Spring training baseball is a tradition in the United States unlike any other. Every February and March major league clubs send their players to warm, sunny locations in Florida and Arizona to hone their skills, stretch their muscles, and shake off the winter. Immediately behind the players, follow the baseball fans, who revel in the opportunity to see their heroes in more personal and informal training facilities ideally suited for laying out picnic blankets and welcoming the arrival of spring. During the Second World War, however, travel restrictions severely limited the distances baseball teams traveled to begin their training, and many teams needed to find training facilities closer to their home stadiums. For the National League’s Boston Braves, this meant training in Wallingford.

Boston Braves Select Choate School as Training Grounds

In 1943, Bob Quinn, president of the Boston Braves, arrived to evaluate the baseball facilities at the prestigious Choate School in Wallingford. He met with the school’s headmaster, Reverend George C. St. John, and negotiated a deal that provided the Braves with use of the school’s enormous indoor batting cage and three outdoor baseball diamonds. In return for lending out his facilities, St. John received a promise of regular instruction from Braves’ players and coaches for his varsity baseball team.

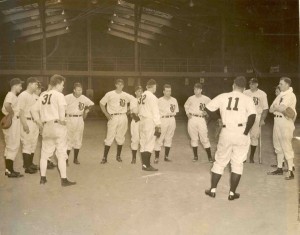

Boston Braves using The Choate School’s Winter Ex for spring training in 1943 – Photograph courtesy of Choate Rosemary Hall Archives

Under legendary manager Casey Stengel, the Braves arrived at Choate on March 22. The school housed the players in a couple of on-campus buildings and allowed them access to the fields from 9:00 am until 2:30 pm. At 2:30, the Choate players began their practices.

In the spring of 1944, the Braves returned to Choate once again. With so many major league players serving in the armed forces both at home and overseas, spring training proved a wide-open contest between a handful of remaining major leaguers, a number of minor leaguers, and any local talent available to try out for the team. That year, local residents like Bob Kobrin of Meriden showed up at camp looking for a shot at the major leagues, as did any number of players from the Braves’ minor league affiliate in Hartford.

Exhibition games proved difficult to schedule, as the cold New England weather kept most of the practices indoors and resulted in numerous game cancellations. The Braves did manage to get in some games, however, with a number of local ball clubs, including a collegiate team from nearby Yale University. The Braves donated all of the revenue they generated while in Wallingford to the Red Cross war effort.

After the war and the lifting of travel restrictions in the US, baseball readily returned to the sunbelt for its annual spring training rituals. While holding spring training in Wallingford proved less than ideal, it did allow the Braves to prepare for the season while still respecting the wishes of Major League Baseball to limit baseball travel. Reverend St. John felt like he did his part as well, helping the game of professional baseball survive during one of the most challenging periods in its history.