By Austin Sullivan

In front of the state capitol lies a monument that holds roots in our nation’s bloodiest conflict. It is simple yet powerful; dedicated to the men of the First Connecticut Heavy Artillery Regiment. As taken from the Official Souvenir and Program released at its unveiling; it was the expressed wishes of the veterans for the monument to memorialize the fallen, and to teach future generations to answer their country’s call when the time comes.

The First Connecticut Heavy Artillery Regiment in Battle

The 1st Connecticut was created from the former Fourth Connecticut Volunteer Infantry on January 2, 1861, in Washington, DC. A typical regiment was divided into ten companies, with one hundred soldiers apiece. Trained in the use of artillery, the 1st Connecticut helped defend the Union capital until April of 1862. From there, they became attached to the Army of the Potomac for General McClellan’s Peninsula campaign. The regiment was involved in siege operations around Yorktown from April 12th to May 4th. Following the siege, the First became involved in what was later known as the Seven Days Battle, facing off against Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. The Heavies, as Bruce Catton called Heavy Artillery Regiments in A Stillness at Appomattox, fought at Gaines Mill on June 27th and Malvern Hill on July 1st. Following McClellan’s retreat from the peninsula, the Heavies again took up arms in Washington’s defense.

Companies B and M of the regiment, however, were given a different task. The two were detached to the Army of the Potomac. From there they were involved in the disastrous Battle of Fredericksburg in mid-December, 1862. They were still in the army when Lee achieved his greatest victory at Chancellorsville in May of 1863. Both were also present to witness Lee suffer his terrible defeat at Gettysburg in July of the same year. The two companies remained in the army until January of 1864, when they rejoined the First in Washington.

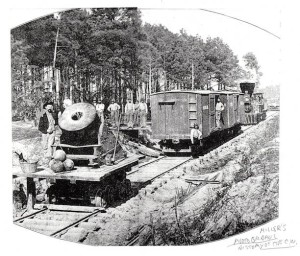

“Dictator” – The Traveling Mortar in Front of Petersburg, 1864. The mortar was unique in that it was mounted on a rail car. Photograph from Francis Trevelyan Miller’s The Photographic History of the Civil War, Vol. V, 1911.

The regiment performed garrison duty around the capital until May of 1864, when they were deployed south to Virginia. There, Major General Benjamin Butler had led the Army of the James up towards Richmond. His objective was to keep Confederate troops in the area in place. This was part of an overall strategy by Lieutenant General Ulysses Grant to bleed Lee’s army white as it fought the Army of the Potomac in the Overland Campaign. Butler, however, became trapped south of Richmond in Bermuda Hundred; an area sandwiched between the James and Appomattox rivers. The Heavies reinforced Butler on May 13, 1864. The army remained alone until Grant maneuvered south of Richmond, towards the town of Petersburg.

While small, Petersburg’s railways provided the logistics to support Richmond and its garrison. Capturing the rail hub meant the starvation of the Confederate capital. When the initial assault in taking the town failed, the army began the famous Siege of Petersburg. Still in Bermuda Hundred, the First dug what was one of the most significant systems of trenches used during the Civil War. Conditions along the lines were deplorable. The Hartford Courant said it best in its issue of September 22, 1902, when it noted that “veterans who were there are the only ones who can feel the reality and strain on courage and endurance.”

During the 11-month siege, the Heavies provided valuable artillery support to the besieging Federals. As noted in the June 5, 1896, issue of the Hartford Courant, the First fired over 63,940 rounds from various types of artillery, equivalent to 1,200 pounds of iron. The most notable of their actions involved silencing a formidable Confederate position. Known as “The Chesterfield Battery,” it was situated behind Petersburg. Well placed, it threatened the right side of the Federal lines. To deal with the threat, Butler ordered a 13-inch seacoast mortar sent to Petersburg in early July. A section of railway was located behind Federal lines, allowing the mortar to be placed on a rail car.

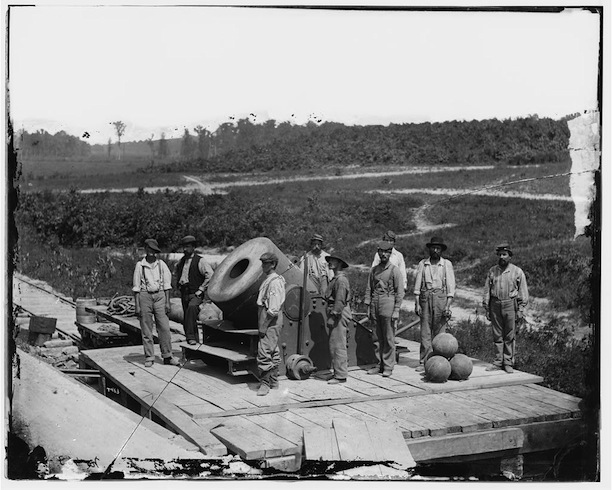

The Express during the siege of Petersburg. The First Connecticut Heavies fired 218 rounds from the Express – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Civil War photographs

Command of the weapon was given to the Heavies, manned by a section from Company G. Starting on July 8, the mortar began firing on Confederate positions. Firing from the rail car, and a fixed platform, it was essential in silencing the troublesome Chesterfield Battery. Being placed on a rail car, the mortar received a nickname, the “Petersburg Express.” The First and the Express continued their work at the end of the month, when General Ambrose Burnside launched his audacious Mine assault. The plan, to create a hole in Confederate land with a massive underground explosion, was met with abject failure. During the bloody day of July 30, the Heavies fired 19 shells from the mortar, which helped keep the Rebels from exploiting their victory.

In the months following the failed Battle of the Mine, the mortar was withdrawn to Fort Monroe, Virginia. As winter brought forth a new year, Companies B, G, and L were briefly detached to help capture Fort Fisher in North Carolina. The regiment continued supporting the siege until the town was captured on April 2nd. Following the collapse of the Confederacy, the Heavies engaged in garrison duty in Virginia until July 11th. From there, the regiment was brought back to Washington, where they became part of the garrison for a few months. The First Connecticut was officially mustered out of service on September 25, 1865. The total enrollment of officers and men during its existence came to 3,802. The casualties for the Heavies reflect the long-standing notion that more soldiers died off the battlefield than on it. Only two officers and 49 enlisted men were killed or mortally wounded, while four officers and 172 enlisted fell by disease. In total, the First Connecticut Heavy Artillery Regiment suffered 227 casualties defending the Union.

Commemorating the Heavies

Plans to commemorate the Heavies did not get underway until the early 1890s. The General Committee and Regimental Association, formed from veterans of the First, brought up the subject in 1892. The general consensus was to use the famed “Petersburg Express” for the monument. Captain Frank Miller found the mortar at Fort Monroe, where it had been left. Initially, the Captain had trouble identifying which mortar was the right one; there were two likely choices that had been built at the same time, their foundry numbers 94 and 95. However, as the Hartford Courant noted on September 22, 1902, a sergeant in the fort’s Ordinance Department recognized number 95 as the one, from a broken lug at the top of the mortar. Miller was able to bring the weapon to Bridgeport in 1896, with the help of fellow veteran and congressman, Charles Russell. There, the weapon stayed for several years.

There were problems, initially, gathering the necessary funds for the monument. In an effort to have the monument erected in his city, the mayor of Bridgeport offered to donate $25,000 (equivalent to over half a million dollars today) for the mortar to be placed in Seaside Park. The committee, however, declined the generous offer. Regimental Historian John C. Taylor explained the reasoning in a Hartford Courant editorial dated June 13, 1896. He reasoned that the Fourth Connecticut was mustered in Hartford, hence having ties to the city. The regiment also wanted the mortar on capitol grounds; in order to provide future generations with an object important to local history and one that symbolized the commitment with which Connecticut gathered men to fight for the Union. Discussion regarding where to place the mortar carried into the 20th century. Interestingly, the June 14, 1900, issue of the Hartford Courant made its first mention of the alternate nickname of the mortar, “Dictator.”

In time, enough money was raised to make the goal of the committee possible. The Official Program had the total amount of funds at $6,136.43 (close to $145,000 today). An interesting note is that the state only gave $1,000 to the fund; the rest was donated by other groups. Over a third of the fund was given by William and Morgan Bulkeley; it was a memorial to their brother Charles, who lost his life at Petersburg. The contract and $5,500 were awarded to Stephen Maslen of Hartford. Maslen was the head of a monumental works that carried his name. The mortar and its carriage were placed on a pedestal made of granite. The monument was dedicated on September 25, 1902, the anniversary of the day the regiment mustered out. While the exact number of spectators is unknown, the Hartford Courant stated that provisions were made for 2,500 people, with the probability of up to 50,000 attending. While it had taken a long time, the Heavies finally had their monument.

The Petersburg Express post-Commemoration

For a while after the commemoration, the “Petersburg Express” kept itself in the Hartford Courant. Just four years later, on Independence Day, Taylor met with J. J. Porter, a former lieutenant in the Army of Northern Virginia. In November 1910, an article from the Courant talked about Archibald G. McIlwaine Jr., the president of the Oriental Insurance Company. He was Virginia-born and had survived the Siege of Petersburg with his mother. The mortar again became public focus at the start of the Great Depression. There was a letter to the editor that called for the weapon to be dumped in the Hog River, with a rebuttal a week later from the daughter of a First Connecticut veteran. It was part of a larger dispute regarding a captured German cannon placed in the city, but there was nothing more on the matter of the mortar.

The next mention of the “Petersburg Express” held a more hopeful tone. In 1935, the Department of the Interior constructed a concrete replica of the mortar, in the exact spot it had been during the siege. The replica lasted until 1969, when it was destroyed. This was intentional, as the Petersburg National Battlefield Park received an actual mortar through a trade with Fort Sumter.

Former Confederate Captain Carter Bishop stands by the concrete replica of the famed mortar at Petersburg, Virginia, in 1935. Photograph from “Construction of Replica Petersburg Express” by Manning C. Voorhis – National Park Service

Beginning in the 1950s, there was considerable doubt that the mortar was the actual “Petersburg Express.” This first came to the attention of the Hartford Courant in 1958. Their September 28th issue ran an article which referred to a mortar in Oneonta, New York. The local newspaper, The Star, claimed that the mortar there bore a greater similarity to the “Express.” Using “A Photographic History of the Civil War,” the newspaper compared photographs of the mortar during the siege with current ones from Hartford. They concluded that the two were not the same, citing differing positions of hooks on the mortars and that the Hartford mortar lacked an eye for hoisting. The article concluded, however, that the data was inconclusive; there was a probability that the photos were altered post-war. Following this issue, the Courant ran an article which countered the New York claim. The claim came from a Manchester resident, who had a grandfather in the First Connecticut. His grandfather left behind relics of the regiment’s reunions, which included photographs of the mortar. When compared, the Hartford mortar and the “Petersburg Express” matched.

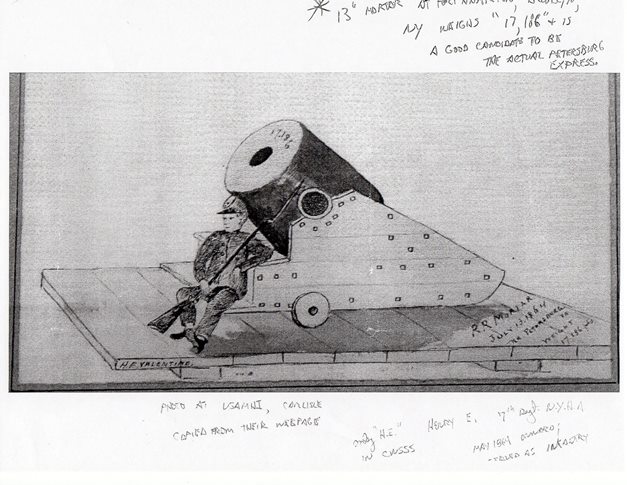

Those claims have still have not gone away. It is the opinion of Dean Nelson, Administrator at The Museum of Connecticut History, that the mortar on capitol grounds is not the “Express.” His main argument involves the weight of the mortar. During the Civil War, most artillery pieces had their weight marked on the muzzle. This process is corroborated by the work of Historian John L. Morris, who investigated the identity of the mortar in the mid-1980s. Both base the weight of the “Petersburg Express” from a sketch drawn during the siege. It was drawn by an H. E. Valentine of the Seventh New York Heavy Artillery. Among the words etched on the lower right corner is “RR mortar. July 13, 1864. 17, 186 pds.” The weight marked on the muzzle is also the same. This is contrasted by recent photos of the Hartford monument by Nelson. The weight on that muzzle is 17,197 pounds. In his research, Morris theorized the mortar at Hartford, while not at Petersburg, served with the Heavies during the siege of Yorktown. He drew this from the fact that the First was supplied with multiple mortars from the same source, Fort Monroe.

Sketch of the Petersburg Express by H. E. Valentine of the Seventh New York Heavy Artillery Regiment. The numbers on the muzzle, 17,186, provide fuel for the controversy whether the monument is the real Petersburg Express.

As of now, the identity of the Hartford mortar still remains in doubt. The claims of the regiment and the Hartford Courant are challenged by modern historians. It is possible that Frank Miller made an error when searching for the mortar. Over 40 years elapsed between the end of the war and the erection of the monument. While the monument may not have the correct mortar, Morris argues that it is still historically significant. By the time he had conducted his research, only 26 out of 162 seacoast mortars had avoided being scrapped. The Hartford piece still symbolizes the courage and sacrifice made by the First Connecticut in defense of the Union.

Austin Sullivan is a graduate student at Central Connecticut State University; he is a native of Stafford Springs, Connecticut, and holds a bachelor of arts degree in social sciences from Lyndon State College.

This article was published as part of a semester-long graduate student project at Central Connecticut State University that examined Civil War monuments and their histories in and around the State Capitol in Hartford, Connecticut.

<< Previous – Home – Next >>