By Jennifer Wilkosz

Outside the Connecticut State Capitol building in Hartford there is a monument of a young boy who represents the prisoners retained at the Andersonville Prison in Georgia during the Civil War. The prison offered incredibly harsh conditions and three of the members of the Andersonville Boy monument committee survived and understood the horrors that the incarcerated inmates faced. The prison had a 29-percent death rate, the highest of any prison during this time, and the committee wanted to ensure that no one forgot the horrors that these men endured.

Andersonville Military Prison Boy replica at the state capitol in Hartford, CT – Courtesy of Stacey Renee

Conditions at Andersonville Prison

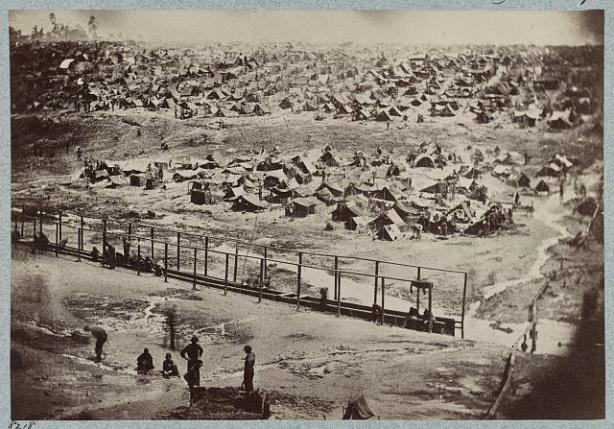

According to the National Park Service brochure “Andersonville,” the official name of Andersonville Prison was Fort Sumter. It was established in early 1864 and liberated in 1865, after only 14 months. The site of the prison was intended for about 10,000 prisoners, but at times it held more than 33,000. In its 14 months of operation, over 13,000 prisoners died there. The overcrowding created a number of problems, from lack of food and shelter to the spreading of diseases. Union Chaplain Henry S. White’s letters from Andersonville (included in Prison Life Among the Rebels) declared, “From forty to eighty men were dying each day, and the mortality afterward increased to as high as nearly two hundred per day.” Mortality on this level scarred the inhabitants of the prison and made the name Andersonville notorious. After Andersonville was liberated, people worked on identifying the bodies of those who were buried in mass graves. It was a difficult task considering that survivors were hard to identify in their malnourished states. In 1890, the Grand Army of the Republic purchased the land and it was on its way to becoming a national park.

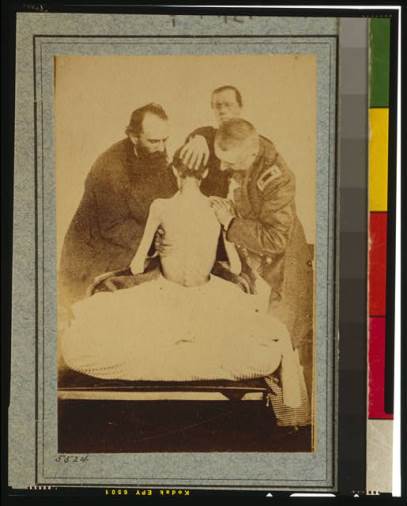

Henry Wirz, the commandant of the prison, became the focus of the public’s ire after the war ended. He was arrested and tried for “murder in violation of the laws of war,” according to the National Park Service. Wirz personally committed 13 murders at the prison, killing prisoners for breaking camp rules. As the Hartford Courant reported on July 24, 1865, “The country will be gratified to learn that Capt. Henry Wirz . . . is shortly to be put upon his trial for the cruelty and barbarity practiced by him upon our prisoners confined at that place.” He was convicted and executed for his crimes. Many believe that this was in order to provide a scapegoat, as the northern states were horrified by the condition of the survivors and the number who died at Andersonville. The people wanted someone to hold accountable and they found that in Wirz. He was the only person executed for war crimes during the Civil War.

An Andersonville Prison survivor recovering in a hospital, ca. 1864 – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Andersonville was not the only Civil War prison that had a high mortality rate. Fifty-six thousand men died at different prisoner of war camps during the Civil War. Lack of food, water, and shelter, as well as a lack of understanding regarding hygiene, led to thousands of deaths in the prisons. Conditions on both sides were horrible. The lack of fresh fruits and vegetables led to outbreaks of scurvy that often became deadly. There were even several cases of prisoners hunting rats for food.

These hardships led to the formation of gangs in prison. In Andersonville, one such gang attacked people for their supplies and some members of the gang murdered fellow prisoners. They were eventually caught, tried by fellow prisoners, and executed for their crimes.

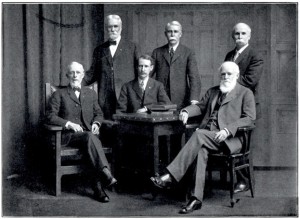

It was in these circumstances that the Connecticut 16th entered the prison in 1864. A Hartford Courant article on March 4, 1906, described the conditions at the prison: “The sufferings through the summer and fall of 1864 were indescribable. The death roll will alone indicate the story.” The article lists the 85 members of the Connecticut 16th who died at Andersonville Prison. While several other Connecticut regiments were imprisoned there, including the 21st and the 7th, the 16th had the largest number of fatalities. Surviving members of the 16th wanted to commemorate those lost at Andersonville. George Q. Whitney, George E. Denison, and Norman L. Hope were all survivors of Andersonville from the Connecticut 16th who served on the commission in charge of erecting a monument to the Connecticut soldiers who perished at Andersonville. Other members included Frank W. Cheney, Frederick W. Wakefield, and Theron Upson. Cheney and Upson were also veterans of the Civil War, though they had not been incarcerated at Andersonville.

A Monument in the Making

The Connecticut General Assembly appropriated $6,000 in 1906 for a monument to be placed at the Andersonville Prison site. The committee wanted the statue to represent all the men who had been held captive at Andersonville Prison and the one aspect all those men agreed upon commemorating was their lost youth. The committee members were 40 years older and looking back at their time spent as soldiers in the Civil War and this helped to choose the design for the statue, when they picked Bela Lyon Pratt’s design on July 11, 1906. It seemed as though Pratt discounted the price of his statue. The Hartford Courant noted in “For Prisoners at Andersonville” on April 2, 1907, that “Mr. Pratt, the sculptor, is a son of Connecticut, being a native of Norwich, and he has made his price very low because of his loving interest in the work. Recently he received $10,000 for a similar statue.” Pratt’s statue kept in-concert the idea of youth; when compared to other Civil War soldier statues, the most notable difference was that the Andersonville Military Prisoner Boy had no beard and no rifle.

A photo of the Commission appointed to erect a statue honoring Connecticut soldiers who died at Andersonville Prison. Standing from left to right: George E. Denison, Norman L. Hope, George Q. Whitney. Seated from left to right: Theron Upson, Frederick W. Wakefield, Frank W. Cheney. From the book, Dedication of the Monument at Andersonville, Georgia, October 23, 1907, in Memory of the Men of Connecticut Who Suffered in Southern Military Prisons, 1861-1865

The commission traveled to Georgia to select a place to put the statue. On arrival, they chose an area where the statue would be framed by an amphitheater of trees, trusting it to be a peaceful location to honor their comrades. The dedication of the Andersonville Prison Boy took place on October 23, 1907. The statue stood eight feet tall with an eight-foot pedestal and had an inscription that read, “In Memory of the men of Connecticut who suffered in Southern military prisons, 1861-1865.” In preparation for the dedication, the Grand Army of the Republic, in conjunction with the State of Connecticut, sent out invitations to the almost two hundred living survivors of Andersonville Prison. One hundred and three traveled to Georgia for the dedication ceremony. About three hundred Connecticut men lie buried in the cemetery and, after the dedication ceremony, many of the visitors went around the prison cemetery to find their fallen comrades’ gravestones. Dedication of the Monumentat Andersonville, Georgia quotes Colonel Frank Cheney’s address at the dedication:

[O]ur Soldier Boy of Andersonville, the ideal young soldier, as he stood for all that is noble and loyal and enduring when he offered himself and his life, if need be, for our loved country. We leave him here, feeling that he is a son or brother, loved or lost in the service of his country, and that his is now with our comrades at rest.

Cheney wanted the people of Connecticut never to forget those who had suffered within the prison so he arranged to buy a replica of the statue. He hoped the statue would live at the state capitol, but he had only purchased a statue and not its pedestal. Comptroller T. D. Bradstreet wanted the state to purchase the pedestal, and the state passed a bill appropriating $2,000 for the pedestal and chose a place outside the capitol building to erect the statue. The statue was dedicated on September 17, 1909, and George Q. Whitney, a survivor of Andersonville Prison and a member of the original commission, spoke at the dedication. Although Cheney did not serve time at Andersonville Prison, he did feel a strong connection to the monument. When asked permission of the state of Connecticut to use the same statue for Massachusetts, Cheney demurred and simply said, “the boy belongs to Connecticut.”

Some former Connecticut prisoners who were present at the dedication of the Andersonville Military Prisoner Boy. From the book Dedication of the Monument at Andersonville, Georgia, October 23, 1907, in Memory of the Men of Connecticut Who Suffered in Southern Military Prisons, 1861-1865

Jennifer Wilkosz is a Berlin High School social studies teacher who is currently finishing her second master’s degree through the James Madison Fellowship, a national fellowship awarded to one social studies teacher per state per year.

This article was published as part of a semester-long graduate student project at Central Connecticut State University that examined Civil War monuments and their histories in and around the State Capitol in Hartford, Connecticut.

<< Previous – Home – Next >>