By Nancy Finlay

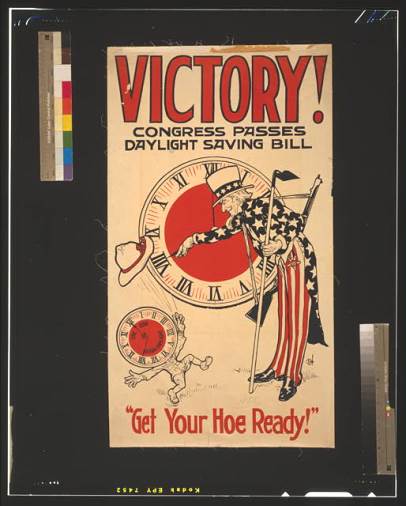

Poster “Victory! Congress Passes Daylight Saving Bill”, showing Uncle Sam turning a clock to Daylight Saving Time, 1918 – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

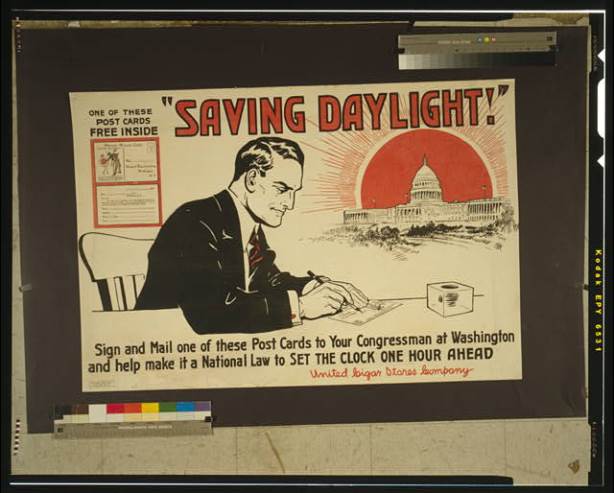

The idea of setting clocks ahead so that everyone has “an extra hour of daylight” was first suggested by Benjamin Franklin, way back in 1784. The idea was slow to catch on, perhaps because in agricultural communities—and most communities in America at that time were agricultural communities—clock time had little meaning. Farmers regulated their lives by the rising and setting of the sun. European nations finally introduced Daylight Saving during World War I as an energy saving measure. President Wilson urged its adoption by the United States and Congress finally endorsed it in 1918. Clocks were to be set ahead one hour the last Sunday in April and turned back one hour the last Sunday in October. In both Europe and the United States, Daylight Saving Time proved controversial, and nowhere was it more controversial than in Connecticut, the land of steady habits.

Standard Time

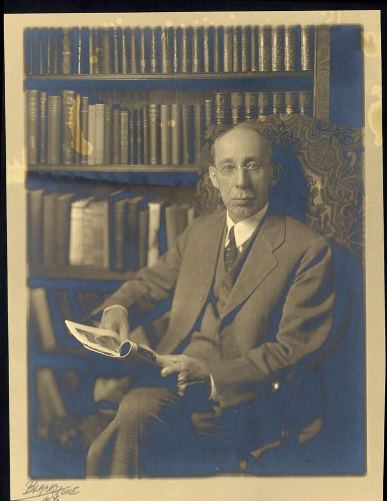

Standard Time is a relatively new concept. It was only in 1883 that the North American continent became officially divided into time zones. Sun time is a continuum, changing as the earth turns and the path of the sun progresses across the land. Time zones are an arbitrary construct, and originated primarily for use with railroads, as a means of facilitating clear and consistent schedules. By 1918, however, time zones became widely accepted and some people argued that setting the clocks ahead went “against nature.” In a letter to the Hartford Courant, inventor Curtis Veeder pointed out that in Connecticut, Eastern Standard Time, based on the actual sun time in New York City, was roughly half an hour off, and therefore adopting Daylight Saving Time did not make all that much difference in the clocks’ accuracy.

Inventor Curtis H. Veeder in the library of his home at One Elizabeth Street, Hartford. The building now houses The Connecticut Historical Society, ca. 1930 – Connecticut Historical Society

Daylight Saving proved popular with some and wildly unpopular with others. In general, city dwellers and factory workers appreciated the extra hour of daylight in the evening that allowed them to work in their Victory Gardens and to attend afternoon ball games. In the country, farmers complained that Daylight Saving actually cost them an hour of daylight, making farm workers an hour late getting to the fields. Connecticut patriotically supported Daylight Saving during the war, but once the war was over, resisted attempts to continue the practice. Tobacco farmers were among the most vocal opponents of the measure.

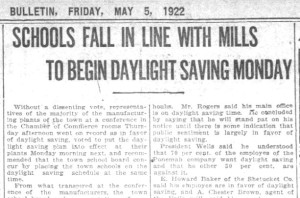

For a few years, the Connecticut legislature did not take an official stand, allowing individual towns and businesses to decide whether or not to adopt Daylight Saving. The resulting confusion kept the issue very much alive in the public consciousness. Mothers complained that Daylight Saving upset their children, who did not understand why at the end of April they suddenly had to get up in the dark and go to bed by daylight rather than the other way around. One father in Norwich refused to adopt Daylight Saving Time even though the town did, and continued to send his children to school at the usual hour, making them one hour late every day.

Connecticut Outlaws Daylight Saving Time

Then in 1923, Connecticut passed a law officially maintaining Standard Time all year round and prohibiting the “willful public display of daylight saving time.” Eastern Standard Time was to remain the official time throughout the state. This did very little to simplify matters, since many businesses simply ignored the rule. Between the end of April and the end of October, the clocks in church steeples and courthouse cupolas and on the sidewalks of Hartford might show Eastern Standard Time, but the moment you stepped through a door into a bank, store, or restaurant, the clocks all displayed Daylight Saving Time.

Detail from Norwich Bulletin article, May 5, 1922 – Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers

Some businesses, like Travelers Insurance Company, observed Standard Time but required workers to report to work an hour early. Federal offices all observed Daylight Saving and so, by the end of the decade, did all of the neighboring states. The law was challenged by a Hartford jeweler, who faced arrest for setting the clock in front of his jewelry store ahead one hour. The case made it all the way to the Connecticut Supreme Court, which ruled that the law was, in fact, constitutional. It was clearly inconvenient, however, and in the 1930s legislators quietly repealed it.

That did not end the debate over Daylight Saving Time, however. More than 90 years later, the controversy still continues, and Daylight Saving Time has even been extended, so that it now runs from March through November. People still argue that Daylight Saving saves money on energy bills and studies seem to show that it actually does. There are fewer farm workers to complain about losing an hour of daylight in the morning, but it is still more popular with those people who like to stay up late than with those who like to get up early. But at least now everyone changes the clock at the same time in the spring and fall, and all year round everyone in Connecticut agrees what time it is.

Nancy Finlay grew up in Manchester, Connecticut. She has a BA from Smith College and an MFA and PhD from Princeton University. From 1998 to 2015, she was Curator of Graphics at the Connecticut Historical Society.