning Years

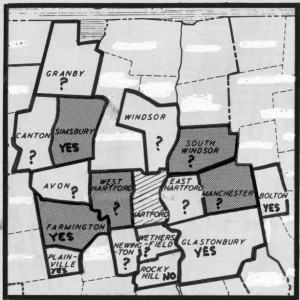

Project Concern, one of many US social experiments in desegregation at the time, was created by state and city education leaders with business support during the sweeping idealism of the 1960s. Hartford responded to Harvard University’s findings by experimenting with busing a randomly selected group of its inner city children to schools of five surrounding suburbs. During the project’s early years, more suburbs strongly opposed this desegregation program than volunteered to participate in it. Still, the project leaders hoped that the anticipated success of the experiment would encourage more suburbs to join the effort. During this two-year experimental phase, extensive records were kept of the academic and social progress of the 260 participating students. Reviewers compared this data to that collected from control groups of children who remained in the Hartford public school system. The encouraging results of the pilot effort convinced 10 other towns and white middle-class areas of Hartford to partake in the project and admit children from the target areas into their schools.

Results Meet with Mixed Reviews

Map of Hartford and its Surrounding Suburbs that Agreed to Participate in Project Concern, ca. 1966 – Hartford Public Library, Hartford History Center, Hartford Times Collection

Over time, Project Concern met with successes as well as failures—a mixed outcome that reflects the paradoxical nature of school desegregation efforts around the nation. In 1982, approximately 700 former program participants, including those who had graduated from secondary school and those who had not, were interviewed and surveyed for an evaluation report. Leading sociologist Robert Crain determined that attending the suburban schools significantly reduced high school dropout rates, increased adult socializations between whites and nonwhites, and increased the number of blacks who chose to live in interracial housing. Additionally, the report concluded that program participants had fewer complications with police, observed less discrimination in college and at their respective jobs, and were more likely to excel in college.

In spite of the documented gains, Project Concern also received its fair share of criticism. Some argued that the one-way busing program did not produce true or lasting integration. In fact, the burden of busing was placed solely on minority students (in contrast to desegregation programs involving two-way busing). Furthermore, critics of the program claimed that the number of program participants was a relatively small percentage of the total number of Hartford students. Even during the program’s highest enrollment years, Project Concern students never made up more than 8% of any participating district’s student population. The limited number of student participants consequently made it difficult to determine the statistical validity of evaluation findings. Yet, despite the obstacles, many of the Project Concern alumni recall it as a valuable experience that profoundly shaped their future opportunities.

Amanda Gurren, a double major in Urban Studies and Political Science and a sophomore at Trinity College in Hartford during the 2012-13 academic year, is a resident of Weston, Connecticut.