By Richard DeLuca

In the spring of 1925, aircraft engine designer and aviation engineer Frederick B. Rentschler came to Connecticut to pursue an idea that became one of the most successful ventures in American aviation industry. Like many such instances, Rentschler’s success resulted from a unique combination of technical know-how, social relationships, and happenstance.

The pivotal chance circumstance in Rentschler’s story was the 1922 passage of the Washington Naval Treaty, the result of a five-nation negotiation to disarm the major naval powers of the world. The treaty limited the construction of war ships by limiting ship tonnage. With two large battle cruisers already in production, the United States Navy decided to conform to the treaty by converting the two cruisers from gunships to aircraft carriers, thereby creating an immediate need for 200 fighter aircraft with which to stock the carriers.

Rentschler Promises US Navy a Better Aircraft Engine

Rentschler, a former Navy lieutenant convinced that “the best airplane could only be designed around the best engine,” as historian Mark P. Sullivan notes, suggested to the Navy that he could meet their standard for a 400-horsepower engine weighing 650 pounds or less—a feat that other manufacturers considered beyond their reach. With encouragement from the Navy, Rentschler assembled a design team and looked for investment capital and a place to set up shop.

A graduate of Princeton University, Rentschler came from an industrious Midwest family with social connections, and through his banker brother soon learned that the Pratt & Whitney Machine Tool Company of Hartford, with its long history as a manufacturer of precision tools, had both capital to invest and extra factory space. As it happened, the president of Pratt & Whitney’s parent company, Niles-Bement-Ponds, was a friend of the Rentschler family, and with little fuss a deal was struck in July 1925 creating the Pratt & Whitney Aircraft Company as a separate business with Rentschler at the helm. The following month, Rentschler and his design team, led by chief engineer George Mead, moved into the Capitol Avenue factory that a few years earlier had been home to the Pope-Hartford Electric Automobile Company and began to work on the Navy’s engine.

Wasp and Hornet Feature Innovative Air-cooled Radial Design

Rentschler’s vision centered on the design of an efficient, air-cooled radial engine. Unlike the V-8 automotive engine adapted for aviation use, or existing liquid-cooled radial engines, an air-cooled radial would provide more power with less weight. By Christmas, Rentschler and his team had produced an ingenious radial design that made use of a split crankshaft to increase the engine’s revolutions per minute without generating additional heat. The result was an engine that produced 425 horsepower while weighing only 650 pounds.

Searching for a name for the engine from among the family of fast-flying insects, Rentschler’s wife suggested the “Wasp.” Soon after, Rentschler’s team had produced a second air-cooled radial named the “Hornet” that was rated at 525 horsepower, and by October 1926 the US Navy had placed an order for 200 Wasp and Hornet engines, thereby insuring the short-term financial success of Pratt & Whitney Aircraft.

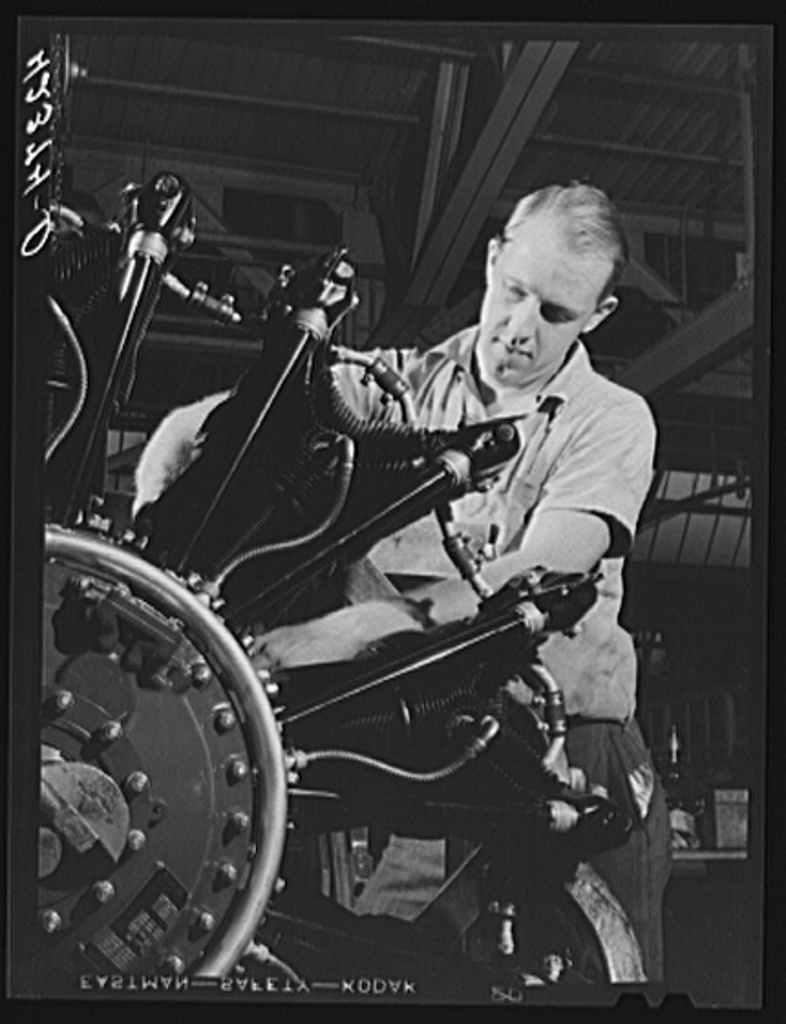

A worker on the final assembly of a WASP engine in the East Hartford plant, 1940 – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

WWII Brings Dramatic Growth

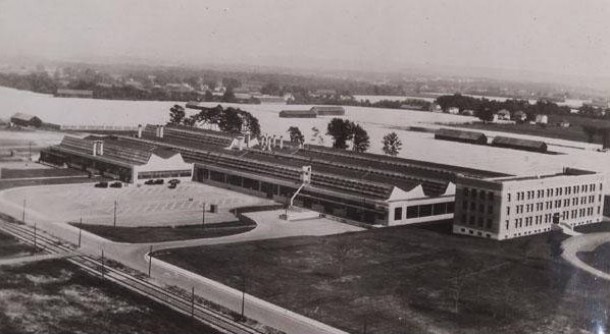

The dependability of the Wasp and the Hornet also made them popular among commercial aircraft manufacturers, and as the manufacturing of airplanes for commercial use increased, so did the demand for Pratt & Whitney engines. Meanwhile, continued demand for more powerful engines for military use added to the company’s prosperity. To keep up with production, the company moved its operations in 1929 to a large new plant it built in East Hartford on a 1,100-acre site, which included an adjacent airfield for flight testing its aircraft engines. The airport was soon named Rentschler Field.

By 1940, Pratt & Whitney’s engine technology had improved dramatically. The company’s largest engine, the Twin Wasp, produced 1,200 horsepower. As President Franklin Delano Roosevelt moved to put the country on a wartime footing, American aircraft manufacturers were called on to produce 50,000 aircraft a year for the military. To meet the challenge, Pratt & Whitney by 1943 expanded its workforce from 3,000 employees to 40,000. The company also recruited automakers, including Ford, Buick, and Chevrolet, as subcontractors, training the auto companies to duplicate the Pratt & Whitney manufacturing process.

Pratt & Whitney engineers continued to innovate, increasing the power of their engine designs throughout the war years. By the end of the war, the power of Pratt & Whitney’s largest engine had tripled to 3600 horsepower, and the company and its licensees had managed to produce more than 363,000 aircraft engines, an amount equal to one half the total air power of the Allied Air Forces.

In the post-war years, the company adapted to the modern air age with the manufacture of jet turbine engines beginning in the 1950s. Today, as part of the United Technologies Corporation, Pratt & Whitney continues to be an innovative manufacturer of jet turbines for commercial and military use worldwide, as well as one of Connecticut’s larger employers.

Richard DeLuca is the author of Post Roads & Iron Horses: Transportation in Connecticut From Colonial Times to the Age of Steam, published by Wesleyan University Press, 2011.