Nancy Finlay for Your Public Media

On January 1, 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect, declaring more than three million African Americans in those states in rebellion against the United States to be forever free. An article in the Hartford Daily Courant on January 2nd proudly declared that “Now, for the first time in history, the Government stands unequivocally committed to the support of the fundamental principles on which it was founded.” Reactions were mixed overall and ranged from raucous celebrations to expressions of deep concern about the impact of the sudden liberation of so many people.

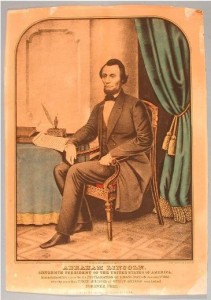

Abraham Lincoln. Hand-colored lithograph by E.B. & E.C. Kellogg, 1863. Celebrates Lincoln as the Great Emancipator – Connecticut Historical Society

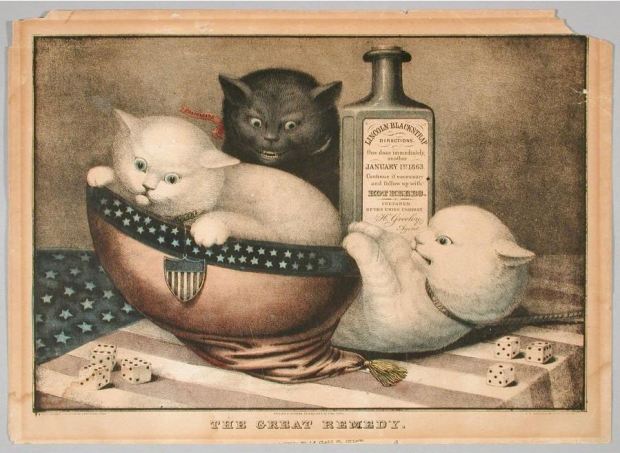

Hartford printers and print publishers reacted positively to the event and issued a numbered of memorable images celebrating the Proclamation. The Great Remedy is one of a series of lithographs issued by E.B. & E.C. Kellogg dealing with the questions of slavery and emancipation. Issued in advance, the print depicts the Emancipation Proclamation as the remedy to slavery, embodied in a bottle of blackstrap molasses, with directions “one dose to be taken on January 1, 1863. Continue if necessary.” A portrait of Abraham Lincoln shows the President seated, pen in hand, with the Proclamation on a table beside him. The caption declares that Lincoln “immortalized his name by the Proclamation of Emancipation, January 1st 1863.” One of the most dramatic renderings of the consequences of Emancipation, a large steel engraving published in Hartford by Lucius Stebbins a year later, shows a Union soldier reading the Proclamation to a group of African Americans in a slave cabin by torchlight. The delay in publication may have been due to the fact that engraving was a much more labor-intensive process than lithography, so that the big print undoubtedly took some time to produce. The Courant recommended the engraving as a “handsome addition to a home [picture] gallery.” The print was photographed and small carte-de-visite versions of it were offered for sale, for inclusion in photograph albums.

The Emancipation Proclamation was a great moment in world history as well as a turning point in the American Civil War. While the war would drag on for two more years and it would be another century before African-Americans achieved full equality under the law, the Emancipation Proclamation was, nevertheless, a monumental achievement. The response of Hartford’s printmakers suggests that they fully appreciated its importance.

Nancy Finlay, formerly Curator of Graphics at the Connecticut Historical Society, is the editor of Picturing Victorian America: Prints by the Kellogg Brothers of Hartford, Connecticut, 1830-1880.

© Connecticut Public Broadcasting Network and Connecticut Historical Society. All rights reserved. This article originally appeared on Your Public Media

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.