By Sally Sanders

As Connecticut’s only inland battle of the Revolutionary War, the Battle of Ridgefield is a major part of the history of Ridgefield and western Fairfield County. Taking place in April 1777, the Battle of Ridgefield was part of a larger British expedition to destroy Continental supplies in Danbury.

The Road to Ridgefield

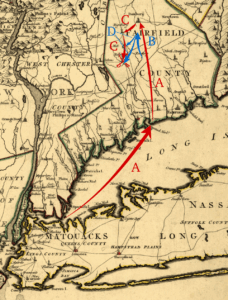

1780 map modified to depict British and American movements leading up to the 1777 Battle of Ridgefield. – Modifications by Bernard Romans on 1780 base map, Wikimedia Commons. Used through CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

On Friday, April 25, 1777, over 1,800 British troops suddenly arrived by ships off (present-day) Westport’s Compo Beach. By the time all the soldiers and their gear came ashore, it was late in the day and the weather was cold and rainy. The night-time march they began was hard, and every so often there were small attacks by the local militia. The British were headed for Danbury where they planned to destroy or carry off the supplies that General George Washington’s Continental forces had stored there.

Arriving on Saturday after their overnight march, the British found the military stores, took what they wanted, and burned many buildings in Danbury. General William Tryon directed the British contingent; he placed a Loyalist regiment (also called “Tories,” Americans who favored the king) led by Colonel Montfort Browne at the head of the line of march. General Tryon thought that this show of force would encourage loyalty to King George III of England rather than support for the Patriots. The British believed that there were many Loyalists in Connecticut and that they just needed some encouragement to stand with the king and welcome the British troops.

While General Tryon’s men were on their way to Danbury, word had gone out about the invasion and Patriot militias (locally organized groups of armed men) began racing to the area. They organized under the command of the Continental Army’s General David Wooster, Brigadier General Benedict Arnold, and Brigadier General Gold Selleck Silliman. In addition to local militias, the force included soldiers of the Continental Army who were nearby. Days earlier, the Continental Army had sent troops towards Peekskill, New York in response to a diversion tactic ordered by British General Howe.

The longer the British stayed in Danbury, the more they were in danger from Connecticut militias who were assembling. Very early on Sunday morning, April 27, the British left Danbury marching in a long line that included wagons loaded with supplies taken from the depot. They did not return to their ships the way they had come, however, but headed west through Danbury, then south into Ridgebury and on to Ridgefield.

The Battle of Ridgefield

General David Wooster Historical Marker, circa 2014. – By Brianegge, Wikimedia Commons. Used through CC0 1.0 deed.

At first, the Patriots did not know where the British were going—some thought they were headed west to the Hudson River and others thought south towards Ridgefield. Generals Arnold and Silliman took about four hundred troops and marched toward Ridgefield. Meanwhile General Wooster, with a smaller contingent, headed out to follow and attack the rear of the British line.

Historians describe three “engagements” as having taken place in Ridgefield, but recent research makes the case that Patriots were continually harassing the British troops as they marched up through Ridgebury. Shortly after the British had stopped near Lake Mamanasco for a brief rest and some food, General Wooster and his troops attacked the rear of the line. Considered the first engagement, they captured a number of British soldiers and took back some of the wagons and supplies that had been commandeered in Danbury.

Following the British as they neared the center of Ridgefield, General Wooster led another attack as part of the second engagement but was badly wounded. His men carried him off the battlefield and their attack ended; General Wooster died a few days later in Danbury.

Meanwhile, Generals Arnold and Silliman were organizing their troops and setting up a barricade at the northern end of town to prepare for the third engagement. Built of wood, wagons, and whatever the soldiers and volunteers could quickly put together, the barricade was where the Patriots wanted the British to stop and fight.

The British line, colorful and loud, was nearly a half-mile long and visible from the barricade on the ridge at the center of Ridgefield. Severely outnumbered, the Patriots stood their ground for a while, but when British soldiers began to circle around from the west and east, they were forced to withdraw. General Arnold’s horse was shot out from under him and injured Arnold’s leg as the animal fell. Accounts of the battle say that Arnold was able to pull out his pistol and shoot a British soldier who ran up to capture him.

Arnold escaped and the British, still taking fire, moved through the town. They set fire to various homes and buildings, including the building that had housed the Church of England congregation (the church had been confiscated by the Patriots for storing military supplies). The sound of cannon fire rang out as the British set up their three-pounder in front of the church. One cannon ball ended up lodged in a beam at the Keeler Tavern, a known gathering place for Patriots.

After sweeping the town for any remaining Patriot soldiers, the British set up camp for the night on high ground south of the village. From there, it was possible to see and send bonfire signals to the British ships in the Long Island Sound.

Results of the Battle

1977 medal commemorating the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Ridgefield – Copyright undetermined. Used with permission from Jack Sanders.

The next day, General Tryon led his troops through Wilton and into Westport, evading an attack at the Saugatuck Bridge by the troops who had regrouped under Generals Arnold and Silliman. After a final engagement at Compo Hill, the British re-embarked their ships and sailed away to New York.

The weekend invasion of western Connecticut was successful for the British in that they achieved the goal of destroying the Continental stores at Danbury. It failed, however, to arouse greater Loyalist sentiment and it showed that the local militias were capable of rallying and causing damage to an 1,800-man force. The British won the battle, but it was the last time the British army attempted an inland invasion in Connecticut.

Sally Sanders, a Connecticut College graduate and retired newspaper editor, is vice president of the board of the Ridgefield Historical Society.

Bibliography is available upon request.