By Kathleen Motes Bennewitz

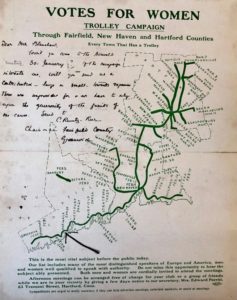

“The Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association (CWSA) continues to stir the State with its unique trolley campaign,” penned The Woman’s Journal, a venerable weekly published in Boston, on March 2, 1912. The suffrage drive being extolled was the “Votes for Women Trolley Campaign,” the tactical innovation of CWSA state organizer Emily Pierson. For three months—from January 24 to March 21—the campaign held rallies at every municipality with trolley stops—46 in all—in Fairfield, New Haven, and Hartford counties.

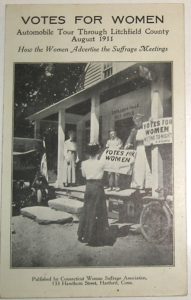

“Votes for Women Automobile Tour Through Litchfield County,” August 1911 – Courtesy of Dr. Kenneth Florey

The trolley campaign built on the success of the CWSA’s August 1911 “Votes for Women Automobile Tour through Litchfield County.” On that benchmark campaign, “the quiet tree-lined streets” of 27 towns were “invaded by automobiles” carrying parties of recent college graduates and state suffrage leaders. The women, along with guest speakers, galvanized audiences at meetings, adding new members and equal franchise leagues along the way.

For the lengthier winter trolley campaign, Pierson strategically leveraged a more expansive transportation network operated by the Connecticut Company, which at its peak in the 1910s ran over 2,200 cars on nearly 800 miles of track. Her route, planned along lines running from the New York border at Greenwich to the Massachusetts line near Suffield, made for an affordable, convenient way to travel to the events. Also central to the plan was that Fairfield, New Haven, and Hartford counties collectively contained 78 of the state’s 168 municipalities and 75 percent of the general population, which had grown exponentially with surges in immigration. By attracting large, broad audiences from the local and neighboring communities to its rallies, the CWSA sought to expand its support base, fund-raise, and win over voting men as well as influential citizens and legislators to help support woman’s franchise in upcoming sessions of the General Assembly.

Another newsworthy element was the speaker roster of over 80 prominent public figures and reformers from Connecticut, across the nation, and England. The remarkable list included US senators, a state governor, college presidents and professors, labor union leaders, and such notables as Inez Mullholland, Anna Howard Shaw, Jane Addams, Rheta Childe Dorr, and English suffragists Ethel M. Arnold, Margaret G. Bondfield, and Beatrice Forbes Robertson Hale; among the men were Charles Beard, Stanton Coit, Max Eastman, John H. Light, Owen Lovejoy, Ernest Thompson Seton, Lincoln Steffens, and Charles Zeublin.

Connecticut Suffragists Take to the Rails

“Votes for Women Trolley Campaign” program; inscribed by Caroline Ruutz-Rees, CWSA Fairfield County chairman, to Mrs. Agnes E. Blanchard, librarian, South Norwalk Public Library. Elise M. Hill Scrapbook (1912) – Clara Mossman Hill and Elsie M. Hill Collection, Fairfield Museum and History Center Library.

The CWSA launched the trolley campaign on January 24 at Bridgeport’s Warner Hall, with speaker Max Eastman—the secretary of the New York City’s Men’s League for Woman Suffrage and the soon-to-be editor of the socialist periodical, The Masses. It culminated with great fanfare on March 28th at Parson’s Theatre in Hartford. In between, Pierson’s “trolley leaguers” crisscrossed each county at a dizzying pace, presenting four to six evening rallies per week.

Throngs of fervent suffragists, together with the curious, undecided, and even antis, filled the venues—town halls, theaters, libraries, and beach casinos—to hear the reformers and calls to mobilize from Katharine Houghton Hepburn, Josephine Day Bennett, Annie Gertrude Porritt, and other CWSA leaders. Emily Pierson was on the dais at practically every stop to share the objectives for waging this campaign, especially in small towns. Since each municipality, regardless of size, was represented by two representatives in Hartford, making full suffrage a local issue, she explained, could influence the nomination and election of pro-suffrage legislators.

Decorated automobiles of CWSA suffragists swarmed Litchfield County in August 1911 – CWSA Records (RG 101), Connecticut State Library.

The 1912 trolley crusade proved tremendously successful with over 23,400 people addressed and 2,320 new supporters signing a petition declaring, “I believe in equal suffrage for men and women.” For many towns, the campaign was a maiden suffrage event or launched an equal franchise league, and by the November 1912 annual meeting, the CWSA had increased its auxiliaries from 18 to 47, with many emerging along this campaign route.

In the wake of the trolley campaign, the suffrage movement rapidly gained ground across the state. To push the momentum, the CWSA next invaded New London County with a summer automobile tour, then planned campaigns for the remaining three counties. As The Woman’s Journal aptly stated that July, “For the Connecticut suffragists, every year is a campaign year, and both the State Association and the local leagues, which are affiliated with it, are determined that there shall be no slackening of activities until an amendment of the State constitution has granted Votes for Women.”

Kathleen Motes Bennewitz serves as Westport’s town curator and helps manage the Westport Public Art Collections. She has worked for art and historical museums across the country and today is an independent American art historian and exhibition curator.