By Edward T. Howe

The Litchfield Law School, founded in 1784 by Tapping Reeve, became the first professional law school in Connecticut, the first proprietary (i.e., ownership) law school not affiliated with an educational institution in the United States, and the second oldest law school in the nation (after the William & Mary Law School in Virginia). After Reeve left in 1820, his partner, James Gould, ran the school until 1833 when it closed.

The Arrival of Tapping Reeve

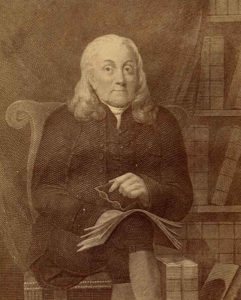

Tapping Reeve, founder of the Litchfield Law School, Litchfield, CT. – Litchfield Historical Society

The Town of Litchfield, located in the hilly northwestern part of the state, was incorporated by the General Assembly in 1719. A year later, settlers arrived mainly from Farmington, Hartford, Lebanon, Wethersfield, and Windsor to till the soil and to provide needed skills and crafts (e.g., brewer, wheelwright). Importantly, the town became the Litchfield County seat in 1751 with a sheriff and a court to decide criminal and civil cases. An important crossroads developed as people from neighboring towns traveled to the courthouse and conducted market activity in Litchfield.

Tapping Reeve arrived in Litchfield in 1772, with his wife Sally, to launch his law practice. In 1774, Aaron Burr, Reeve’s brother-in-law, became his first law student. As his reputation as an effective tutor spread, Reeve built a school building in 1784 capable of housing approximately ten to fifteen students per year. There were no entrance requirements, but many attendees had already obtained a college education.

Most legal training from the colonial period well into the nineteenth century involved the apprentice system or “reading law” with an experienced attorney. An apprentice generally studied about three years before taking the bar examination. In contrast, Reeve instituted a training program of formal lectures that lasted fourteen to eighteen months. The lectures focused on particular topics or “titles” (e.g. master and servant, husband and wife), embodying an assessment of general legal principles grounded in ethics. After each lecture, students had access to a law library to enhance their understanding of their notes. Since test grades and diplomas were not given, students attempted to impress Reeve (and after 1798, his only partner, James Gould) with performances on weekly informal tests and moot court sessions.

Litchfield Expands

After the end of the Revolutionary War in 1783, both the county and town of Litchfield prospered. The population grew as farmers, merchants, craftsmen, tavern keepers, and incipient manufacturers took advantage of expanding markets. New turnpikes, more stagecoach lines, an emerging postal system, an educated populace, and a newspaper fostered this economic expansion. Meanwhile, the long-entrenched Congregational Church and Federalist Party provided social cohesion and stability. Both of these conservative institutions stressed a ranking social order, the preservation of the status quo, and a respect for authority. Thus, this economic, religious, and political setting formed a fitting background for an increasingly favorable reputation for the law school and the founding of Sarah Pierce’s Litchfield Female Academy in 1792.

Both the law school and the academy drew students from all parts of the country, with about one-half of the combined total coming from New England. The proximity of the schools facilitated various social activities for making new friends and enhancing more personal relations. When marriages occurred, both husbands and wives benefited from their rising financial and professional status and attendant societal obligations. Moreover, an extended geographical network of personal, business, and political relationships augmented the influence of the school attendees in their various pursuits well into the nineteenth century.

Yet an embryonic yearning for a more democratic political system in Connecticut—advocated by small farmers, merchants, teachers, and religious dissenters—began after 1800 with the election of Thomas Jefferson of the Democratic-Republican Party. This movement posed a direct threat to the Federalist-Congregational Church alliance and the law school and female academy that aligned with them. This growing opposition achieved a major victory in 1817 when the newly formed Toleration Party captured the Connecticut governorship under Oliver Wolcott Jr. and a majority of the General Assembly. A new state constitution, ratified the following year, eliminated all taxpayer support for the Congregational Church and extended voting rights. The ensuing decline in the Federalist Party, combined with the debate over slavery, partly contributed to reduced enrollments at both Litchfield schools.

End of the Litchfield Law School

Ultimately, the loss of Reeve and Gould led to the demise of the law school. From a peak of fifty-five students in 1813, yearly enrollment dropped precipitously after the charismatic Reeve retired in 1820 (he subsequently died in 1823) and continued downward along with Gould’s failing health. Only six students remained when Gould closed the school in 1833. Arguably, the main external reason for its closing was emerging competition from incorporated university-affiliated law schools. These included William & Mary (1779), Transylvania University in Kentucky (1799), Harvard (1817), and Yale (1826).

In contrast, the Litchfield Law School never incorporated. Incorporation could have meant continuity; more funds for administration, law professors, staff and facilities; and an endowment. Nonetheless, the law school left an impressive legacy. Between 1774 and 1833, at least 945 students were enrolled. They subsequently entered a wide range of professions—particularly politics and the law. At the federal level, about 100 graduates were elected to the House of Representatives, 88 were appointed to the U.S. Senate by state legislatures, and six joined presidential cabinets. Two prominent attendees, Aaron Burr and John C. Calhoun, served as U.S. vice presidents; while three others (Henry Baldwin, Ward Hunt, and Levi Woodbury) received appointments to the U. S. Supreme Court. Many others were elected or appointed to a variety of legal positions at the state or local level. Their success, along with attendee achievements in other occupations, was a testament to the conceptual framework of the law school. Reeve and Gould believed that the formal study of law should be separate from undergraduate studies, that general principles of law should be applicable to the nation, and that this training would prove most useful in the development of any new laws needed for changing societal conditions.

Edward T. Howe, Ph.D. is Professor of Economics Emeritus at Siena College near Albany, New York.