By Steve Thornton

James B. Covey was only 14 years old when Yale Professor Josiah Gibbs found him working on the New York docks. Gibbs was one of the Connecticut abolitionists determined to free the 53 Africans, known as the Amistad prisoners, who were on trial for their lives. The captives did not speak English and no one in Connecticut spoke Mende, the captives’ native language. Rev. Gibbs desperately needed an interpreter and this young man, who had been enslaved as a child, fit the bill.

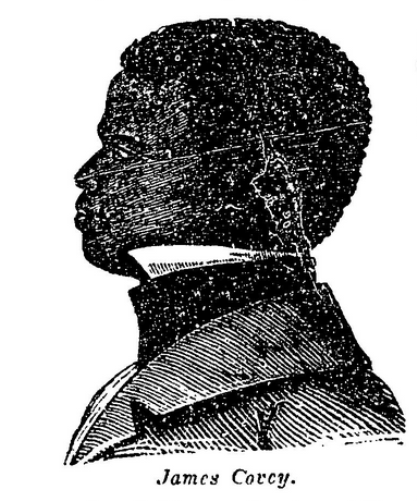

An illustration of James Covey from John Warner Barber’s book A History of the Amistad Captives:…”

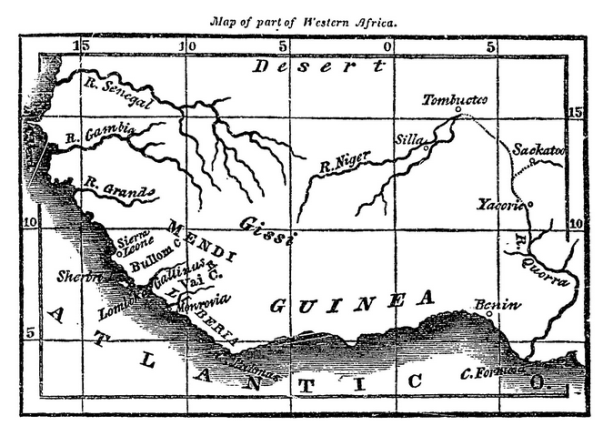

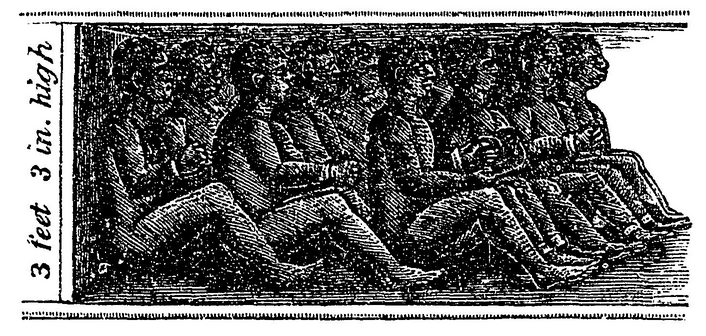

On July 2, 1839, the Africans seized the schooner Amistad from Portuguese slavers who planned to sell these free men as slaves in Cuba. In the fight to liberate themselves, the Africans killed two white crew members. Americans captured the ship on Long Island and took it to New London, Connecticut. Authorities then wrongly classified the men as runaway slaves, property, and murderers and imprisoned them in New Haven. The Mende captives ultimately underwent three separate trials, including a final appeal at the US Supreme Court, before finally being vindicated.

Because James Covey’s first language was Mende, also spoken by most of the enslaved men, he played a critical role in earning their eventual freedom. At the time, Reverend Gibbs admitted: “My knowledge of the Mende language I have acquired from James Covey in first instance, in the same manner as I derived my knowledge of the English language from my parents. I have evidence that it is the English language from my intercourse with others. I made out a vocabulary of the Mende language from James Covey, and I am now able by means of it to converse with twenty or thirty of the Africans.”

The Amistad Trials

The first trial took place in Hartford in September 19, 1839, but Covey was too ill to attend. Had the court been able to hear directly from the captives, the outcome might have been different. But instead the prisoners’ ordeal moved to the District Court in New Haven, where the young interpreter’s skills proved invaluable in allowing the captives to tell their own stories to defense attorneys and the court.

Covey’s work also uncovered a motive for the Africans’ mutiny that neither the court nor the public would have otherwise known. The Amistad‘s cook taunted the captives, leading them to believe that the crew intended to kill and eat them. The Mende had no way of knowing it was simply a cruel joke. The captives, their lawyers realized, acted in self-defense.

Shortly after the New Haven trial began, lawyers helped transform the rough young working man into a “presentable” witness (as shown in a lithograph portrait where he dressed in a formal suit). James Covey, dismissed as a “half civilized, totally ignorant African” by slavery apologists, spoke words that resonated louder than the slander, however.

An illustration depicting the position of Cinque and his companions on board the slaver during their passage from Africa, from John Warner Barber’s book A History of the Amistad Captives:…”

Despite his youth, Covey provided an authentic voice for the captives. In the process, he established his own identity beyond that of an orphan and former slave. His Mende name was Kaweli. He went by Covie in Sierra Leone after being liberated by a British naval ship. He later named himself James Benjamin Covey. History does not tell us why he chose Benjamin. Perhaps the name derived from the “B” burned into his flesh that labeled him as property before he was nine years old. Regardless, when the exonerated Africans finally sailed back to Sierra Leone in 1841, James Benjamin Covey made the decision to go with them, as a free man.

Steve Thornton is a retired union organizer who writes for the Shoeleather History Project