Early New England settlers found the Windsor area’s sandy loam the perfect soil for growing tobacco. Beginning in 1640, Connecticut farmers imported tobacco seeds from Virginia and by the mid-19th century the “Tobacco Valley,” which ran from Springfield, Massachusetts, to Hartford, Connecticut, had become a center for cash-crop production.

Commercial tobacco production expanded dramatically in the early 1800s thanks to the growing popularity of cigars among men in the US. Farmers in Windsor and the surrounding area specialized in growing tobacco for the two outer layers of the cigar—the binder and the wrapper. Though originally intended for local consumption, Connecticut tobacco soon found customers in cities like New York and Philadelphia.

By 1910, tobacco was the leading agricultural commodity in the valley: more than just shaping the landscape, the crop helped shape the region’s identity. This was especially true when it came to shade-grown tobacco.

Tobacco barns in Windsor, Connecticut – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Carol M. Highsmith Archive

Shade Tobacco Becomes Valley Trademark

Valley farmers traditionally grew three varieties of tobacco. The first two, Broadleaf and Havana Seed, made the best binders. These varieties prospered when grown outside, with full exposure to the sun. In the late 1800s, however, a fine-grained tobacco from Sumatra began replacing cigar wrappers made in the valley. To combat this, local farmers raised shade tents of hand-woven cloth over their crops to cut down on sun exposure and to raise the humidity levels surrounding the crop. This technique produced a thin, flavorful wrapper leaf that matched the quality of the Sumatran leaves. This new “shade tobacco” became the third and most famous variety of valley-grown tobacco.

Windsor first experimented with shade-grown tobacco in 1900. Farmers grew a half-acre of tobacco under these conditions on a plot of land on River Street in the village of Poquonock. The tent provided optimal growing conditions for the tobacco and the successful experiment initiated the shade tobacco era in Windsor. Thanks, in part, to this success, Windsor became the largest tobacco producer in Connecticut.

In order to support their operations, commercial growers became increasingly reliant on migratory labor. Tobacco was a very labor-intensive crop to produce and Windsor and the surrounding areas soon exhausted the supply of local help. With the onset of the immigration restrictions that accompanied World War I, local farmers resorted to drawing their seasonal labor from college campuses throughout the South.

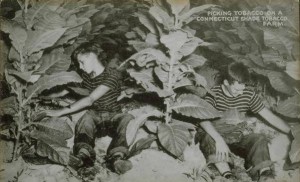

In addition to utilizing college students for summer work, farmers also took advantage of inexpensive child labor from local areas. Farmers brought children in on trucks in the morning and then returned them to their homes at night, avoiding costly housing expenses. Local children became indispensable in the completion of two important tasks: picking leaves and preparing them for curing in the sheds.

Two boys picking tobacco on a Connecticut shade tobacco farm – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Online

The World War II years brought further labor shortages, as did the passing of Connecticut’s 1947 Child Labor Bill, which set age and hourly restrictions on agricultural labor. Tobacco farmers looked to the West Indies for help. Beginning in 1947, Puerto Rican and Jamaican laborers came to Connecticut by the thousands to work in the tobacco fields. Hired as seasonal workers, many of them eventually settled in Connecticut, making a significant impact on the demography of the area that is still reflected today.

Like other forms of tobacco use, cigar smoking has seen significant decline in recent years, due in part to the health concerns associated with tobacco consumption. In addition, the development of cheap, mass-produced cigar wrappers by commercial enterprises has taken a significant toll on the local tobacco industry. In the 1930s, Connecticut had 30,000 acres of farmland dedicated to tobacco production; by 2006 this acreage had dwindled to less than 2,000 acres. Much of the former tobacco farmland is now used to grow nursery stock or has been developed into residential communities and shopping centers.

Museum Preserves Agricultural Heritage

In 1988, aware of the disappearing tobacco culture in the valley, local residents established the Connecticut Valley Tobacco Historical Society. Its mission was to preserve the stories and artifacts that made up such a significant part of the area’s identity. Thanks partly to a trust fund set up by John E. Luddy (a man who made a living selling shade cloth and other supplies to tobacco farmers), the Connecticut Valley Tobacco Historical Society was able to make a grant to the Town of Windsor for the construction of a tobacco museum at Northwest Park. Today, through its archives, collections, and exhibits, the Luddy/Taylor Tobacco Museum educates visitors on one of the most important aspects of Connecticut’s agricultural history.