By Steve Thornton

Me and a man was workin’ side by side

This is what it meant

They was payin’ him a dollar an hour

And they was payin’ me fifty cent

They said, “If you was white, should be all right

If you was brown, could stick around,

But if you black, oh brother, get back, get back, get back”

–Big Bill Broonzy, “Black, Brown, and White”

A Racial Divide Among Hartford Workers

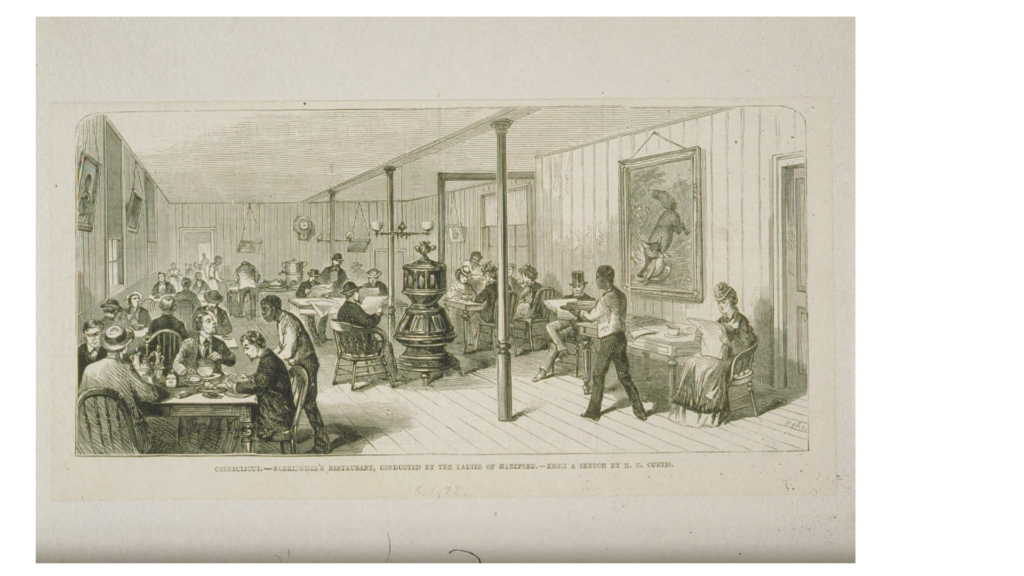

In the early 20th century, black workers in and around Hartford often earned 30-to-40 percent less than their white counterparts. While there proved precious few ways to close that gap, one effective method was to organize a trade union. The earliest labor union for African American workers in Hartford appeared in 1902 with the birth of the Colored Waiters and Cooks Local 359. The group’s guiding principles were the fight for “living wages, justice, protection and equal rights.”

The Colored Waiters and Cooks Local 359 formed on May 30, 1902, when a dozen African American waiters met at the Home Circle Club on Ford Street. There they examined the constitution and by-laws of the national Hotel and Restaurant Employees union and unanimously voted to join. “As a rule, in all cities, colored waiters are always obliged to do more work and receive small wages,” explained David D. Hilton, who lived on Garden Street and served as the local’s first president. They were also “subjected to many other unpleasant circumstances because of their color.”

Exterior of the Capewell Horse Nail Company, 1910 – Connecticut Historical Society

In Hartford there already existed a local union for white waiters, but there was no operating principle of “one big union” to form a united front for all races and provide the strength needed to effectively compete with powerful bosses. Instead, Hartford had 41 different unions for 9,000 workers in the city. This included two electricians’ unions, two cigar workers’ unions, two metal mechanics unions, and three different unions at the Capewell Horse Nail factory on Charter Oak Avenue. Such a scattered and dysfunctional setup meant cooperation between craft workers was nearly impossible, especially when they had a common employer. With unions divided by job skill and race, the workers’ ability to improve their lives proved severely limited.

During their first year of operation, Hartford waiter John Fuller and his comrades must have felt optimistic, however. They announced that “the membership roll grows larger each meeting, and everything points favorably to Local 359 being one of the best in its kind in New England. Perfect harmony prevails.” When the national hotel union met in Rochester, New York, for its twelfth annual convention in 1904, Local 359 sent two delegates. The establishment of the union “brought about the recognition of the colored waiters by the white waiters and more unity among themselves,” members claimed. The waiters also reported that black members of different trade unions began to attend their meetings: “It is a general feeling that such an organization is a long-felt want supplied for many reasons.”

Local 359 in a National Context

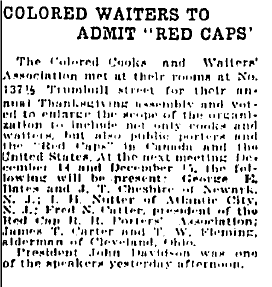

In 1918, Hartford’s Local 359 hosted a national convention of Colored Waiters and Cooks unions, including locals from Ohio and New Jersey. At the two-day event it was agreed to enlarge

Newspaper article announcing the admittance of railroad porters to Local 359. The Hartford Courant, November 29, 1918.

their base by welcoming Red Caps (the nickname for railroad porters working in the United States And Canada) into their ranks. This particular decision in Hartford laid the groundwork for other important milestones in the fight for labor and racial justice.

Organizing black workers into unions was controversial, however. Not long after the Hartford waiters came together, machinists in Virginia voted to leave their federation of unions when it admitted all-black locals. Although the legendary Knights of Labor had, in its heyday, actively recruited African Americans, they were the only national union to do so until the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) made multi-racial organizing a central tenet. It would take another thirty years before the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) began to break down the color barrier once and for all.

Civil rights and labor leader A. Philip Randolph led the organizing campaign in 1925 to unionize the Pullman railroad company into the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), the first all-black union recognized by the conservative American Federation of Labor (AFL). E. D. Nixon and his secretary, Rosa Parks, who both worked for the BSCP in Montgomery, Alabama, went on to play pivotal roles in the 1955 bus boycott that desegregated public transportation. This campaign, in turn, launched Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to nationwide prominence.

Steve Thornton has been a labor union organizer for 35 years and writes on the history of working people on the ShoeLeatherHistoryProject.com