Written by Damien Cregeau and Dayne Rugh for the Connecticut History Review

Though most of the famed battles of the American Revolution took place on land, in truth, the war would not have been won without several critical naval victories. On November 20, 1776, the Continental Congress passed a significant resolution authorizing a massive naval construction initiative aimed to strengthen the American presence at sea. This resolution came on the heels of Benedict Arnold’s tactical victory at the Battle of Valcour Island. Arnold’s entire fleet (built from the ground up) was decimated, yet his remarkable defense of Lake Champlain proved that victory against the British could be had on the water.

Building the USS Confederacy

The following year on January 23, 1777, two vessels were authorized to be constructed in Connecticut, one of which became the 36-gun frigate bearing the name Confederacy, a fitting nod to America’s first official form of government, the Articles of Confederation. The project fell to Joshua Huntington of Norwich who supervised the construction of the vessel. To build the ship, land was leased from Norwich local Ebenezer Story and work commenced on February 18. The shipyard would have existed along the shores of the Thames River, approximately five miles from Norwich’s Chelsea Harbor near the present-day Mohegan-Pequot Bridge in Preston.

The construction of the 153-foot vessel was an ambitious achievement for the local shipwrights and the vessel showed many distinctive design features including beautiful wood carvings and a vintage-style figurehead. In addition, the ship featured a particularly unique second propulsion system. Designers included as many as 28 oar ports beneath the ship’s gun ports which supplemented the ship’s sailing power and maneuverability and provided a means of propulsion if the ship was ever to be dismasted while sailing.

British Drawing of the USS Confederacy (1781) – National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. Used through Fair Use and Public Domain.

Records show that the construction of the Confederacy was met with delays and faced a constant absence of funds. After almost two years, the Confederacy finally launched on November 8, 1778, and received a tow to New London for the final phases of rigging and fitting out. An ad posted in the Providence Gazette, described the Confederacy as “a very fine vessel and perhaps superior to any ever built in America.” Indeed the ship was visually impressive as the Confederacy and another 36-gun frigate (named the Alliance) were among the largest ships constructed during the war. Further revealing, a sizeable number of Mohegan Native Americans and African Americans were among the ranks of builders according to the surviving Confederacy papers contained in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. A crew commanded by Seth Harding of Norwich was hired and included Ebenezer Story, who served as the ship’s carpenter for the duration of its service.

The Confederacy Enters the American Revolution

The Confederacy set sail on its inaugural cruise on May 1, 1779, taking the first of what became several British prizes. The ship sailed as a part of a larger squadron stationed in the North Atlantic under Commodore Samuel Tucker and in September of that year, the Confederacy was tasked with the pivotal assignment of delivering an important diplomatic delegation to France. The delegation consisted of French Minister, Count Conrad Girard, American Minister to Spain, John Jay, and their spouses.

Just a couple of weeks into their voyage from America to France, the Confederacy encountered a massive hurricane which dismasted the ship and caused severe damage throughout the vessel. The situation proved desperate for the crew yet the ship would be saved by its second propulsion system. Disagreement ensued over whether the Confederacy should push forward to France or make haste for the nearest friendly port; in the end, the decision was made to power the ship to the French colony of Martinique for repairs. The incident prompted significant delay in the Confederacy’s mission and the delegation found itself transferred to the French frigate L’Aurore, which arrived in Cadiz, Spain, on January 22, 1780.

While in Martinique, repairs were only partially completed on the badly maimed frigate as Congress scrambled to procure funds. To remedy the situation, the Continental navy, as well as privateers, ramped up efforts to seize British vessels and sell any captured loot. One British ship, the Sarah, was captured by the Continental sloop Saratoga in early 1780 and provided much needed cash flow.

Later that May, John Brown, Secretary of the Board of Admiralty for the Continental Congress, wrote to Captain Harding, instructing him to return to Philadelphia so that the Confederacy’s remaining repairs could be completed. Brown also ordered the immediate sale of large caches of wine seized by American privateers. During his time in Martinique, Captain Harding found himself in the middle of a large-scale investigation launched by Joseph Reed, President of the Pennsylvania Supreme Executive Council, for the impressment of British marines; ultimately, Captain Harding avoided prosecution.

A Revolutionary Ship Meets Its End

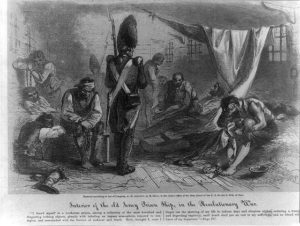

Interior of the old Jersey prison ship, in the Revolutionary War, where many of the Confederacy’s crew ended their service. – Engraved by Edward Bookhout, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. Used through Public Domain.

The Confederacy spent the remainder of 1780 and the winter of 1781 berthed in Philadelphia and encountered further delays in its refitting. By the spring, the Confederacy set sail for its second major cruise of the West Indies together with the Continental ships Deane, Saratoga, American privateer Fair American, and the French naval brig Cat. This cruise yielded the capture of the British vessel Diamond, laden with plunder taken from the British conquest of St. Eustatius. However, while patrolling off the Eastern Seaboard on April 14, 1781, the Confederacy was forced to strike its flag to two British ships of the line, theOrpheus and Roebuck. British newspapers celebrated the capture as the Confederacy’s crew languished as POWs aboard the British prison ship, the Jersey, and in the sugarhouse prisons of Manhattan. (Captain Harding later negotiated his release and relocated to New York where he passed away in 1814.)

With their new prize, the British towed the Confederacy to England and renamed it Confederate. Official drawings and specifications drafted there currently reside in the National Maritime Museum of Greenwich in London.

Upon reaching England, however, the British carpenters became dismayed at discovering the ship was wholly compromised due to heavy damage as well as the large amount of green lumber used extensively throughout its hull. They deemed the ship unusable and broke it up in 1782. The Confederacy faced an arguably untimely end, and never did attain the legendary acclaim as the USS Constitution, yet the mighty but imperfect Connecticut-built frigate nevertheless earned its status as a part of America’s first navy.

This is an abstract of a more comprehensive article published by the University of Illinois Press in the Fall 2019 issue of the Connecticut History Review.