By Peter Vermilyea

A national impulse to establish grammar schools for young children and academies for those considering college characterized educational efforts in the years following the American Revolution. While several academies existed for girls, few proved more influential than Sarah Pierce’s Litchfield Female Academy.

George Catlin, Sarah Pierce, portrait miniature, watercolor, ca. 1825 – Litchfield Historical Society

Pierce was born in Litchfield in 1767. She never married and instead dedicated her life to educating young women. Pierce’s father died when Sarah was 16, and her brother, John Pierce Jr., invested in an education for his sister to encourage her to become a teacher and support herself. Pierce taught her first classes in the dining room of her home.

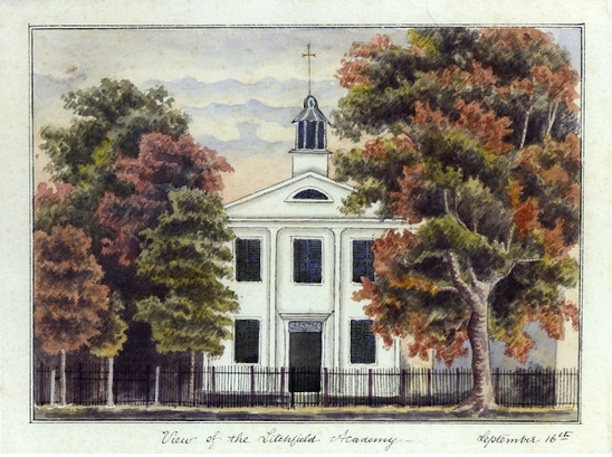

By 1798, the school Pierce began went by the name of the “Female Academy” and Pierce began a subscription list to fund the construction of a new school building, which by 1803, sat at a site on North Street indicated today by a stone marker. Here Pierce introduced young women to her revolutionary ideas about education—namely, that girls should be taught the same subjects as boys. These subjects included such intellectual staples as geography and history. Pierce even went so far as to write her own histories when she could not find suitable texts.

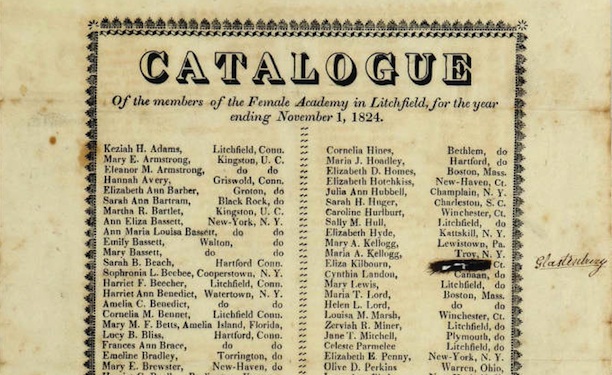

At the turn of the 19th century, students arrived in such large numbers—130 in one year alone—that Pierce needed to hire additional teachers. The subjects taught soon grew to include chemistry, astronomy, and botany. Instructors then balanced a student’s academic pursuits with artistic endeavors such as music, dancing, singing, embroidery, drawing, and painting. Additionally, students also received instruction in proper etiquette, as evidenced by the following rule:

You are expected to rise early, be dressed early, be dressed neatly, and to exercise before breakfast. You are to retire to rest when the family in which you reside request you. You must consider it a breach of politeness to be requested a second time to rise in the morning or retire of an evening.

Pierce brought in her nephew, John Pierce Brace, a graduate of Williams College, as a teacher and her ultimate successor as head of the school. Brace took hands-on approach to education, as noted by Mary Wilbor in 1822:

Mr. Brace had all his bugs to school this P.M. He has a great variety, two were from China, which were very handsome, all the rest were of Litchfield descent, and he can trace their pedigree as far back as when Noah entered the ark.

Early Student Housing

Pierce’s students boarded with Litchfield families. The town contained several large boarding houses (including Aunt Bull’s on Prospect Street) many of which took in students from the Female Academy and the Litchfield Law School.

Mary Ann Bacon attended Pierce’s academy in 1802, and boarded with the Andrew Adams family on North Street. Her diary entry for June 14, 1802, provides insight into a typical student experience:

Arose about half past five, took a walk with Miss Adams to Mr. Smith’s to speak for an embroidering frame. After breakfast went to school. I heard the Ladies read history, studied a Geography lesson and recited it. In the afternoon I drew read and spelt. After my return home my employment was writing and studying I spent the evening with Mrs. Adams and retired to rest about half past nine o’Clock.

Over 3,000 young women—and about 120 young men—received instruction at Pierce’s school before it closed in 1833. Their intellectual, social, and artistic abilities helped make Litchfield one of early 19th-century America’s most cosmopolitan towns.

Peter Vermilyea, who teaches history at Housatonic Valley Regional High School in Falls Village, Connecticut, and at Western Connecticut State University, maintains the Hidden in Plain Sight blog and is the author of Hidden History of Litchfield County (History Press, 2014).

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.