By Peter P. Hinks

Little is known about the early life of William Lanson, a remarkable black entrepreneur who contributed to New Haven’s civic growth in the first half of the 19th century. Probably born free around 1785—perhaps in Derby—Lanson along with other family members moved to New Haven about 1803. Within the short space of seven years, he had become the city’s principal wharf builder, an enterprise underwritten by his ownership of a large quarrying business.

Lanson’s Role in City’s Civic and Economic Life

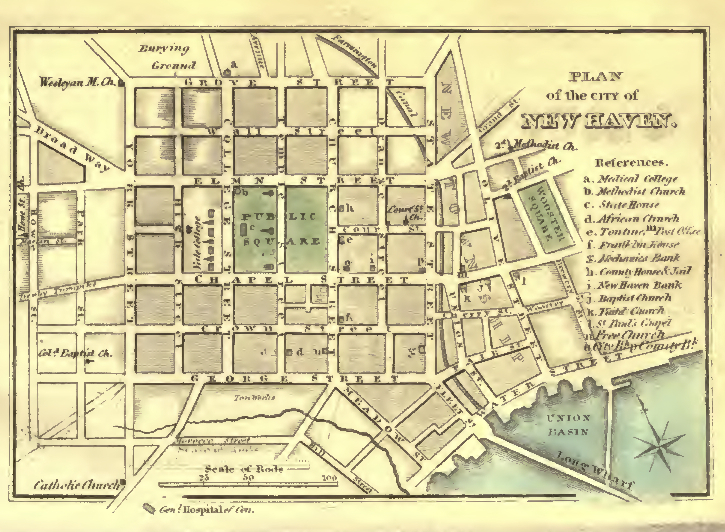

In 1810, Lanson was the only contractor able to complete the complicated 1,350-foot extension to the town’s Long Wharf. As Lanson later recalled, he had special scows (flat-bottomed transport boats) built capable of carrying 25 tons of stone at a time, stone which he and his laborers quarried from the Blue Mountain in nearby East Haven. The huge stones were loaded on to the scows on the river from a wharf carefully designed by Lanson to accommodate their great weight. Working relentlessly, even on “the darkest nights,” Lanson finished this vital civic project.

Soon afterwards, Lanson established one of the leading hostelries in New Haven on Chapel Street. With credit widely extended by the merchants, Congregationalists, and Federalists who formed the city’s old white elite, he also purchased substantial acreage and houses in New Haven’s largely undeveloped New Township in the 1810s and ‘20s. Many blacks then settled in the area, where they mixed and mingled amicably with whites who lived there, visited or just passed through.

Ad for William Lanson’s stable, Connecticut Herald, June 22, 1819

At a time many assume held few opportunities for African Americans, Lanson reaped a bounty. In an 1811 report on the history and current state of New Haven, Yale’s Reverend Timothy Dwight praised the wharfing work of William and his brothers for the “honourable proof of the character which they sustain, both for capacity, and integrity, in the view of respectable men.” Through his enterprise, Lanson had “become a good member of society” and Dwight hoped Lanson’s influence would uplift his racial brethren, many of whom had only recently come out of slavery.

By 1825, Lanson was contracted to build the retaining wall for the harbor basin into which the boats traversing the newly planned Farmington Canal would empty. In all his enterprises, he employed upwards of 30 men. At the same time, he helped found the African United Ecclesiastical Society and the African Improvement Society “for the improvement of the moral, intellectual, and religious condition of the African population of this city.” Lanson was estimably embedded in the civic and economic life of New Haven.

Expansion and Immigration Bring Rising Racial Antagonism

The pace of change accelerated in New Haven in the 1820s. After 1825, the city began to develop the New Township lands (centered around modern-day Wooster Square), and this placed unprecedented pressures upon the black neighborhood there. Residences for the affluent were erected along with a host of manufacturing shops of diverse sizes—the largest was the swelling carriage-works of James Brewster—whose exclusively white employees required housing near their workplace. Construction of the Farmington Canal led to a dramatic influx of poor and Catholic Irish laborers into the town. Hundreds of other laborers and mariners followed as well.

By the 1820s, more whites condemned blacks for lacking industry, temperance, and moral continence and for causing the new social problems accompanying the city’s growth. The flourishing of the local American Colonization Society, which called for the removal of the nation’s free blacks to Africa, helped nurture these new racial antipathies among whites. Also, the old elite who had upheld and contracted with Lanson had lost their pre-eminence and acquired some new suspicions of their own about black character. In 1827, for example, a vocal white resident could boldly proclaim in a local newspaper: “Is not the residence of coloured people considered a calamity by our white people, universally?” Anyone offering employment or assistance to them was pronounced “guilty of injustice towards white men, who have an exclusive right to be employed.”

Changed Circumstances Dim Lanson’s Prospects

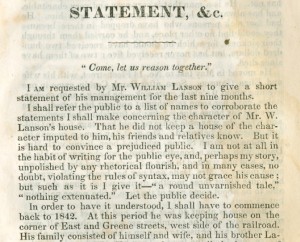

Despite Lanson’s ongoing economic success, popular sources aggressively recast him as a purveyor of vice and disorder to black and white alike in the New Township and called for the neighborhood’s extirpation. Yet, as in 1815 when he petitioned the General Assembly to protest the state’s 1814 disfranchisement of African Americans, Lanson eloquently vocalized his opposition to these characterizations and their troubling implications. He had two lengthy articles printed in the local Columbian Register, lauding the residents of his neighborhood as largely “smart and industrious people of color.” He unabashedly proclaimed the essential goodness of African Americans and the great capacity of white and black to interact successfully at work, at governance, and at play.

Isaiah Lanson’s Statement and Inquiry: Concerning the Trial of William Lanson, Before the New Haven County Court, November Session, 1845

But rising white prejudices won the day. By 1830, Lanson had moved from the Wooster Square area and in July opened a new grand “Boarding-House for the people of color” in a then-isolated corner of northeastern New Township. He called the facility the Liberian Hotel, re-located his hostelry there and planned to have sailboats for oystering as well. He also expected to continue his wharf building from the site. But Lanson’s economic and social trajectory bent downward after 1830. Encountering economic and family reversals, mounting debts, problems with his health and that of his wife, and hounded by municipal authorities intent on discovering his connection to illegal activities, Lanson lost his properties and tumbled into poverty. Upon his passing in May 1851, one obituary recalled him as “a very enterprising negro…endowed by nature with more than a common mind.” Yet, while economic, political, and demographic expansion brought numerous benefits to white New Haven after 1820, Lanson’s fate reveals just how problematic that expansion proved to be for the city’s blacks. Indeed, the city’s growth often constricted their emerging but fragile freedom more than it enhanced it.

Peter P. Hinks is a historian who has researched and written extensively on slavery and black freedom in Connecticut and the American North.