By Amanda C. Burdan, PhD

Driven throughout his career by a devotion to craftsmanship, technical mastery, and realism, Lyme printmaker Thomas W. Nason built a lasting reputation for his poetic, somber observations of rural New England. Although his work appeared to stand apart from current art world trends, Nason quietly absorbed and processed influences from a broad range of sources, including Modernism, while working from his studio on Joshuatown Road.

A Self-taught Perfectionist

Born in 1889 and raised on a farm in Billerica, Massachusetts, Thomas Nason served in the Army during World War I and pursued various jobs in civil service and business. In 1921, Nason’s intellectual curiosity turned him toward art, which would become his lifelong career. He taught himself the discipline of printmaking through books, observation, and the laborious process of trial and error. He collected prints and voraciously read practical manuals as well as histories of printmaking and art, including the modern movements of Europe.

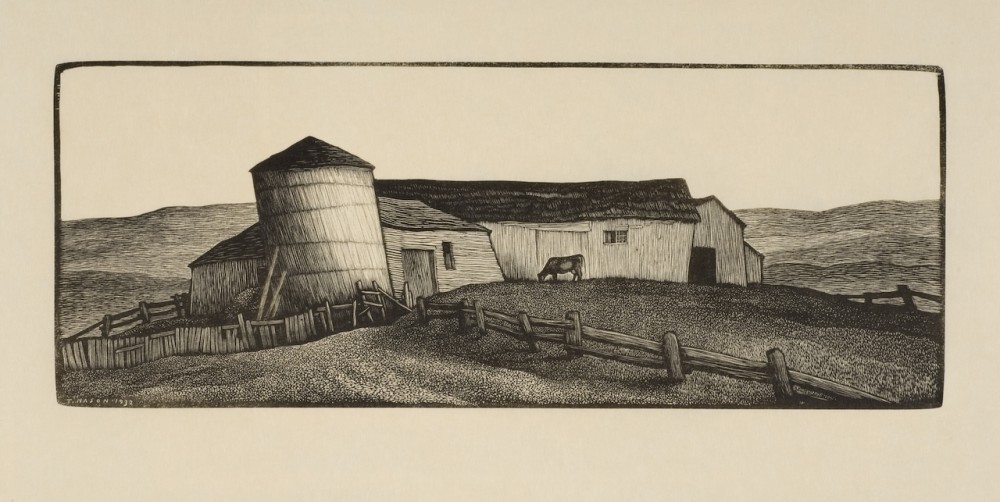

Thomas Nason, Farm Buildings, 1930, wood engraving – Florence Griswold Museum

Nason soon gravitated to wood engraving as his favored means of printmaking. Wood engraving is a form of relief printing in which the artist cuts wood away from the block, often with very fine incisions. The remaining, raised areas of wood are rolled with a thin layer of ink for printing. In the 1800s, wood engraving became the preferred means of reproducing images for publications such as Harper’s Weekly. With the onset of photographic processes, however, the demand for wood engravings subsided until an artistic revival in the 1920s, which served as inspiration for Nason.

Lyme Becomes Nason’s Muse

In Lyme, Connecticut, and the surrounding countryside, Nason found his ideal subject matter and mood: colonial homes, vernacular architecture, and other symbols of austere rural life. Though his many of his New England contemporaries portrayed nearly identical subjects, Nason took great pride in cultivating an independent style.

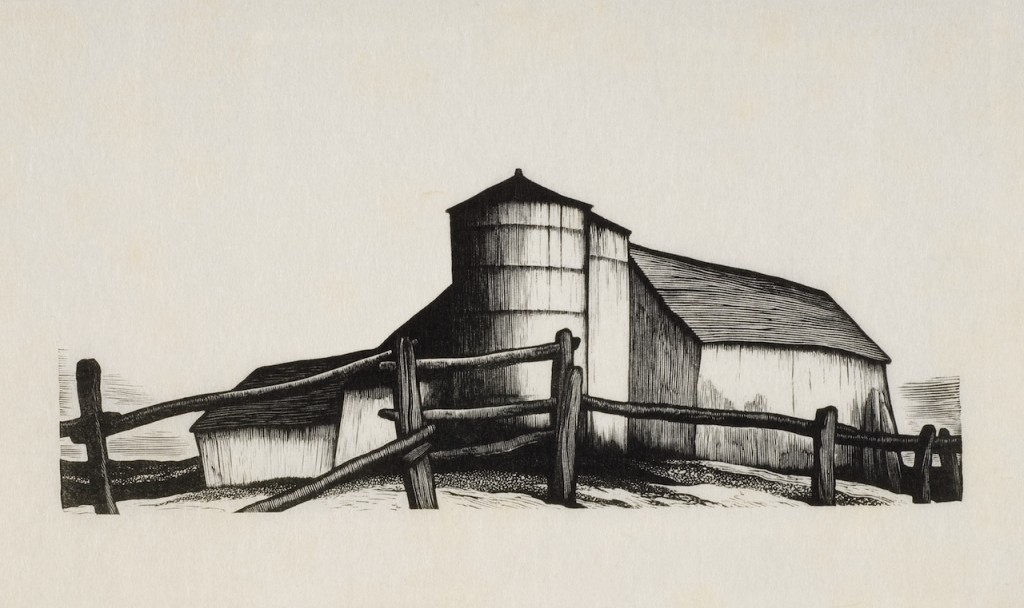

Thomas Nason, A Deserted Farm, 1931, wood engraving – Florence Griswold Museum

With a pure, observational simplicity, Nason delivered a quiet eloquence in works such as Farm Buildings(1930), with its stately silos. Here, lines are rendered precisely, forms are massed sparingly in a kind of silhouette, and shadows, when they exist, are bold and exact. While this farm gives the appearance of solidity and strength, Nason would increasingly turn his attention to more decrepit architecture, nestled into rolling country hills.

Nason and his wife Margaret fell in love with an abandoned Lyme homestead on top of Shippee Hill along Joshuatown Road. They purchased the ruins of the colonial home in 1931 and slowly rebuilt the house as their Depression-era finances allowed. “We were among the early invaders from the city,” Nason wrote in 1965. Like other artist working in the area, Nason began to dwell nostalgically on New England rural life, which was beginning to pass away even as he recorded it.

Illustrating the Poems of Robert Frost

Like the 19th-century wood engravers before him, Nason accepted commissions for a variety of commercial projects. He frequently worked for The Spiral Press, one of the most respected artistic publishers of the 20th century, run by Joseph Blumenthal. The New York City-based press published for Robert Frost, W.H. Auden, William Carlos Williams, and Franklin Roosevelt, among others, and created special volumes for such institutions as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Pierpont Morgan Library. Blumenthal recommended Nason to Frost when the poet and his publishers were looking for a new illustrator for Frost’s poetry.

Never were Nason’s engravings more closely aligned with poetry than when he illustrated the verse of Robert Frost. Frost’s status as the quintessential rural New Englander, writing in simple, direct, and yet forceful terms about American life makes a ready comparison to Nason’s life and work. Frost’s poems, like Nason’s prints, pay tribute to rural life in familiar terms. While Nason was known as the “poet engraver of New England,” Frost was revered as “the poet farmer of New England.”

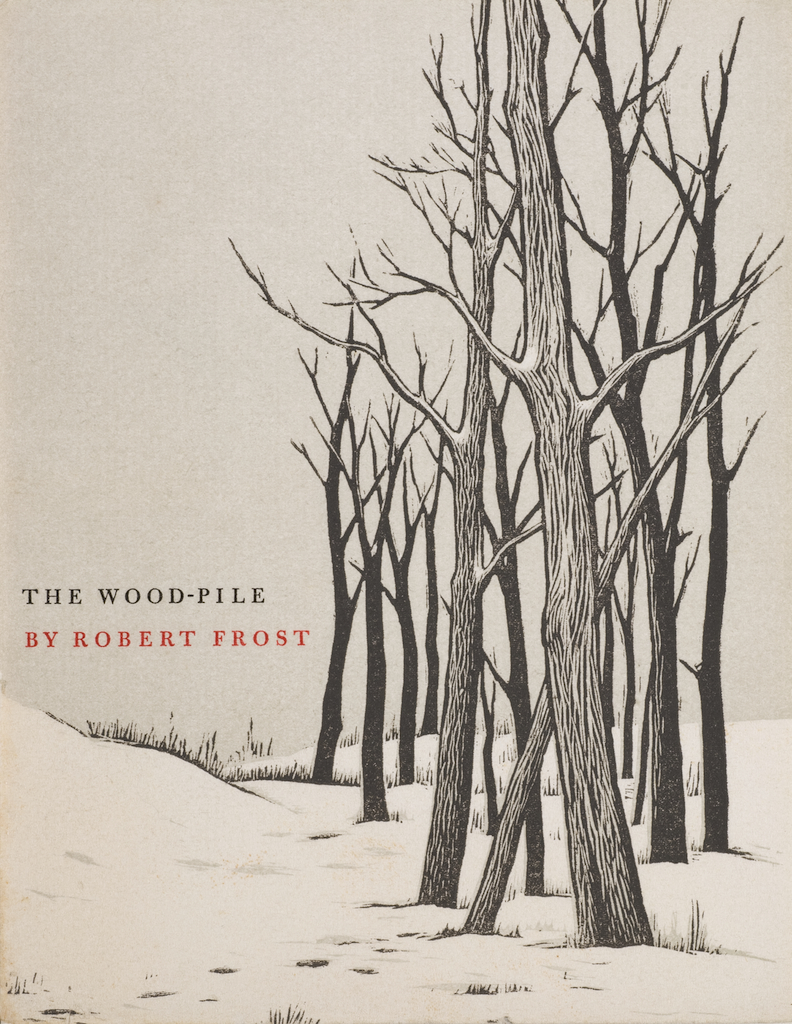

Thomas Nason, Trees in Snow, 1961 On the cover of Robert Frost’s The Wood-pile, printed by The Spiral Press – Lyme Historical Society Archives, Florence Griswold Museum

The carefully carved, deliberate lines in Nason’s wood engravings are akin to Frost’s carefully chosen, measured language. Frost selected Nason to illustrate several of his best-known poems, including “The Road Not Taken.” The works of Nason and Frost parallel each other in their straightforwardness of presentation but also in their traces of underlying despair.

By the end of their lives Frost’s and Nason’s reputations were forever intertwined. Nason’s iconic image of an abandoned fence post appeared at the opening of several volumes of Frost poetry as well as being prominently featured in the memorial booklets published on the occasion of each man’s death. Nason’s illustrations proved equally appropriate for other American poets as well. Publishers commissioned him for comprehensive volumes on William Cullen Bryant and Henry David Thoreau.

Realism Meets Regionalism and Modernism

In the face of increasingly abstract works of art produced in Europe early in the 20th century, American taste ran resolutely toward realism. The leading realists of Nason’s time were the American Regionalists, many of whom were printmakers as well as painters. Although devoted to depicting American life—and particularly fond of rural scenes—the most well-known Regionalists, such as John Steuart Curry, Thomas Hart Benton, and Grant Wood, represented the culture and history of the Midwest. Nason and a small group of New England Regionalists exactly parallel the Depression-era agrarian themes favored by their Midwestern counterparts.

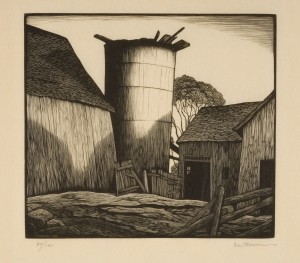

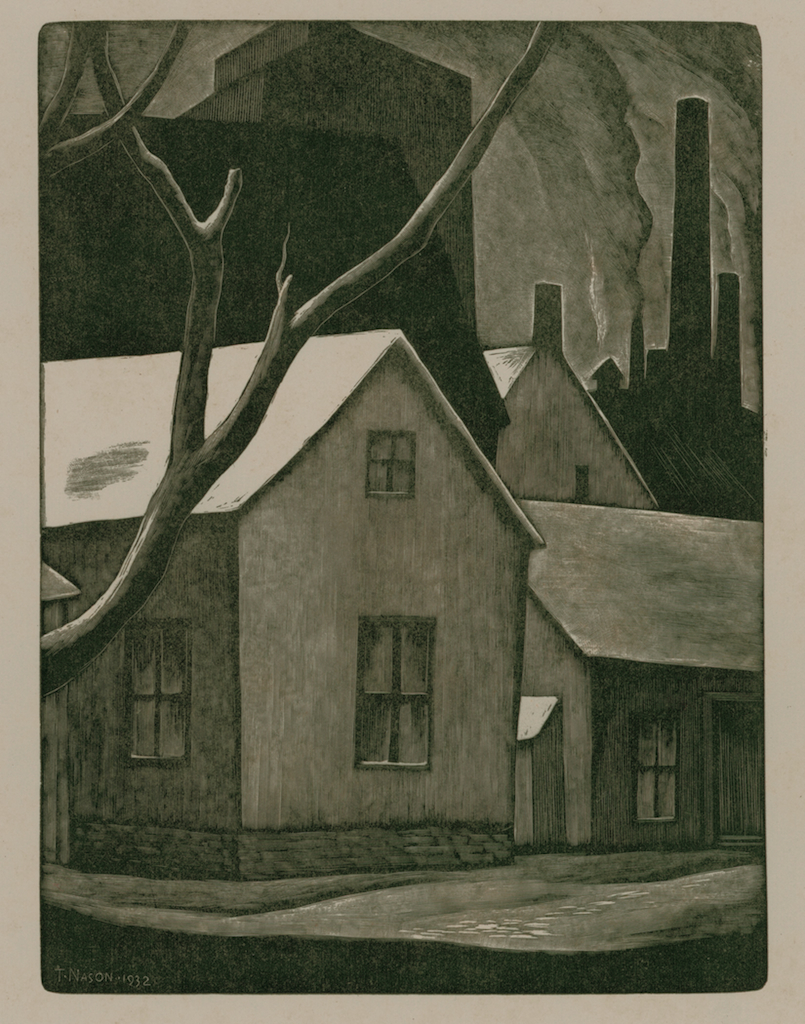

Thomas Nason, Factory Village, 1931, wood engraving – Florence Griswold Museum

Rarely considered modern in their subject matter, Regionalists did, however, drift from strict realism toward the stylized forms and figures favored by Modernists. For example, the exaggerated slope of a barn roof or the extreme undulations of the soil in some Regionalist works shared an expressive quality often found in Modernist works. This mix of realism, Regionalism, and Modernism can be seen in the oblique slant that Nason gave to the architecture in The Leaning Silo (1932). The details go beyond pure visual description; they amplify the mood of the scene. The awkward tilt of the structure heightens the scene’s desolation and creates the sense that the building, like the farmland it looms over, has been pushed to its breaking point.

The influence of Modernism can also be seen in Nason’s selection of an industrial subject in Factory Village (1932). Fellow artist and print connoisseur John Taylor Arms praised the emotive qualities of the print in April 1937 issue of The Print Collector’s Quarterly. He wrote, “The cold, stark, dreary corner of a deserted street in an American mill town; the tumbled buildings, unbeautiful in everything except the pictorial interplay of their surfaces and their meaning as symbols of the life they house; the chimneys piled against the drab sky; this is the stuff out of which Nason has told his story.”

As a poetic chronicler of the old New England landscape yielding way to the 20th century, Nason had few equals. Through his successes, he continued to study and work at his farm in Lyme until his death at 82 in 1971.

Amanda C. Burdan, PhD, is Assistant Curator at the Brandywine River Museum in Pennsylvania and former Assistant Curator of the Florence Griswold Museum, where she curated The Road Less Traveled: Thomas Nason’s Rural New England.