By Eric Hintz for the National Museum of American History’s blog, O Say Can You See

Take four technologies from the National Museum of American History’s collections—a revolver, a sewing machine, a bicycle, and an early-model electric automobile. A quiz: What do these four very different technologies have in common?

Answer: all of them were made in the city of Hartford, Connecticut, around 1860 to 1905. But what really unites these very different products is the method by which they were manufactured. As the Industrial Revolution unfolded during the late 19th century, these four items were among the very first mass-produced products to appear in the United States. The precision fabrication techniques introduced and developed in Hartford drew manufacturers of all kinds of products—from guns to cars—and made the city a hotbed of innovation in the latter half of the 19th century.

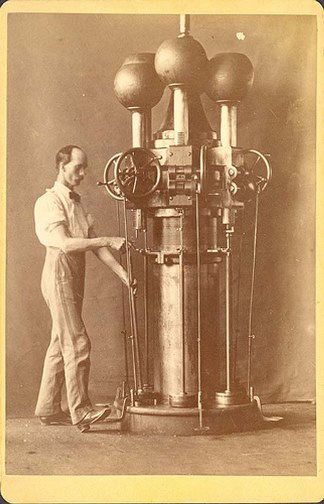

Colt machinist with a barrel-rifling machine, a specialized machine tool invented by superintendent Elisha Root, 1860s – Connecticut State Library, Colt’s Patent Fire Arms Manufacturing Company

In traditional artisanal practice, a single, highly skilled craftsman would make and assemble every part of a finished product; for example, a gunsmith would make every part of a musket, “lock, stock, and barrel.” Each of the metal assemblies—the lock, the trigger, the barrel—had to be hand-filed so that they fit together properly. Thus, each musket was unique and made to order, so production volume was low and the unit cost of each gun was high. This had certain military disadvantages. First, the slow pace of production made it difficult for the United States to maintain a steady supply of arms following the Revolutionary War and during the War of 1812. Plus, if an artisan-produced musket or revolver failed on the battlefield, the army would need a field blacksmith to repair it, since each gun was unique. Theoretically, if identical copies of a master gun design could be produced with identical, interchangeable parts, a broken lock or trigger could be repaired quickly by simply changing out the part. Thus, in the first decades of the 19th century, the Army Ordnance Board began experimenting with new manufacturing techniques at the federal armories in Springfield, Massachusetts, and Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in an attempt to achieve interchangeability. They also wrote interchangeability into the requirements for all new gun orders when they contracted with suppliers.

Enter Hartford native Samuel Colt. Colt’s patented revolver was an important invention, but his truly groundbreaking innovation was the perfection of a manufacturing process that enabled production of 10,000 identical copies of that revolver. Colt and his workers developed precise molds for forging the basic metal pieces and specialized lathes, drill presses, and milling machines to grind those metal blanks into the finished components. They also used jigs and bearing points to secure the blank pieces on the cutting machines and precise inspection gauges and calipers to ensure that the finished pieces conformed to exact specifications. These specialized machine tools—machines to make other machines—eliminated the variability introduced by hand forging and filing. Thus, by employing the division of labor, specialized machine tools, and precise quality-control standards, Colt and his engineers were among the first manufacturers to achieve interchangeable parts on a mass scale.

Columbia Light Roadster, 1886, catalog no. 307,217 – National Museum of American History

Columbia electric automobile, 1904, catalog no. 310,575 – National Museum of American History

The superintendent at Samuel Colt’s Hartford armory, the first manufacturing plant to achieve interchangeable parts on a mass scale, was Elisha Root. He was widely regarded as the finest mechanic in New England and the success of the armory attracted skilled machinists from all over the Northeast. As Root shared his expertise with the staff, Colt’s armory became known as a “college of mechanics.” These ambitious mechanics learned how to build and operate Colt’s specialized machine tools and mastered the various aspects of his manufacturing process. As they gained in knowledge, they often left Colt to apply the techniques in other industries or to start their own firms. They quickly found that the use of specialized machine tools, jigs, and inspection gauges had general applicability in any industry that required the precision forging, stamping, and milling of metal parts. Historian Nathan Rosenberg has described this phenomenon as a process of technological convergence, in which the skills and techniques learned in a given context or industry are transferred and applied for uses in other industries which seem different on the surface, but actually present similar mechanical problems. In other words, once you understood the general techniques, forging and milling a revolver’s trigger was not so different from forging and milling a sewing machine’s bobbin; once you understood how to stamp press a bicycle’s sprocket it was relatively easy to stamp press the gears for an automobile’s transmission. As Samuel Colt himself explained it more simply in 1854, “there is nothing that cannot be produced by machinery.”

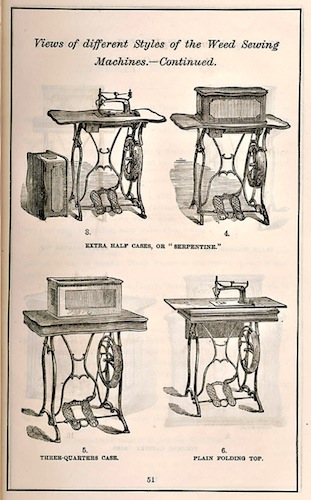

The ambitious mechanics who originally trained at Colt’s armory were the mechanism for transferring the tools and techniques of precision manufacturing across Hartford’s burgeoning industries. It was a tight-knit community, filled with overlapping relationships. For example, a former Colt machinist named George Fairfield left the firm to become superintendent and later president of Hartford’s Weed Sewing Machine Company. In 1878, with sewing-machine sales slumping, Fairfield agreed to a contract in which Weed would manufacture 50 “Columbia”-brand bicycles for Colonel Albert Pope. As bicycles boomed, Pope gained control of Weed in 1881, and shut it down altogether in 1890, as Columbia produced thousands of bicycles and, later, automobiles.

Eric Hintz is a historian with the Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation at the National Museum of American History. This column originally appeared in Prototype, the Lemelson Center’s newsletter, and is based on research done for an upcoming exhibition, Places of Invention.